The Merlot vines on the right, with red leaves, are infected with grape leafroll disease. Notice the smaller clusters in the infected vine compared to a healthy vine on the left.

(Courtesy Washington State University)

Viral diseases affect vine health, fruit yield, and quality and lead to poor quality wines. Thus, the industry must instill concerted and collaborative approaches among the stakeholders, researchers, and regulatory agencies to thwart the increasing threat of viral diseases in vineyards. This is of paramount importance for advancing sustainable growth of an industry that continues to make significant contributions to the state economy.

One aspect of viral diseases that remains unresolved is the effect that they can have on the profitability and sustainability of Washington’s vineyards.

To address this question, a project was funded by the Washington State Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program to determine the economic impacts of viral diseases on growers’ pocketbooks.

Merlot wine made from grape leafroll-infected fruit was lighter colored than wine from uninfected Merlot grapes of the same block. (Courtesy Chris Beaver/WSU)

Washington State University scientists teamed up with agricultural economists, Trent Ball and Ray Folwell of Agri-Business Consultants, to estimate the operating returns lost by a grower due to viral diseases. The team has initially focused on the economic impact of grapevine leafroll disease, by far the most insidious viral disease in Washington vineyards.

The study used yield and fruit quality data obtained from previous WSU research that studied a commercial Merlot vineyard from 2009 through 2012. In that trial, yield was reduced from 12 percent to 28 percent during the four years.

Further, Brix, which is a measure of sugar in the fruit, dropped below 23.5°, the desired contract minimum in seasons with below average growing degree-days (heat accumulation). Brix was measured at 23.1° and 22.5° in 2010 and 2011, respectively. There can be as much as a 2 percent price reduction penalty for each 0.1° Brix reduction below the 23.5° minimum.

Yield and quality losses

Data from the Merlot study were used to answer two questions:

1. How much is lost (in terms of operating returns) when fruit yield is reduced by 10 percent, 20 percent, or 30 percent?

2. How much is lost (in terms of operating returns) from a combination of reduced fruit yield and price penalty imposed by wineries when grapes have less than expected sugar levels?

A base-line scenario for a Merlot vineyard was created using an average annual yield of 4.5 tons per acre and a three-year average price of $1,127 per ton. The associated variable costs were calculated using the Northwest Grape Costs of Production Calculator using 2014 prices and production practices for a vineyard in full production. Industry stakeholders participated in discussions and validation of costs estimated for grape production.

Annual operating returns (excluding fixed costs) were calculated for a Merlot vineyard that had no virus infection as the base-line scenario.

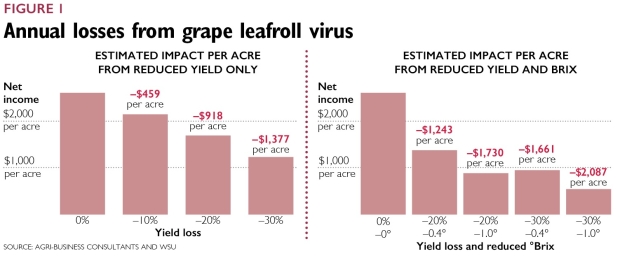

The base-line operating returns of $2,619 per acre were compared to the operating returns for vineyards managed under various virus infection scenarios of crop losses and reduction in fruit quality, especially sugars measured as Brix. (See Figure 1.) The study used two Brix reduction scenarios—a loss of 0.4° and 1.0° Brix.

Source: Agri-Business Consultants and WSU

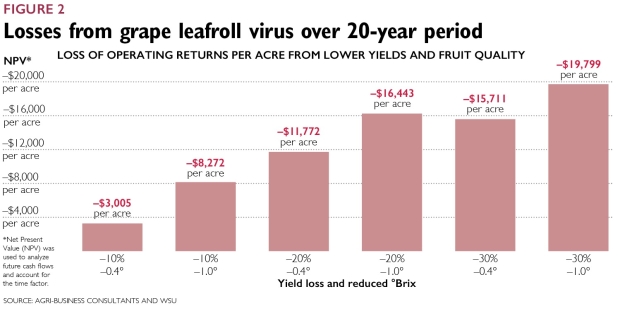

Assuming a 20-year life span for a healthy Merlot vineyard, the Net Present Value (NPV) approach was used to estimate the operating return that would be lost due to leafroll disease. (NPV is a method of analyzing future cash flows.

The overriding concept is $100 today is worth more than $100 ten years from now, because of the time value of money. NPV accounts for the time factor and brings all future cash flows to the present.) In the best case scenario, a grower experiencing 10 percent decrease in yield and 0.4° Brix decrease would lose an estimated $3,005 per acre over the 20-year span of the vineyard. The estimated loss for the worst case scenario of 30 percent yield decline and 1.0° Brix decrease was $19,800 per acre over the 20-year period. (See Figure 2.)

Source: Agri-Business Consultants and WSU

For the first time, the data generated from this project provide reliable estimates of crop losses in Merlot and science-based information on how grape leafroll disease can impact growers’ operating income in Washington vineyards. The results from this study indicated that reduction in fruit yield and quality due to leafroll infection is real, tangible, and significant. It is important to note that, even at a minimum loss of 10 percent yield, leafroll does impact a grower’s pocketbook negatively over the life of a vineyard.

Although this study is confined to one cultivar, it is likely that leafroll disease can cause substantial economic impact to other wine grape cultivars. Preliminary analysis of the economic impact of red blotch in Merlot also indicates that the disease could cause substantial losses to growers’ operating returns. The research team is currently extending these studies to determine economic impacts and financial implications of viral diseases in other wine grape cultivars.

In addition to estimating operating returns lost due to viral diseases, the team will be assessing the economic benefits of implementing control strategies such as roguing, or removing virus-infected vines, and vector control and to identify economic thresholds (when losses due to viral infections in a vineyard exceed operating returns) of viral diseases to help growers decide when to replant vines or replace infected vineyards.

A clear articulation of the financial benefits of management of viral diseases will promote rapid adoption of best management practices by growers and strengthen industry efforts in advancing clean plants for healthy vineyards. •

Disease has hidden costs

Rick Hamman of Hogue Ranches in Prosser, Washington, says the losses from grapevine leafroll disease estimated in the Washington State University study by agricultural economists are real, though they are often hidden from growers.

“These are real numbers, and they do hurt your pocketbook,” said the viticulture manager. “A lot of times, you don’t really see the numbers because you tolerate and live with the disease.”

Hamman, who helped validate grape production costs used in the economic study on leafroll disease, has firsthand experience with what he calls a “virus tax.” In the last ten years, he’s been involved with replanting eight blocks infected with leafroll and other diseases.

He says there are hidden costs involved with replanting, including demolition costs of pulling out trellis posts and wires and digging out roots that could harbor disease. Moreover, it takes three years before a replanted vineyard returns to full production.

“That’s why it’s very important to use only clean plants,” Hamman said. “And you probably need to test plant material even if it’s certified. We bought certified Chardonnay Clone 37 from a California nursery, and in the second leaf I noticed we had funny colored leaves, which I initially thought was related to potassium deficiency.”

But what really got his attention was when sugar levels in the block seemed stuck and never rose above 21° Brix, even four weeks after everything else was harvested. Eventually, leafroll disease was confirmed in the eight-acre block, but only after wood was used to propagate a second five-acre block. Both blocks had to be removed.

He believes losses from leafroll disease hit a small grower with limited acreage even harder than one who has several different blocks and can better absorb a hit to operating revenue. —by Melissa Hansen

Leave A Comment