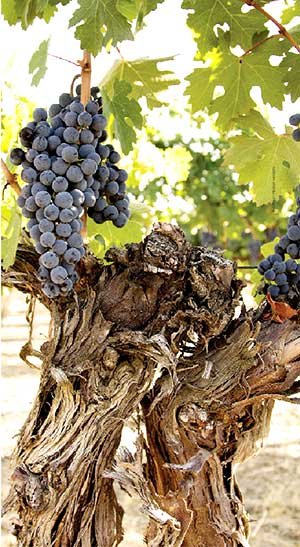

An old Cabernet Sauvignon vine at Kestrel View Estates Vineyard near Prosser.

Photo courtesy of Wine Yakima Valley

Vines planted 30 to 40 years ago are hard to find in Washington State, a relative newcomer to the wine world. Kestrel Wines of Prosser holds the distinction of owning some of the state’s oldest Chardonnay, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Malbec, with some dating back to 1972.

Kestrel Wines, owned by Helen Walker, can’t take credit for planting the vineyard—the vines were planted by pioneer Mike Wallace and sold to Kestrel in 1996. But the vineyard has stayed in production, and Kestrel uses the fruit to make several “old vine” wines.

Still-producing old vineyards can be hard to find for several reasons, says J.J. Compeau, Kestrel Wines general manager. Growers often replant old vineyards because production drops off, the variety is no longer popular, or diseases become so severe they impact fruit quality.

In the 1990s, Riesling wines lost consumer favor, and vineyards in the state were torn out and replaced with red wine grape varieties. Just recently, the white variety made a comeback with wine drinkers, and it became one of the top-selling varieties with grape nurseries.

Compeau believes there is value in keeping old vineyards in production. He says that as vines reach 18 years of age, quality goes up and the vine self-regulates its productivity. Old vines show the vineyard’s terroir or sense of place.

“Old vines, with their deep roots, express soil attributes and things like minerality,” he said, but added that as the vine self-regulates, yields are reduced.

Kestrel’s old Cabernet Sauvignon block yields around 1.2 tons per acre. For their Merlot, the average yield is two tons, and for Chardonnay, two to four tons. “That’s way below statewide averages,” Compeau said. Depending on variety and location, some young vineyards in the state can yield ten tons per acre, which is why the crop is often adjusted through thinning.

“As a winery, we can justify the reduced tonnage from old vines and put up with the low yields,” Compeau said. “But a grower would need to find a way to balance the lower productivity with higher returns.”

Wine style

Several years ago, Kestrel changed its winemaking style for their Chardonnay wines made from the block planted in 1972, some of the oldest Chardonnay in the state. “We wanted to bring out the fruit flavor and not have as much emphasis on oak flavors,” he said. “Since doing so, our old-vine Chardonnay wines have developed a cult-like following. We believe that for old vines, it’s important to let the fruit shine in the wine and not over-oak.”

Several years ago, Kestrel changed its winemaking style for their Chardonnay wines made from the block planted in 1972, some of the oldest Chardonnay in the state. “We wanted to bring out the fruit flavor and not have as much emphasis on oak flavors,” he said. “Since doing so, our old-vine Chardonnay wines have developed a cult-like following. We believe that for old vines, it’s important to let the fruit shine in the wine and not over-oak.”

Kestrel winemaker Flint Nelson agrees that the old vines produce fruit very different than young vines. Fruit from the old vines are high in tannins, have above-average acidity, and express minerality and spiciness in the wines, he said.

“Grapes grown in Yakima Valley are similar to Old World grapes,” Nelson said. “We’re not as sexy an area as some, but we have fruit qualities of elegance and balance that make our wines more like Old World wines.”

Nelson has been winemaker at Kestrel since 2004.

He graduated from Washington State University in 1991 and was one of the first recipients of WSU’s Walter Clore scholarships. Before leading Kestrel’s winemaking team, he worked under Brian Carter at Apex Cellars, and also gained winemaking experience from Paul Thomas Winery and Hogue Cellars.

He believes that because Yakima Valley is a cooler region than its neighbors Horse Heaven Hills, Wahluke Slope, and Red Mountain, growers have been forced to pay more attention to the vineyard during the growing season.

“The growers can’t slack off,” Nelson said. “They have to be on top of things to make sure that crop loads are balanced for timely ripening. They grow less tonnage per acre in Yakima Valley than elsewhere, but they also have a long hang time, which allows fruit to fully mature.”

Strengths

Several things add up to make Yakima Valley distinct among wine growing regions, he said.

Both Compeau and Nelson say one of Yakima Valley’s greatest strengths is its diverse microclimates and ability to grow a wide range of cultivars.

Syrah is especially suited to the Yakima Valley, said Nelson. “It does well in other places, too, but Yakima Valley Syrah wines have elegance and finesse.”

Kestrel planted their first Syrah vines in 1996, a decade after Mike Sauer of Red Willow Vineyard planted the first Syrah in the state.

Compeau said the Yakima Valley is one of the few regions in the state that can do so many great varieties. Well-known wineries, like DeLille Cellars in Woodinville, use almost all Yakima Valley grapes in their wines.

In the early years, wineries pondered whether to put Washington State, Columbia Valley AVA, or Yakima Valley AVA on the label. Although much of the fruit produced in Yakima Valley is blended by wineries outside the region and loses its true identity, more wineries are including Yakima Valley vineyard designations on the label, Nelson said. “That just helps more consumers learn about the area.”

Leave A Comment