While the Washington State University tree fruit endowment scored a new fire blight specialist this year, existing researchers in the Northwest and beyond updated growers on the bacterial foe at several winter meetings.

Tianna DuPont, a Washington State University tree fruit extension specialist and associate professor in Wenatchee, and Ken Johnson, an Oregon State University professor and plant pathologist based in Corvallis, both made presentations about research into methods of controlling fire blight besides straight antibiotics, which no longer qualify for organic use.

None of the alternative products and techniques offer silver bullets but can help as part of the overall process. “Yes, this is good news, but we need to be careful to use these products where they make the most sense,” DuPont said in a follow-up interview.

At the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission’s Apple Crop Protection Research Review in January, DuPont discussed integrated fire blight management. Researchers from OSU, Cornell University and Penn State University worked with her in 2018 and 2019 on materials to prevent bloom infections, management for young trees and cutting in blocks already infected.

Among the critical findings, DuPont said, was reiterating the importance of timely summer cutting.

The researchers found cutting 12 to 18 inches below the noticeable infection, into 2-year-old or older wood, significantly reduced the number of new infections popping up in other parts of the tree. Also, more aggressive cutting was not beneficial in most studies, she said.

WSU has given the 12-to-18-inch advice for years, but this recent round of trials backs it up with more data, DuPont said. In some of the trials, all the trees with no removal of infection died.

When infection points don’t allow for cutting back 12 inches, leaving a 5-inch-long stub significantly reduced the number of cankers on structural wood, compared to shorter stubs or flush cuts, in half of the case studies.

As for protecting young trees, removing flowers worked best when followed by three weekly applications of copper. Using Actigard three days before infection on young, replacement trees in a mature, infected block reduced trunk cankers.

On the new materials front, DuPont and her colleagues found alum, short for nonlabeled experimental potassium aluminum sulfate, performed well in seven of eight trials, while thyme and cinnamon essential oils provided moderate control. Thyme oil, in particular, worked well as part of an organic program following Blossom Protect.

Alum and essential oils also work on pears, as does peroxide, according to DuPont’s three-year study on biopesticides. She presented findings from an ongoing trial about that in mid-February at the Pear Research Review.

Alum showed consistent positive results over six trials with an average of 64 percent control. Standard organic products, such as Blossom Protect or soluble coppers, provide around 70 percent control.

DuPont also tested new peroxide products with higher levels of peracetic acid, which disrupts cell walls, denatures proteins and leaves little residue. Those products are showing promise based on 2021 trials with three applications in which they provided comparable control to organic standards, better than earlier trials with less frequent applications, DuPont said.

Commercial thyme oil products averaged 43 percent control over three years, 2019 to 2021, with three to six applications. Essential oils, such as thyme, mint, cinnamon and oregano, have antimicrobial properties and, in laboratory settings, have reduced the virulence of Erwinia amylovora, the bacterium that causes fire blight.

DuPont envisions the biopesticides being used as rotational products in organic programs, following biologicals such as Blossom Protect and soluble coppers.

Johnson presented final results of his antibiotic alternatives trials at the apple crop protection review.

He had the most success with Actigard (acibenzolar-S-methyl), a compound that elicits the plant’s own defense mechanisms. In 2020, Actigard applied during bloom time significantly reduced infections. Prebloom timing was a different story. Neither Actigard, Apogee (prohexadione calcium) nor Regalia (Reynoutria sachalinensis) significantly suppressed fire blight when applied prebloom.

He recommends more research into Actigard.

“I still don’t think we know everything we need to about how to use it,” he said.

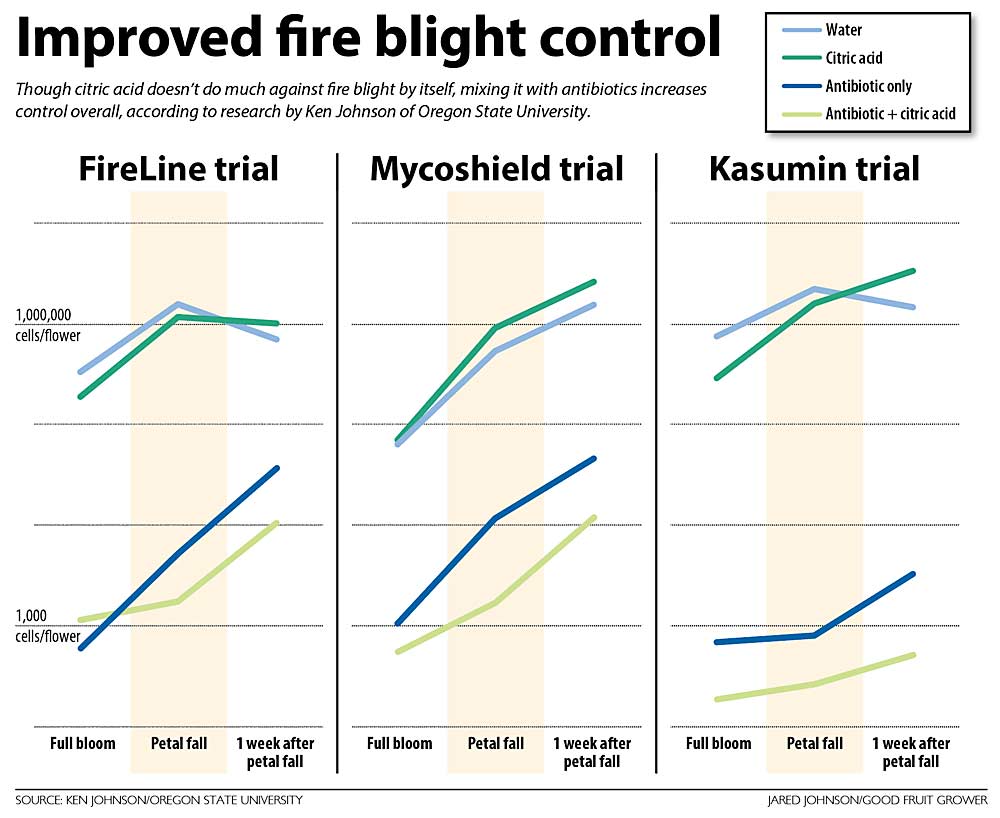

In February, at his first in-person presentation in two years, Johnson told growers at the Winter Horticulture Meeting in Hood River, Oregon, about efforts to get more bang for their antibiotic buck by lowering the pH of treatments.

“The topic is: Does dropping the pH of antibiotics in the spray tank improve control?” he said.

The answer, he’s convinced, is yes. For five years, Johnson has been experimentally adding citric acid to spray tanks and ending up with lower populations of fire blight bacteria than with antibiotics alone. The citric acid did not cut down on fire blight incidence by itself. There’s something about the combination of the acid and the antibiotics. FireLine (oxytetracycline hydrochloride), Mycoshield (oxytetracycline calcium complex) and Kasumin (kasugamycin) all showed the same effect.

“We’re doing something to the antibiotic, that’s what we think,” Johnson said.

He also found citric acid caused antibiotic residues to remain at an effective concentration longer than after spraying antibiotic by itself, making control last longer.

And it doesn’t increase russeting either, he found. Growers sometimes get nervous about acidifying spray tanks, he said, but unbuffered citric acid at a pH of 3 lowered the pH of the floral surfaces from a normal of 5.9 to between 5.3 and 5.7 pH, Johnson said, apparently not enough to cause russeting.

“We can’t find a marking effect in an … unbuffered citric acid situation mixed with the antibiotics,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment