Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower;

Photo: TJ MUllinax/ Good Fruit Grower)

Editor’s note: The story has been corrected to reflect one of the two causes of high trucking prices is increased demand for trucking services during the pandemic.

Chalk up one more trend exacerbated by the coronavirus.

Shipping prices had already been rising the past several years due to a continued and growing shortage of truckers in America. The pandemic only made things worse.

“If you look at it now, truck rates are going through the roof,” said Eric Jessup, a Washington State University economist. And truck rates influence everyone’s bottom line, even growers’.

Jessup, an expert on agricultural transportation and logistics, discussed freight costs and shipping challenges in early December at the Batjer Address, one of the highlights of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Annual Meeting.

The pandemic and its restrictions on dining, travel and in-person shopping has increased the demand for trucking services, particularly from home delivery firms such as FedEx and Amazon. That means fewer trucks and truckers to haul shipments of apples and pears, which offer lower margins. Meanwhile, the trucking industry relies on an aging workforce, many of them too vulnerable to work through the pandemic, even though trucking was labeled as an essential industry.

“Take the two of those; it’s leading to extremely high truck rates right now,” said Jessup, director of the Freight Policy Transportation Institute, funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

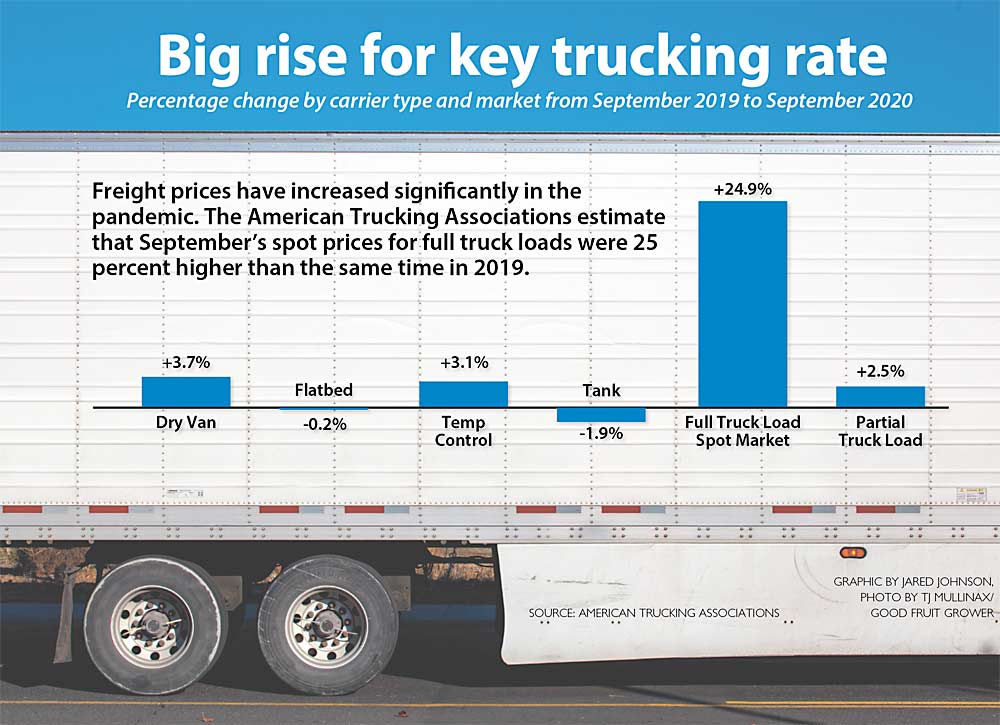

In September, the American Trucking Associations estimated spot prices for full loads were 25 percent higher than the same time in 2019, with smaller increases for dry van, temperature control and less-than-full truck loads. Most tree fruit ships under f.o.b. prices, with buyers arranging the transportation, not the spot market, but the prices are an indicator of an overall rise in freight costs.

The trucking industry, like everyone else, was caught by surprise by the pandemic and did not have time to pivot in the spring, said Jon Samson, executive director of the Agricultural and Food Transporters Conference, a part of the American Trucking Associations. For example, there was plenty of demand for groceries, but companies that specialize in hauling cars, for example, can’t switch to fruits and vegetables overnight because of geography and the physical design of the haulers.

Companies have been adding capacity since then and things should be better in 2021, he said. In the longer term, academic and industry experts have been trying to redesign the food supply chain to “make it more agile,” he said.

A toll on the industry

Trucking rates took a toll on the industry last year. Retailers will either push up the price of the fruit to compensate, which could decrease consumer demand, or choose to stock other products, marketers said.

The rates affect grower returns, too, said Roger Pepperl, marketing director for Stemilt Growers of Wenatchee. About 60 percent of fruit is shipped based on competitive ad promotion prices, which retailers can’t change overnight. So, they try to make up for the higher shipping cost with lower prices paid to packers, which translates to smaller grower returns.

“Ad pricing and regular pricing both can move up over time, but it takes months,” Pepperl said.

Normally at this time of year, shipping a load of apples from Washington to the East Coast runs about $9,400 per load, said Josue Gutierrez, transportation manager for Sage Fruit Co. of Yakima. This year it’s about $11,000. Intermodal rates are high, too, he said.

Due to the lack of economic activity caused by the coronavirus, trucks come less often from the East, making them more scarce in the Pacific Northwest, which produces most of the apples. Some trucking companies shut down entirely, Gutierrez said. Retailers and brokers have been more willing than usual this year to make multiple stops to fill up partial loads, he said.

The high trucking prices also pit apple growing regions against each other, said Steve Smith, marketing and business development director at Washington Fruit and Produce Co. of Yakima. Freight costs naturally go up with distance. He has noticed truck prices from Yakima to the East Coast running between $8 and $12 per box, unusually high, he said. That gives Michigan and New York growers a geographical advantage in Eastern population centers. The Washington label on apples commands a price premium, but that will carry retailers only so far, he said.

Rising freight costs also intensify the competition for shelf space with other fruits and vegetables. If retailers try to raise prices of apples from $1.69 per pound to $1.99, oranges at 99 cents per pound start to look more attractive.

All these freight dynamics wash out onto the initial producer. “It’s a very important component to the grower,” Smith said.

Jessup predicted all the changes will have long-term effects. For one, the trucking industry will only speed up its move toward autonomous vehicles, electric-powered trucks and hydrogen fuel cell-powered trucks, he said.

Meanwhile, Jessup is concerned about the coronavirus’ toll on the nation’s transportation infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers already gives the country’s highways and bridges poor grades, and the coronavirus has taken a big bite from state transportation budgets, which rely heavily on gas taxes.

There might be some shift to source food locally but no overall shortening of the supply chain, he said, as some economists have predicted. The masses will still shop at Costco and Walmart, and those retailers will purchase from reliable producers wherever they are in the country. The population will simply be too large for anything else. By 2045, America’s population will grow by 70 million, according to a 2017 report by the U.S. Department of Transportation. That’s about the current size of New York, Florida and Texas combined.

“Do you think you’re going to source all that food … from a locally grown CSA?” Jessup said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment