Farmworkers from the Caribbean have been coming to work every season at Schuyler Farms in Norfolk County, Ontario, for as long as both Brett Schuyler and his dad can remember.

“On our farm, it’s a career for them,” Schuyler said. “They are extremely skilled, capable people. We’ve been spoiled a bit with this skilled workforce that comes back every year.”

But this year, he had to start the season without his career workers from Trinidad and Tobago, and in early April he was still unsure if they would be able to come at all.

The longstanding reliance on the Caribbean and Mexican farmworkers who provide the critical workforce for Canadian specialty crop producers appeared to be in jeopardy in the spring of 2020, as the rapid spread of the new coronavirus led to travel restrictions and delays.

The situation thrust growers and industry groups into action, calling on political leaders to find solutions that would remain protective of worker and community health while also giving farms the labor they need to grow and harvest food. It also put a very public spotlight on the often-under-the-radar program growers have relied on since the 1960s.

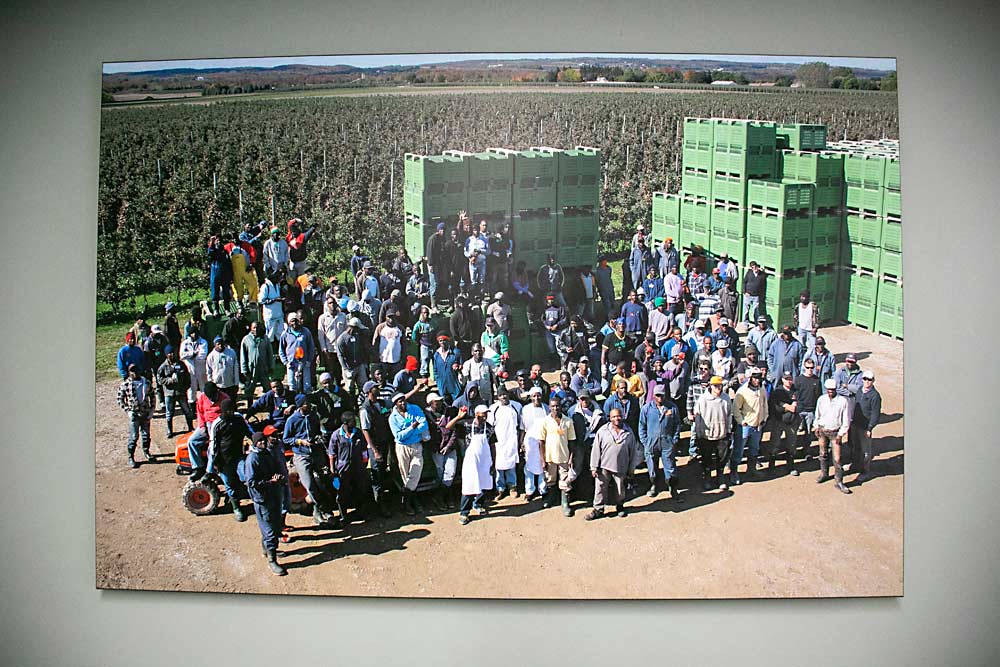

Advocacy for the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, SAWP, isn’t new to many Canadian growers. In 2018, the Canadian Horticultural Council launched the Heartbeat project, a documentary film celebrating the international farmworkers who make possible the country’s specialty crop production.

“It’s not very well understood by people outside of ag why these workers are so critical and why they need to be brought in,” said Karl Oczkowski, communications director for the council. “We produced the documentary with the aim of clarifying the misconceptions that are out there and giving the growers’ and skilled workers’ side of the story.” (Click the link to view the video, “Heartbeat – A Celebration of International Farm Workers,” from the Canadian Horticultural Council.)

That side includes the economic benefits of the program to rural Canadian communities and how the paychecks workers send home support their communities — one grower called it Canada’s largest and most effective foreign aid program.

Such vocal advocacy for a program that still entails plenty of paperwork, bureaucratic regulations, expenses and liabilities might surprise U.S. growers whose main conversation about the H-2A guest worker program focuses on needed reforms, even as they apply to bring in more and more workers through it every year. But Canadian growers say public ignorance of the importance of the program — made more visible by the debate over allowing foreign workers into the country in the midst of a pandemic — poses a threat to their businesses and the country’s food security.

Coronavirus threatens critical workforce

About 50,000 seasonal farmworkers come to Canada every year, staying up to eight months. To hire them, growers have to prove that they have first tried, unsuccessfully, to find Canadians to fill the positions. Under the SAWP program, growers pay Canadian wages, plus travel costs, housing and health care.

“The entire ag industry in this country has been built on the availability of foreign labor. Not cheap labor, but foreign labor,” said Chris Hedges, an apple grower from Norfolk County, Ontario. “This has really opened our eyes that this thing doesn’t work if we don’t have the people.”

This, of course, refers to the spring of 2020, when Canadian leaders issued travel bans to reduce the spread of coronavirus. Weeks of limbo followed as growers pushed to find ways to get thousands of scheduled farmworkers into the country — 4,600 just for Ontario in April — and figure out how to isolate them for 14 days before bringing them into a work and housing environment set up with social distancing measures. (See “Housing during the pandemic,” Page 8).

“That was a very stressful time for farmers in Ontario, not knowing whether they would have the human resources they need to plant spring crops,” said Bill George, a grape grower and chair of the Ontario Fruit and Vegetable Growers’ Association. But after weeks of delays, the first chartered flights from Jamaica arrived in early April, and workers headed into 14 days of isolation before they could start working — the same policy required of Canadians returning from abroad, he said.

The challenge of the isolation policy is creating isolation in bunkhouses. In Norfolk County, local officials set a rule of three farmworkers per housing unit, regardless of house size, Schuylar said. That meant he could only bring in 33 workers from Jamaica in his first wave, despite housing capacity for 220. After 14 days, he can consolidate those workers and bring in another wave.

In Nova Scotia, however, growers were expecting to wait until early May to get farmworkers that had first been expected in late March, said grower Lisa Jenereaux. The province planned to collectively put farmworkers up for the isolation period, perhaps in hotels or other facilities where it would be easier to ensure isolation than in farmworker housing. While difficult for farmers, she said it’s the right call to protect everyone’s health and assure the community that incoming workers pose no health threat.

She delayed planting trees and her family of five was basically running the diversified farm themselves, she said, planting potatoes and carrots and tending to the spring needs of 100 acres of apples. Usually about a dozen workers arrive in the spring, followed by another wave in the summer. She can’t train locals to fill in the gaps, except simple jobs such as cutting out root suckers, because she can’t risk her own health to train people who have no experience doing orchard work.

Seasonal farmworkers bring years of experience and skills to the job — as every interviewed grower emphasized — filling positions that can’t be easily replaced by Canadians laid off from other sectors due to pandemic closures.

“This trial that we are going through now, it does highlight even more that this is a special program we need to protect,” Jenereaux said. “If these workers do not come, farming as we know it today will be different. If one year they cancel the program, I am done with strawberries and I am done with apples. There’s just no way to look after those crops without these workers here.”

Long-standing relationships

While U.S. growers turned to the H-2A program in droves in recent years to replace a dwindling local, and often undocumented, workforce, many Canadian growers have been relying on the international farmworker program since it began with 264 Jamaican workers harvesting apples in Ontario in 1966. Paying for workers’ flights and housing and health care have just been part of the cost of doing business for decades, Schuyler said.

His family farm typically brings in about 150 seasonal farmworkers from Trinidad and Tobago, and most have been with the family over 10 years. Six or seven years ago, at the urging of Trinidad and Tobago’s government, Schuyler Farms hired the first crew of women from that country, and it’s been a huge success. “These ladies take tremendous pride in out-picking the men,” he said. Several of the women on his crew shared their stories with the Heartbeat project, citing confidence gained by learning new skills and pride in supporting families back home.

Schuyler Farms expected to bring in 70 more Jamaicans this year, after acquiring another farm. “We want to bring up that people who’ve been coming to that farm for 15 years, that’s a huge asset,” he said.

The long-standing relationships many growers have with their seasonal workers play into why many are passionate advocates for the program. Most fruit and vegetable farms are smaller, family-run businesses that every year may bring up 10 to 25 workers whom they get to know well, George said. “There’s very, very little turnover,” he said. “These workers become parts of the family; my kids grew up with them.”

Most workers still want to come to Canada, despite the pandemic and the isolation requirements, George said, because they need the work and they trust their employers to take steps to protect their health. In mid-April, the government announced it would pay growers $1,500 for each worker to cover the cost of their wages during isolation and other costs associated with putting the health precautions in place.

Public perception

In Norfolk County, where Schuyler and Hedges farm, the rural community sees an influx of about 7,000 Caribbean and Mexican farmworkers every summer. Sometimes, that causes some tension, because locals still view the workers as outsiders, even though many of them have come for years, shopping in local stores and eating at local restaurants on Friday nights.

Schuyler said he hates to think that his workers may feel unwelcome in the community, especially as the coronavirus stokes fears of outsiders. He and Hedges both said they want to find ways to integrate farmworkers and embrace the cultural diversity — and delicious cuisine — they bring to the area.

“We’ve messed up a bit that they are not more a part of the community,” Schuyler said. “What I know is that if we had a community that was proud of the agriculture sector and the people who make it happen, it would be easier today to navigate this COVID-19 situation.”

The persistent perception that farmers are displacing Canadian workers with lower cost labor simply isn’t true, growers said. Workers start at $14 Canadian an hour.

As for hiring locals, “we’re making huge efforts to get local kids on the farm” at harvest, Schuyler said, along with backpackers. Those efforts help keep the community connected to agriculture, he said, but only occasionally result in the farm finding long-term employees.

“If we could get enough people to come and work on the farm and go home every night, that would be great,” Hedges said. Local workers would be lower cost and lower liability. With seasonal international workers, “if someone cuts their finger cooking dinner, it’s on my workplace safety.”

Hedges felt fortunate he already had a dozen Jamaican workers arrive on his farm before the coronavirus restrictions were put in place. “Without them I’d be dead in the water,” he said. But the logistics of ensuring social distancing in housing and transport has been a challenge — one he expects will get harder when or if his second wave of workers arrives in June.

It’s an unprecedented challenge, but growers are used to weathering unpredictable difficulties.

“There’s always something that can knock you flat, so over time you become more resilient to things,” Hedges said. “We’re hoping by September that this thing is over. If it’s not, we have all got big problems beyond tree harvest.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment