Drones now drop sterile codling moths over thousands of acres of apples in Washington, but two leading tree fruit entomologists continue research efforts aimed at fine-tuning the use of sterile insects by optimizing delivery methods and timings.

Larry Gut of Michigan State University and Betsy Beers of Washington State University discussed their findings on delivery methods and rates at industry meetings and with Good Fruit Grower this winter.

Gut’s trials look at whether insects should be distributed uniformly throughout the orchard or from a single release point near the center. He’s also weighing drone versus hand delivery.

Drones are efficient and quick, but moths appear more likely to stay within the boundaries of the orchard when distributed by hand. Gut found moth recapture is more efficient when the drone hovers closer to the tree canopy, about 15 meters above the ground. The higher the drone goes, the lower the rate of recapture, he said.

The sterile moths come from a Canadian facility that irradiates them with cobalt. The sterile males compete with wild males, and the program’s aim is to eliminate fertile matings and, thus, offspring. So far, Gut’s project has found that sterile males mating with wild females can reduce egg hatch by more than 90 percent. The method costs more than $400 per acre, however, and needs to be more economical if it’s going to be a practical strategy for growers, he said.

Sterile release achieves good control during the first generation of codling moth, but it doesn’t seem to be as effective during the following generations. Gut said future research will seek to find out how many sterile moths, exactly, are needed to suppress codling moth and whether or not the method could eventually eliminate insecticide sprays.

Rob Curtiss, an MSU graduate student working with Gut, is studying sterile insect release near Wenatchee, Washington. He’s been working with Gut since 2018. They decided Curtiss would do his research in Washington because of easier access to sterile moths.

There’s still a lot of research to do, but Curtiss thinks sterile insect release has potential in Michigan as well as Washington, despite the different environments, disease pressures and costs. Here are some of his takeaways so far:

—Sterile moths are mobile and can quickly distance themselves throughout an orchard when using both hand and drone release methods.

—Single-point releases from the center of a 10-acre block are effective at ensuring moths get to the edges of the block.

—He found moths released via drone have a higher recovery rate than those released by hand.

—He also found a higher recovery rate of sterile moths from trellised, high-density orchards than from older, low-density plantings.

—Sterile moths released in low numbers still have a measurable impact on wild populations.

—In orchards with pheromone mating disruption in place, moths only move about half as far as in other orchards.

Beers, a WSU entomologist, shared findings from her research trials that illustrate both the potential and the remaining questions about how best to use sterile insect release.

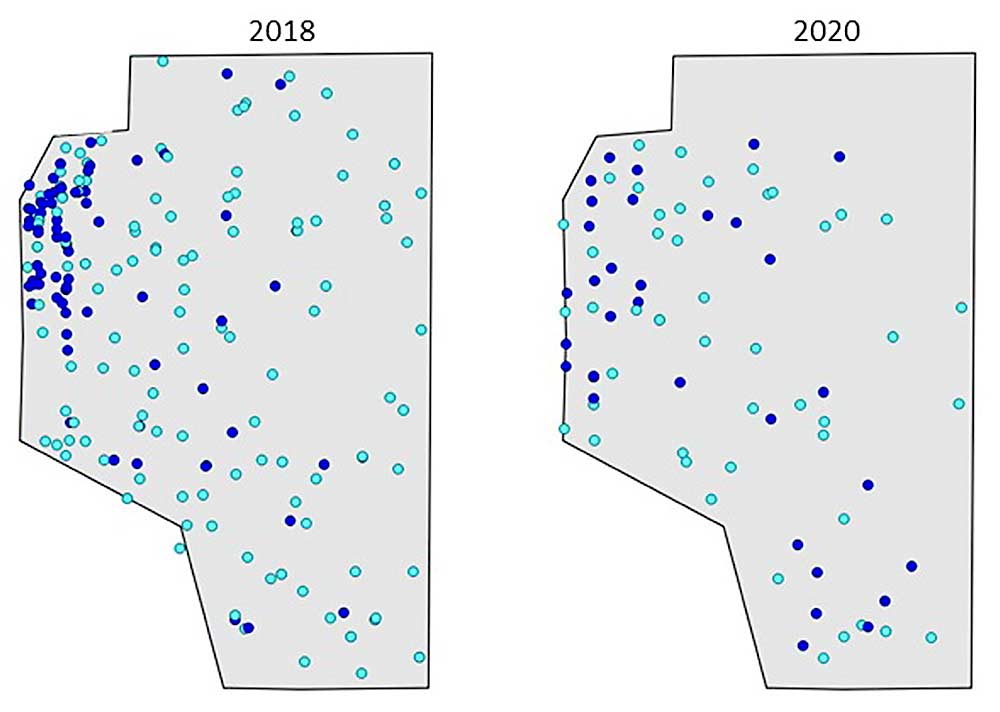

She successfully eliminated hot spots after three years of treatments in commercial blocks, and fruit damage steadily declined in most of the test blocks over the three years. However, sterile moth release treatments made almost no difference compared to control blocks in 2019 and 2020, regardless of release rate, even though it cut damage roughly in half in 2018. She’s unsure why, though biological variability is common and she did not monitor the consistency of other tactics the orchardists might have used.

“The success of SIR will depend on the grower’s ability to put all the components together,” she said.

Understanding the best practices for SIR will take time, she said. Three years of research in Washington does not hold a candle to the decades of work done before British Columbia even started their release program, she said. Also, it took many years to fine-tune the codling moth mating disruption methods the industry now relies on so heavily.

Beers and Gut received funding from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission for the past three years. Beers also had funding from the Western Integrated Pest Management Center.

Beers shared a few interesting side notes, such as the fact that aerial sterile insect release worked over netting. The moths found their way under a three-sided net with a few uncovered seams.

Beers also found a noticeable improvement with releasing moths by hand directly into canopies compared to by hand on the ground. The canopy method mimics the natural behavior of the moths. Beers’ ground releases are closer to the way Canada releases sterile codling moths, though not exactly the same. The Canadians scatter sterile insects along the ground with blowers mounted to ATVs. Beers and her team did not have those tools.

The commercialization of drone release and the research comes at a pivotal time in codling moth management history. The pest has anecdotally been on the rise in the Northwest, and the industry has formed a codling moth task force that is conducting grower surveys. (See our Good to Know column: “New task force tackles codling moth.“) •

—by Matt Milkovich and Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment