Ever since spotted lanternfly first appeared in Pennsylvania vineyards in 2014, there have been plenty of reports about the ways the phloem-feeding planthopper damages grapevines.

Those reports have mainly been anecdotal, however. Growers and researchers knew that some grapevines declined — or even died — in the months following SLF infestations, but until recently, they didn’t have solid data to prove the connection.

After a few years of research, data is starting to appear. In October, Penn State University researchers published the results of a study investigating grapevine-SLF interactions. They concluded that grapevines could withstand low SLF population densities, but feeding from higher population densities could cause a vine to shut down well before it’s supposed to, said researcher Heather Leach.

Leach was a Penn State Extension associate at the time the study was conducted in 2019 and 2020. She said the published paper marks the first scientific documentation of SLF-grapevine damage in the United States, and the first step toward developing data-backed population thresholds growers can use to help them decide when to spray.

The research team conducted the study in a Southeast Pennsylvania commercial vineyard, focusing on the effects on two grape varieties: Riesling and Marquette. During harvest, they enclosed the grapevines in cages and introduced adult spotted lanternflies into each cage. Some vines were exposed to lower population levels of SLF, some to medium levels and some to higher levels. They found that higher populations of SLF affected carbohydrate and nitrogen dynamics in the plant, both elements important for crop production and health. Leach did a separate study that showed reduced clusters per shoot with increasing SLF infestations, she said.

In the main study, the spotted lanternfly adults were allowed to feed on the vines unmolested for about a month, which would never happen in a commercial vineyard, said postdoctoral scholar Drew Harner.

“We tried to test the limits of what a vine could withstand with heavy populations and a prolonged period of time,” Harner said.

According to their findings, intensive late-season phloem feeding by large SLF populations (eight or more per shoot) can induce carbon limitation, with the potential for negative effects the following year.

Penn State associate professor of viticulture Michela Centinari said many factors play a role in long-term vine health, but the study confirmed that SLF can contribute to long-term vine decline if not properly managed.

In partnership with Penn State entomologists and plant pathologists, the researchers will continue to study SLF’s effects on grapevines and have expanded their trials to measure effects on Cabernet Franc and Chardonnay. They want to learn if the pest transmits pathogens while feeding on vines. They also want to study SLF’s nymph stage and how nymph feeding affects vines, Harner said.

Leach hopes the new findings will help calm grower anxieties about the invasive pest. Alarming coverage of SLF’s fruit-killing reputation has caused growers to spray much more chemical than needed, even if there’s only a handful of bugs in the vineyard. She hopes greater knowledge of spotted lanternfly will turn it into one more problematic — but manageable — vineyard pest, she said.

“We have the tools to manage it, and they’re constantly improving,” Leach said. “This is not the nail in the coffin for U.S. grapes.”

Outward expansion

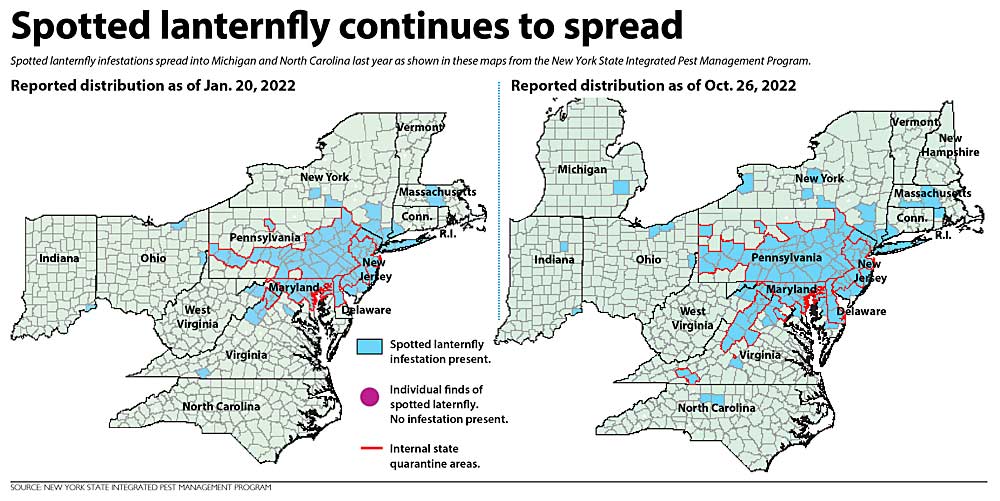

As researchers learn more about spotted lanternfly, the invasive pest continues to spread outward from its mid-Atlantic epicenter.

After lower activity in 2021, SLF reinfested several Southeast Pennsylvania vineyards in 2022, though infestation rates, as always, weren’t uniform. SLF expanded into South-central Pennsylvania, too. Fortunately, growers know how to manage it better by now, so they hope there will be less damage overall, Centinari said.

SLF pressure was “quite intense” in Northeast Maryland vineyards in 2022, a continual increase over the past few years. And by fall, significant populations were showing up in the research vineyard at the Western Maryland Research and Education Center in Keedysville, said Joe Fiola, viticulture and small fruit specialist with University of Maryland Extension.

In August, a small SLF population was discovered in Southeast Michigan. Leach, who recently joined Michigan State University’s Department of Entomology as a Northwest Michigan-based research technician, said it might be a few years before the invasive pest reaches the state’s grape-growing regions in significant numbers, but it will happen eventually. SLF is more likely to pose a problem in Southwest Michigan vineyards, where the climate is more suitable and there’s more tree of heaven, one of the pest’s preferred host plants. It probably won’t be as much of a problem in Northwest Michigan, she said.

The best thing Michigan growers can do right now is thoroughly scout their vineyards, Leach said.

“The biggest thing is awareness,” she said. “Spotted lanternfly can’t be stopped, but it can be delayed.”

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment