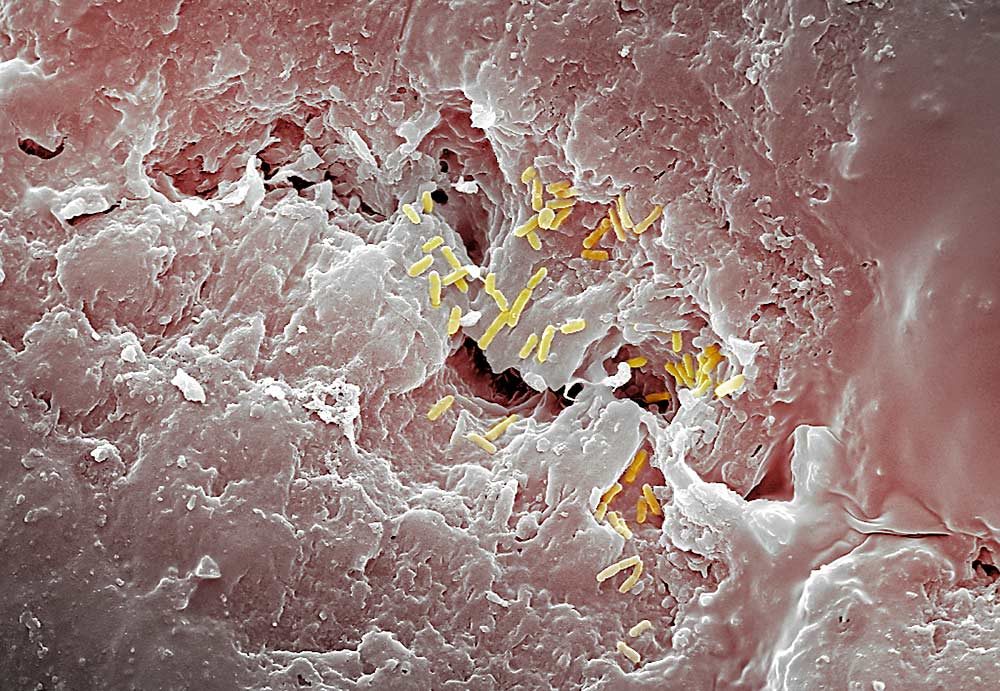

Apple skin may seem smooth, but fissures skinnier than human hair can harbor bacteria. Listeria, for one, may lurk in these so-called microcracks.

Washington State University researchers have an answer, though. They have determined that augmenting cleaning solutions with surfactants drastically improves the removal of pathogens by allowing the sanitizers to penetrate those cracks.

“We want to add something to our cleaning solutions that will help us spread on the apple and cover the apple evenly and help us to detach bacteria, to get into all those microcracks,” said Ewa Pietrysiak, a WSU food science researcher.

Pietrysiak, who grew up on a fruit orchard in Poland, spent months in a laboratory inoculating the surfaces of apples with a benign strain of listeria. Then, she alternated cleaning them with water, peracetic acid and peracetic acid mixed with three different surfactants. Peracetic acid is a common packing line sanitizing formula.

Her results showed the surfactant mixtures were significantly more effective at cleaning than sanitizers alone. That’s the conclusion they are sharing with the industry now, although she and her colleagues declined to share data with Good Fruit Grower until they publish their work in a scientific journal.

Surfactants in cleansers is an old idea. That’s what puts the foam in soap, breaking through water surface tension to wash away dirt from hands, dishes and clothing.

They work on other fruits and vegetables, too, said Faith Critzer, WSU’s produce safety extension specialist. Before joining WSU, she participated in similar surfactant projects involving packing tomatoes and peppers at the University of Tennessee.

In apples, the surfactants penetrate the fruit’s natural wax coating that nature designed to keep moisture in and pathogens out. The wax works, for the most part.

“We know that wax coating isn’t 100 percent perfect,” Critzer said.

Surfactants in the packing line could help make up the difference by ushering the sanitizers into those tiny cracks, most likely as additives in dump tanks or flumes, Critzer said, rather than the spray bar where the foam would cause problems.

In May in a lab at WSU’s Pullman campus, Pietrysiak — then a doctoral candidate — spritzed peracetic acid on a Gala apple. The liquid beaded up like rain on a freshly waxed car, meaning it didn’t penetrate. Onto a second apple, she sprayed peracetic acid with surfactants. The fluid spread out into a thin film, showing it worked.

“Here you can see it covers better,” she said.

Working under the direction of Girish Ganjyal, a WSU professor of food science, Pietrysiak and her colleague, graduate student Julianne Kummer, ran the experiments by inoculating the surfaces of apples with Listeria innocua, a nonpathogenic cousin to Listeria monocytogenes, the foodborne pathogen. After the three treatments, they peeled the apples, emulsified them, added the juice to petri dishes with a listeria-friendly medium and counted the colonies that developed.

They tested three types of surfactants — sodium dodecyl sulfate, lauric arginate and polysorbate 20 (Tween 20). They found no statistical difference between them, but all outperformed sanitizers alone. They experimented on Gala and Granny Smith, seeing little difference between varieties.

Their work was funded for 2019 by a $47,000 grant from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Pietrysiak has since earned her doctorate, though she and Kummer plan to apply for more funding to continue their research through 2020 with different surfactants, sanitizers and apple varieties. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment