A relatively new Oregon State University horticulturist suggests the industry takes a renewed look at a pear rootstock with some history in the Columbia River Gorge. Industry members are cheering her on.

Kelsey Galimba discussed the potential for amelanchier rootstocks at OSU’s annual Winter Horticulture Meeting in late February in Hood River.

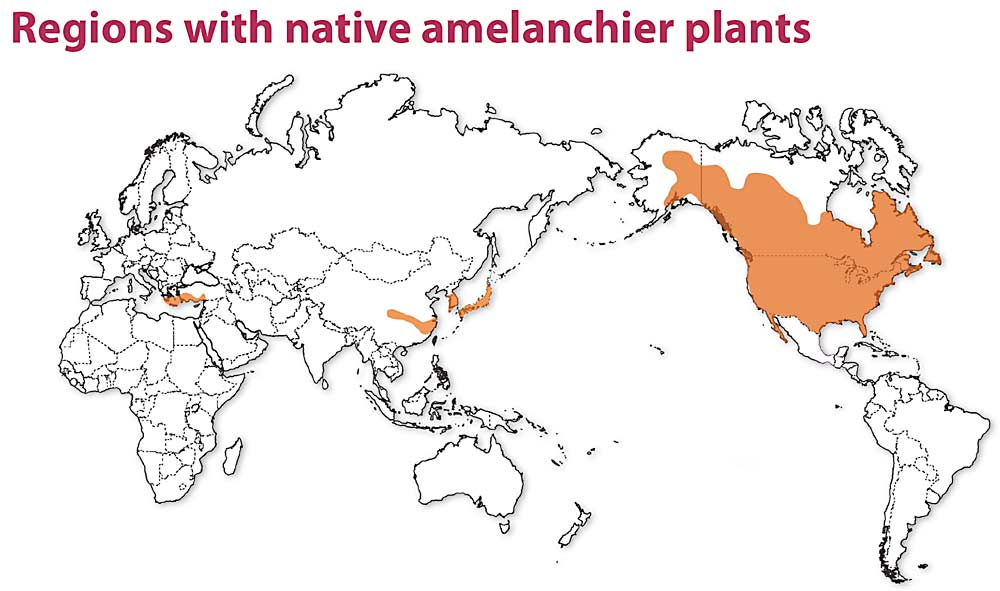

Amelanchier is a genus of flowering shrubs in the rose family, native to North America, which have been developed into rootstocks compatible with Comice and Beurre Hardy pears in Germany.

“I think this is definitely a species that is worth following up on,” Galimba said.

She hopes to establish a rootstock trial orchard with several amelanchier selections within a couple of years at the university’s Mid-Columbia Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Hood River.

Pear producers have been searching for ways to modernize orchards to high-density, trellised systems, much like apple growers, but the industry lacks a dwarfing rootstock that can handle the cold winters of the Pacific Northwest, where most of the nation’s pears are grown.

Northwest researchers, nurseries and producers have been experimenting with amelanchier and quince for more than 10 years. The Hood River research station once had its own trial blocks of both, planted by Todd Einhorn, who held Galimba’s position before moving to Michigan State University. But they have since been removed.

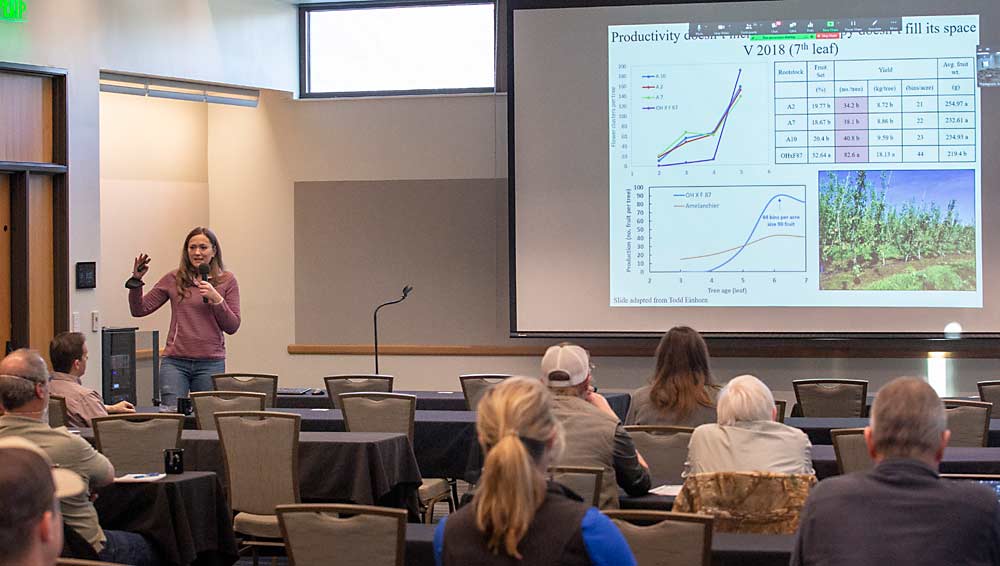

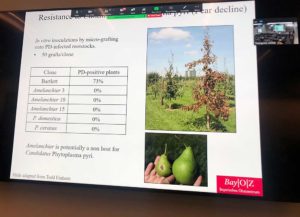

Amelanchier rootstocks check many of the right boxes, said Galimba, who based much of her February presentation on Einhorn’s research. They are cold-hardy up to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, produce high yields of large fruit in early years, stay compact and resist the phytoplasma that causes a disease known as pear decline. And they grow to about 40 percent of full size. The industry standard, Old Home by Farmingdale 87, is 70 percent of full size.

Galimba started at OSU’s Mid-Columbia Agricultural Research and Extension Center in late 2020. After some urging from the host of one trial block planted in 2016, Galimba harvested fruit in 2021 and collected data. Generally speaking, cultivars on amelanchier roots with Comice interstems are filling canopy space with appropriate vigor and produced good yields with big fruit, she said.

But there are some drawbacks.

The amelanchier selections OSU has trialed are incompatible with Bartlett and Anjou, a problem that will require interstem grafting. That could add a year’s wait and cost in the nursery before growers can plant. They will require detailed management, such as click pruning, heading cuts and blossom thinning for young trees, to make sure they grow enough to fill the canopy. Also, the rootstock still needs more long-term trials to answer questions about how to manage nutrition, irrigation and training, she said.

That’s true, said Dave Weil, owner and founder of Tree Connection, the Dundee, Oregon, tree brokerage company and rootstock producer that brought amelanchier selections to the Northwest from a German breeder in 1999 and owns the master license to it. It’s not ready for commercialization yet, he said.

“Until we can do that, I don’t see how you can take the risk of planting this,” Weil said.

Weil also wants to study compatibility problems through cellular analysis of graft unions. Sometimes, latent incompatibility can lurk undetected in trees for several years before they start showing weakness, he said.

A lot of the answers may lie in Adam McCarthy’s 2-acre block of green Anjous on Amelanchier 15 rootstocks with Comice interstems. Planted in 2019, the young trees at 2.5 feet spacing have filled their space so quickly, the Parkdale, Oregon, grower may crop in the third leaf this year, just to calm the vigor — a short timeline in the pear world.

He has some inconsistencies in his block, but some of the trees were smaller than he would normally plant because Tree Connection had only so many to offer him. Also, many of those inconsistencies could be answered by a few more years of management trial and error.

“What happens in the next two to three years is going to be very interesting,” said McCarthy, chair of the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association and a former board member of Columbia Gorge Fruit Growers.

McCarthy has the Amelanchier 15 trees on drip irrigation, also unusual in pears.

As for management questions, those still exist for traditional roots, too, he said. For example, he discovered by accident that young Anjous respond to water stress by reducing vigor and pushing fruit earlier.

“Even if we get a new rootstock, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to solve all our problems,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment