Ask almost any grower what tops their technological wish list, and the answer will be harvest automation. Yet almost all specialty crops are still harvested by hand, despite the proliferation in ag tech startups over the past decade and the challenges of labor availability and rising costs.

Dennis Donohue, director of Western Growers Center for Innovation and Technology, calls the need for harvest automation a race against time and a race in which time is running out. That’s why in February, Western Growers and collaborators, including the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission and other commodity groups, launched a new initiative to accelerate harvest automation.

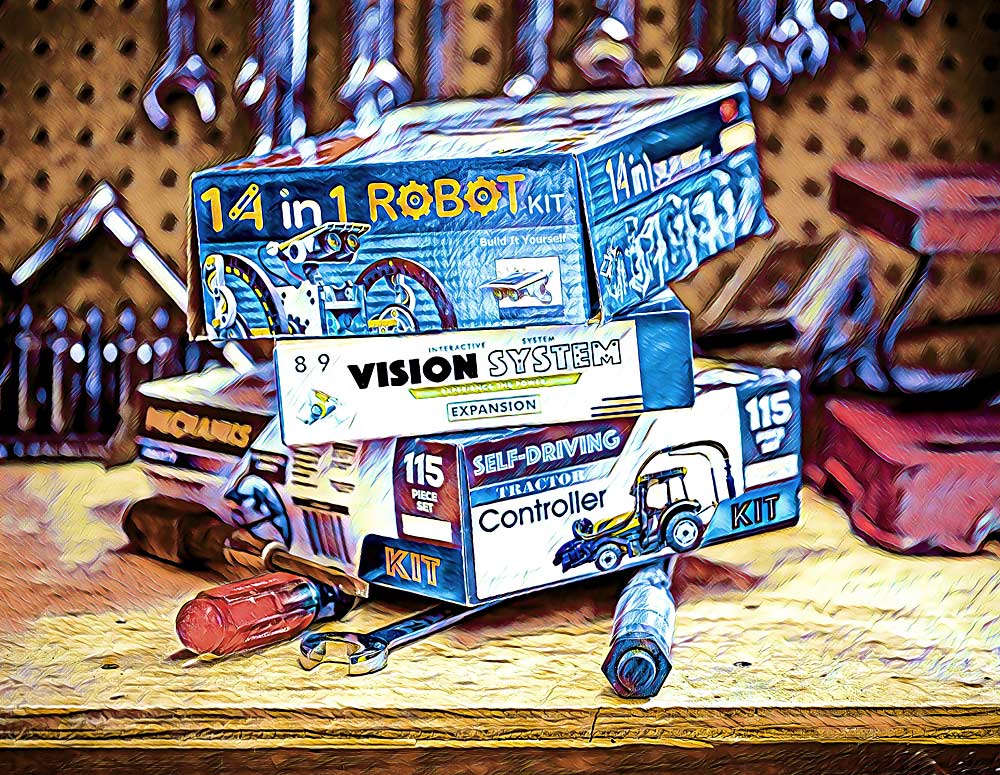

The Global Harvest Automation Initiative aims to foster the development of automation building blocks that can then be customized by commodity needs — think plug-and-play robotic arms and vision systems — to reduce the need for each specialty crop to start from scratch.

The idea stemmed from conversations with ag tech companies and Western Growers members about the challenges they face in harvest technology.

“If we are overly fragmented and can’t solve the problem individually, how do we leverage together?” Donohue said. Specialty crops are so, well, specialized that it can be hard for tech companies to see the potential payoff in developing specialized technology. “This is not an ag tech issue; this is a business case issue. We need to take a more multidisciplinary, crop-collaborative approach to solve the problem,” he said.

All harvest robots, whether picking strawberries from the ground or apples from a tree, need the same core technology in terms of a self-driving platform or tractor to move through the field, vision systems to detect the fruit to harvest, artificial intelligence for processing all the imagery into functional information, and a robotic arm that moves toward the ground or tree or vine, said Walt Duflock, Western Growers’ vice president of innovation.

“Every startup we know that is building harvest tech is building all of that from the start,” he said. Why should startups waste time designing a platform or tractor to move their machines when “we already have a bunch of great tractors from John Deere and others? Let’s come up with ways for these people to build devices that operate on the back of an existing tractor.”

By supporting the development of these building blocks — a standard tractor, vision systems, processing power and robotic arms with reliable, field-proven technology — companies can focus on the end-effectors, the devices on the end of a robotic arm that will need to vary by crop and other crop-specific challenges, Duflock said. That should both pick up the pace of commercialization and lower the cost of harvest technology.

Even for the apple industry, the specialty crop leader in automated harvest, participating in the initiative makes sense, said Ines Hanrahan, director of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

“We want a cost-effective machine that’s affordable for everybody. We don’t have a machine that can replace our labor. They are not fast enough or cheap enough yet,” she said. “‘We feel this is the final piece of the puzzle we’ve been missing.”

The experience of the apple industry’s investment in harvest automation shows how much time and money it takes to develop and then commercialize such complex equipment from scratch, she said. Developing a supply chain of sorts, common platforms that can be customized, will make future harvest tech more affordable.

Jeff Cleveringa, a research commission board member, agreed. The two robotic apple harvest companies the commission has funded over the years, Abundant Robotics and FFRobotics, are doing good work and continually making progress, he said, “yet tomorrow I can’t go buy one.”

Collaborating with a variety of companies with expertise in different components of complex harvest systems just makes sense, said Cleveringa, who heads research and development for Starr Ranch Growers. For example, FFRobotics licensed bin-filling technology from MAF Industries and uses a platform designed by Automated Ag, thanks to some help from the commission playing technology matchmaker, he said.

“We said, ‘Don’t reinvent that, just license it,’” he said. “This partnership with Western Growers will introduce us to partners who build components that are field-ready for other applications.”

Having the tree fruit industry join the effort validates the approach, Donohue said.

“It was an important message to send to our stakeholders: ‘Look, the apple industry has been at this a long time, full industry cooperation, and funding is not the issue, but progress is slow and it’s a race against time,’” he said.

The new initiative will take advantage of the relationships Western Growers has built with ag tech companies in recent years through its Center for Innovation and Technology. Based in Salinas, California, the center facilitates technology development by identifying grower needs, identifying promising technologies, helping startups set up farm trials and communicating progress.

“We have a playbook we can use on any ag problem we want to solve,” Duflock said. “We’ve worked with a broad range of startups across ag tech. Now, let’s really focus on one key area.”

One piece of that playbook: a crop-specific roadmap for automation and mechanization that shows which companies are providing automated solutions to real farm customers and which are doing trials or R&D, he said.

“It’s a market map, if you will, to tell growers: ‘Here’s who you want to watch for,’” he said. “The startups, when they see it, they will say: ‘We need to be on that.’”

The initiative will also focus on assessing the impact of automation technologies. For technology to succeed, it has to be cost-effective, Duflock said, and they aim to keep viable economics at the fore of every promising technology.

With a significant investment (Western Growers declined to share cost estimates before this issue went to press), Donohue said the effort will attract attention from large tech companies that have the capabilities to move quickly.

“We’re confident it will get everyone’s attention,” he said. “It’ll be seen as a real big bet by specialty crops.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Research commission doubles investment in technology

Over the next five years, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission plans to double its spending in the technology arena, said Executive Director Ines Hanrahan.

By raising the tech budget from about $300,000 to $600,000 annually, the commission will be able to fund more research projects approved by the technology committee, support the Smart Orchard project that’s evaluating sensor-driven management, and partner with two broad innovation initiatives, Hanrahan said.

When the commission was founded in 1969, one of the primary goals was to drive labor-saving technology. “Here we are 50 years later, and we are still trying to figure out the labor piece of the puzzle,” said board member Jeff Cleveringa.

But the timing is right for the tree fruit industry to take advantage of emerging technology opportunities, he said. Ag tech companies have solved most of the needs of row crop growers and seem ready to tackle the special tech needs of specialty crops.

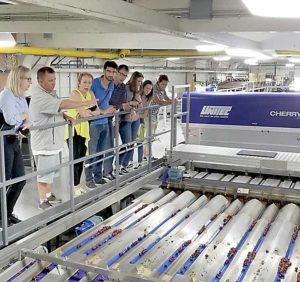

February was a big month for collaboration announcements. On Feb. 3, Washington state and the Netherlands signed an agreement to work together on orchard technology innovation through public-private partnerships. One project, Fruit 4.0, will invest in four areas of tree-fruit innovation: sensing, data management, automation and orchard design.

The research commission committed $60,000 a year to the three-year project, with primary funding coming from the Dutch government, she said. Other partners include the Washington State Department of Agriculture; Washington State University; Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands; FME, a Dutch company that facilitates public-private partnerships in technology development; and several private companies.

“We’re looking for more interested volunteers and any companies that want to collaborate, because ultimately, the goal is to provide solutions to growers by combining research with collaborators to drive innovation to the future,” Hanrahan said.

Then, on Feb. 11, Hanrahan participated in Western Growers’ launch of its new harvest automation initiative, which aims to accelerate tech development for all specialty crops by supporting development of shared platforms and technologies.

“This will help us leverage our funding sources in the best possible ways to bring technology to our orchards,” Hanrahan said.

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment