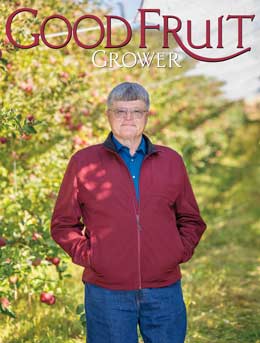

Mike Robinson, the 2021 Good Fruit Grower of the Year, thinks soil is misunderstood and wants the industry to study it more.

The research world has made strides, but he still does not believe anyone — growers, field representatives or scientists — can correlate a soil sample with a tree fruit production result. That frustrates him.

“The answer is out there,” said Robinson, president of Double Diamond Fruit in Quincy, Washington, and one of the leading proponents for Washington State University to use funds from the tree fruit industry’s $32 million endowment to hire a soil ecologist. The goal is to set up a research program to answer such questions.

Robinson served on the search committee for that position. Twice they made offers to candidates, only to be declined. Earlier this year, the university decided to table the soil position search, but they likely will try again in 2023, said Scot Hulbert, the associate dean of agricultural research.

They aimed to place the soil scientist in Prosser, home of WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, Hulbert said. Robinson favored allowing the candidate to set up shop at the main campus in Pullman if it made the difference between the person accepting or not.

“I would have put them wherever we need to put them,” Robinson said.

The sticking point is a common one, Hulbert said. Scientists who qualify for an endowed position are among the top three or four in their field in the entire world. Often, their spouses would seek university jobs as well, which are even harder to come by at field campuses such as Prosser.

Soil frustrations

For years as a field representative, Robinson was taught to take soil samples whenever growers had a question. So, he did. By the thousand, he estimates.

But the tests only studied chemistry, not biology. More importantly, he never could deliver an answer that mattered to tree performance.

“The soil thing bugged me as a fieldman,” Robinson said.

However, as a mission, understanding soil is gaining traction these days.

The Washington State Legislature recently allocated $2.1 million per year to the Soil Health Initiative, a long-term partnership between WSU, the state Department of Agriculture and the state Conservation Commission. In October, the university released a 124-page “road map” to outline current challenges for soil health in Washington, beyond conventional standards based on Midwestern row crops, and show pathways to solutions.

Specifically toward tree fruit, Robinson considers work by Tianna DuPont, a horticulture specialist at WSU’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee, and Mark Mazzola, a former U.S. Department of Agriculture soil scientist, a step in the right direction.

“Tianna has done some good work,” he said. “She’s on the right track.”

Most recently, Robinson and his partner in BMR Orchard, Jim Baird, collaborated with DuPont and Mazzola on trials that began in 2017 on commercial-scale applications of two soil fumigant alternatives — mustard seed meal and anaerobic soil disinfestation.

Robinson and Baird inspired the project and were heavily involved with implementing it, DuPont said. They worked in the field with the researchers, calibrating seed meal applications, figuring out plot plans and operating equipment. The two continue to help the researchers collect data.

“Few partners I have worked with have put so much effort into a project,” DuPont said.

Results have been mixed so far. It’s too early to tell with yields, though both treatments altered the soil microbe population in the rootzone compared to fumigation. As for tree growth,the mustard meal treatments resulted in similar or greater results than fumigation at all three study locations, while the anerobic approach performed better than the fumigated control at three of the four sites.

Robinson had hoped to see the alternatives outperform fumigation more significantly in his own orchards, but he likes the research trajectory. Meanwhile, the grower’s passion for soil science shows, Dupont said.

“Mike pushes us to look at the connections between soil and the bottom line (fruit yield and quality),” she said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment