Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Farmers often joke that there’s no such thing as an average growing season.

So why should they rely on a standard calendar for pest and disease control?

“How weather plays out over an extended period of time can really alter how vines are developing and when they are potentially susceptible to infection or invasion by pests and disease,” said Michelle Moyer, viticulture extension specialist at Washington State University. “So, when you rely on a calendar-based program or think about pest management on a calendar basis, we sometimes miss opportunities, or we sometimes miss critical windows.”

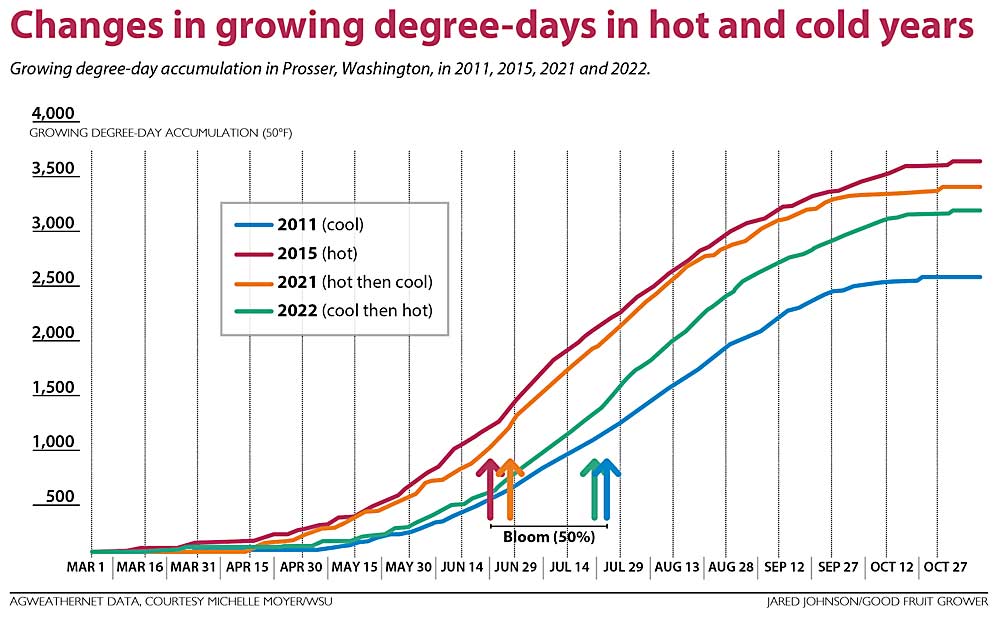

The previous two vintages, 2021 and 2022, present case studies in how different weather conditions can impact vineyard management, Moyer said in a presentation at WineVit, the annual convention held by the Washington Winegrowers Association, in February. Specifically, she focused on disease management.

Take powdery mildew. Or leave it. In the heat of 2021, it didn’t pose much of a challenge.

“It’s the Goldilocks fungus. It likes everything to be just right,” Moyer said. The fungus thrives between 65 degrees and 85 degrees Fahrenheit, and it shuts down around 95 degrees. “So, when we start to hit that July period, Mother Nature can help us control this disease.”

But in 2022, cool spring growing conditions stretched into summer, and most growers probably had to spray for powdery mildew twice as often as the previous season to keep it under control, she said.

When it comes to the two other fungal diseases Eastern Washington growers face, botrytis bunch rot and sour rot, weather usually favors one or the other.

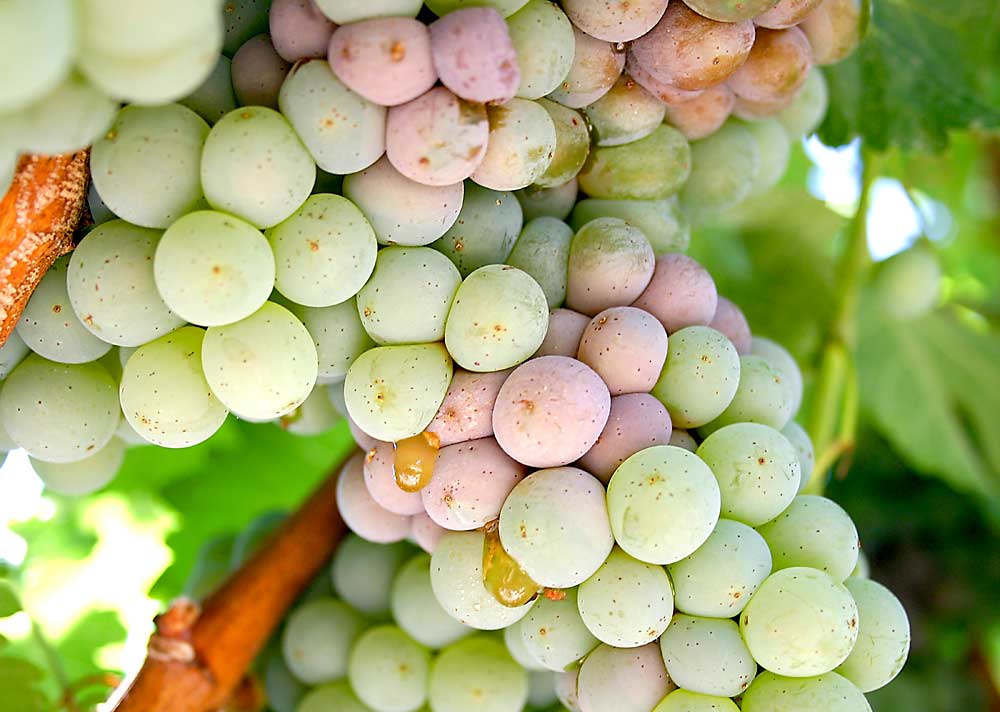

Botrytis, caused by gray mold, starts to become a problem at veraison, because it loves sugar and cooler, wetter conditions. “This tends to be a problem when we have cooler, wet falls,” Moyer said. “When we’re having hot, dry falls, we get the other bunch rot.”

That would be sour rot — a complex of yeast and bacteria spread by fruit flies, which can proliferate when fruit is ripening in warmer, drier conditions.

“You don’t usually see it in clusters until they hit about 15 Brix. If there’s any kind of wounds, those wounds are colonized by these microbes. They start to ferment the fruit, and that attracts fruit flies,” Moyer said.

Management requires both insecticide for the fruit flies and antimicrobial for the microorganisms — at veraison. Timing matters. Two sprays (of a combination of products) at 16 Brix and 20 Brix can provide control equal to applying four sprays throughout the ripening period, Moyer said.

As for botrytis, although it doesn’t show up until fruit ripens, the key treatment window is much earlier.

“While it expresses itself late-season, you really want to reduce the potential for colonization at veraison time period, so you start managing it during bloom time period,” Moyer said. “Some key sprays at the time you are spraying for powdery mildew will give you major control unless you have a lot of rain.”

Last spring did deliver a lot more rain — and snow — than normal, said Yun Zhang, a viticulturist for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates. She spoke after Moyer and shared how the team adapted vineyard management practices to the growing conditions.

“I thought last year was going to be another 2011,” Zhang said, referencing the coolest vintage Eastern Washington has experienced in recent memory. By late summer, warmer weather helped push 2022 up above average in terms of growing degree-days, but the slow start changed a lot of management practices.

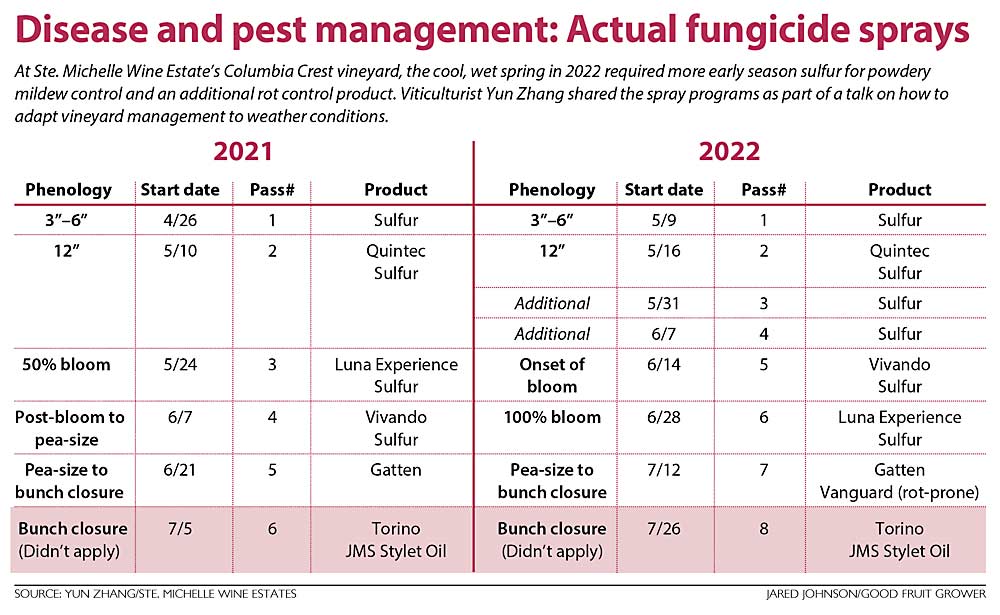

To illustrate that point, Zhang walked the audience through her fungicide programs at Columbia Crest Vineyard in Paterson, Washington, for both years.

In 2021, phenological development was “rather compact,” and each stage and subsequent spray need was spaced a textbook 14 days apart, she said.

“We didn’t need to use our sixth fungicide because we had no powdery mildew infection and the weather was hot,” she said.

Last spring, everything was later. And longer.

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

“We particularly wanted to use Luna Experience at 100 percent bloom because that’s the first critical window to manage botrytis, and Luna Experience is a dual-purpose fungicide,” Zhang said. “But after we put out our Quintec pass, we quickly noticed that — oh no — the bloom is not going to happen in the near future,” she said. So, they decided to put on another pass of sulfur. And another seven days later.

Once bloom began on June 14 — almost a month later than 2021 — it was clear it would be a long, slow bloom, too. So, they made another change and applied the Vivando (metrafenone) first, holding the Luna Experience (fluopyram and tebuconazole) for full bloom. Lastly, they applied Gatten (flutianil), with Vanguard (cyprodinil) for tightly clustered varieties.

She also tried a new botricide, Elevate (fenhexamid), in limited acreage in the high-risk varieties of Sauvignon Blanc and White Riesling, where she saw signs of rot.

“At the end, we didn’t have any outbreaks. In September, weather was very nice to us and it seemed that botrytis stopped spreading,” she said. That was great news but didn’t help her evaluate Elevate’s effectiveness.

The wet spring also drove vigorous canopy growth, plus there were a lot of latent buds pushing. Knowing this thicker canopy would encourage botrytis growth, Columbia Crest Vineyard starting leafing at the onset of bloom.

That provided one more bonus, Zhang said: “By doing the early leafing, we finished leafing before it got hot, so we were not worried about sunburning fruit when summer finally came.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment