The vines were 30-plus years old and declining. Multiple harsh winters had left them with weak, short canes and sections of blind cordon. Yields were low.

And the grower didn’t like the variety, anyway.

“That block had to be pulled,” wine grape grower Chip Dobson said of his aging Merlot block at Rosebud Vineyard in the Wahluke Slope of Central Washington.

But if he had wanted to extend the life of that block, two researchers came up with some tools he could have used. Namely, he could have left the old cordon in place and retrained three short canes from each vine, horizontally, to become the new cordon.

That strategy wouldn’t be as good as replanting, but it would boost yields without missing a crop and maybe extend the life for another five or 10 years, said Hemant Gohil, a Gloucester County agent for Rutgers University’s Cooperative Extension in New Jersey.

“You really should replant,” Gohil said. “This is a temporary strategy.”

At the request of the grower and Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, Gohil led a three-year project comparing methods to rejuvenate a Merlot block declining due to repeated cold injury when he was a researcher at Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center near Prosser. He worked with Markus Keller, a viticulturist at the research center.

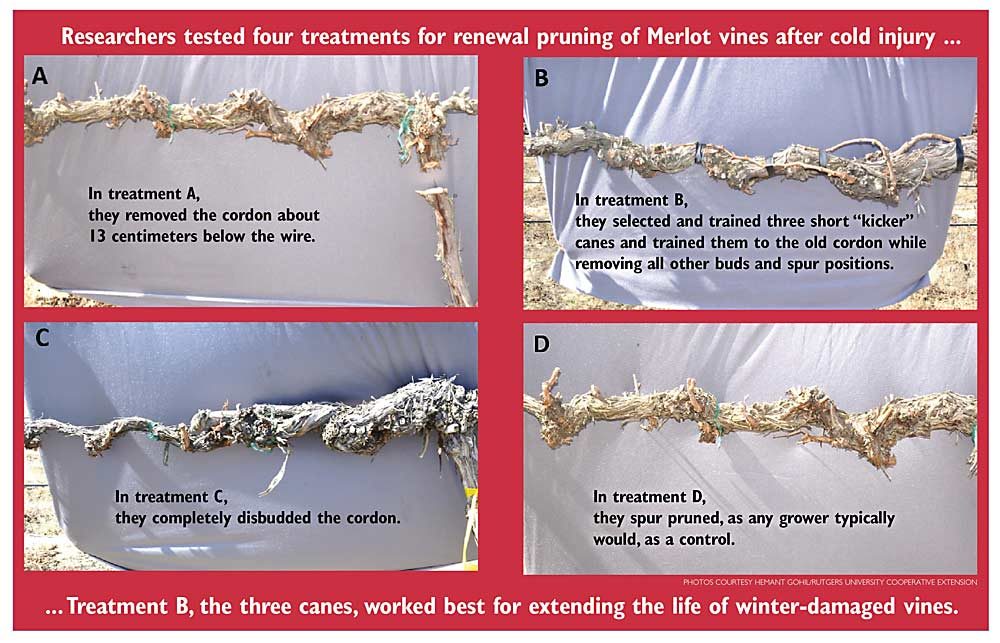

They tried four treatments.

A. Remove the cordon completely, retraining canes from the ground up. Most growers do that with severe cold injury, a method that works best over large areas, not a patchwork of damage that has accumulated over time.

B. Train three canes from each vine into a new cordon. Each cane had between five and 10 buds each. They called them “kicker canes.”

C. Completely disbud the cordon, pushing the latent buds under the trunk and renewing the spur locations.

D. Standard spur pruning, which growers do every year. That served as the control group.

By most measures, the three-cane method worked the best. Differences were large, but clusters per vine and yields were highest with the three canes after three years. And, the method does not cost growers a crop from that vine. The training can be done in winter or early spring and harvested that fall.

Replanting and starting over is still the best idea, when possible, but the three-cane method may provide a way for growers to postpone that decision, the researchers concluded.

“This is not going to revive the block for another 20 years,” Keller said, “but it could buy them five years or maybe 10 years until they’re ready to replant.”

The work was done from 2014 to 2016. Gohil and Keller published their results in October 2018 in “Catalyst: Discovery into Practice,” a journal of the American Society for Enology and Viticulture. Merlot happened to be the variety in the study, though Gohil and Keller suspect the results would be similar for others.

Dobson’s vineyard may be gone, but Gohil has been spreading the message of the project in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and he plans to make presentations in Michigan, New York and Canada. In the Northeast, vine injury due to cold weather and abrupt temperature fluctuations is a routine part of winter compared to the relatively mild climate of Central Washington. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment