It goes without saying that the 2024 increase to the H-2A Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) is the latest in a series of gut punches for tree fruit growers in the Pacific Northwest. With Washington and Oregon growers facing a 7 percent increase and Idaho growers facing a 5.4 percent increase, these new wage rates will threaten the ability of many to continue to farm.

What is the AEWR and why is it so high?

When Congress wrote the law that created the H-2A program in 1986, they included a provision to require that domestic workers were not “adversely affected” by the presence of H-2A workers in the United States. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) developed the AEWR — using data from surveys that were conducted by other federal agencies and not intended for this purpose — as the mechanism to fulfill this statutory requirement.

We did not arrive at a $19.25 AEWR in Washington and Oregon, and $16.54 in Idaho, overnight. Unfortunately, the writing has been on the wall for years spelling out that the flawed methodology used to establish the AEWR would eventually result in a wage rate unsustainable for tree fruit growers — a place too many have already reached.

For more than two decades, the Northwest Horticultural Council (NHC) has hammered home this message to Congress and pressed for legislation to revise how wages are set within the H-2A program. These efforts include working directly with Congress, and in collaboration with allied groups, to pursue solutions that are commercially and politically viable. We also engage with DOL and other federal agencies to influence regulations.

While we have gotten close on a few occasions, Congress has never been willing to do what it takes to get reform across the finish line.

There is no question that the politics are tricky. Very few members of Congress represent predominantly agricultural areas, and even fewer represent areas where labor-intensive agriculture is king. In what is perhaps the biggest hurdle, in the eyes of many members of Congress, this issue falls under the umbrella of immigration and border security — a lightning rod of controversy with voters and within Congress.

Ultimately, we need reform that makes the H-2A program sustainable for growers of all sizes and provides a pathway to legalization for undocumented members of the current workforce. Some agricultural groups (primarily representing areas with wage pressures far lower than ours) have insisted that no bill should pass Congress unless it is perfect for employers. However, the NHC and many of our allies on this issue believe that a bipartisan solution is the best chance at success in addressing our industry’s labor needs. The legalization provisions bring Democrats to the table, while an E-Verify requirement and H-2A reforms are attractive to Republicans. We continue to make the argument that all Americans are impacted by this issue because of the threat to food security.

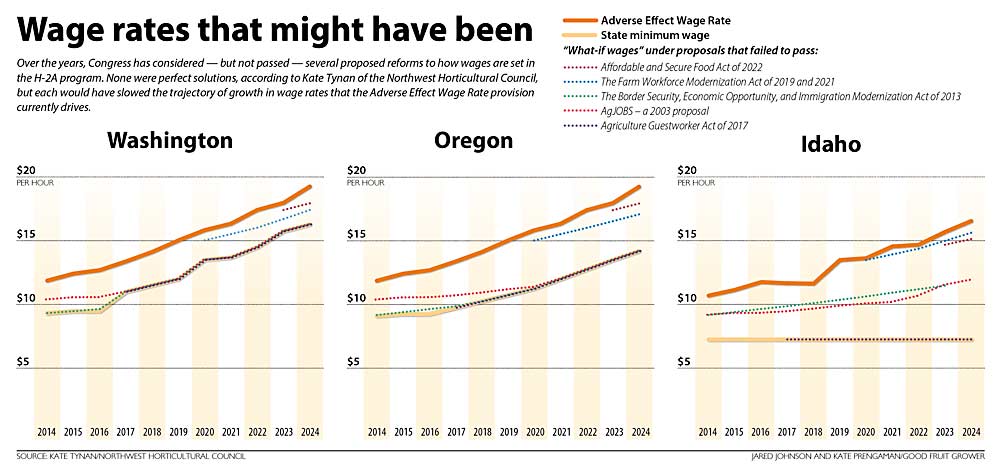

While this approach is our best option in a polarized Congress, it also has required agricultural interests to negotiate with farmworker unions. The resulting legislative proposals have been far from perfect. However, if any of those past proposals had been implemented, we would be in a much better place today.

For example, the NHC supported the AgJOBS bill that gained some traction in Congress in 2003 and the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act that passed the Senate in 2013. If either of these bills had been signed into law at the time, Washington and Oregon growers would have been required to pay the state minimum wage in recent years, because it would be higher than the AEWR-equivalent wage rate. The required wage for Idaho growers would be 28 or 30 percent less, respectively, than what is currently mandated.

The NHC also supported the Agricultural Guestworker Act in 2017 — a Republican-only bill that we hoped would be a negotiating point with the Democrat-controlled Senate. Had it been signed into law, growers in Washington and Oregon would be required to pay the state minimum wage, while Idaho growers would be required to pay a minimum of $8.34 this year – a little over half of the current AEWR.

If the Farm Workforce Modernization Act (FWMA) — negotiated by Washington’s own Rep. Dan Newhouse — had been signed into law in 2019, the AEWR would be $17.41 in Washington, $17.08 in Oregon (based on the standard minimum wage), and $15.61 in Idaho. A version of this legislation introduced in the Republican-controlled Senate in 2022, but never acted upon, would have resulted in an AEWR of $17.93 in Washington and Oregon, and $15.12 in Idaho this year.

A couple of important caveats: First, as all growers know, the minimum wage set within the H-2A program is the base wage. Market dynamics often mean that growers are paying a higher wage rate to many workers. Second, several of these bills maintained some sort of prevailing wage structure — so depending on the methodology used to develop that prevailing wage, wages may have been higher than what is reported in some years — particularly in Washington.

The news isn’t all bad. The political dynamics have improved significantly since the early 2000s. AgJOBS wasn’t even able to get a vote in Congress. The 2013 bill passed the Senate with bipartisan support. The FWMA passed the House with bipartisan support twice — in 2019 and 2021.

It is important to note that every member of the Pacific Northwest congressional delegation supported the FWMA in 2019, spanning from Rep. Pramila Jayapal, who represents liberal Seattle, to Rep. Russ Fulcher, who represents the most conservative region of Idaho. (Fulcher did not support the bill when it passed in 2021 because it did not include border security provisions.)

This brings up a second important point: Even with support from the entire (or nearly so) Pacific Northwest House delegation, agricultural workforce reform efforts still failed to become law in 2019 and 2021. This is why the NHC has made it a priority to work with groups representing growers in other parts of the country, to influence both substance and advocacy strategy.

Pacific Northwest tree fruit growers seem to be the poster child for where the rest of labor-intensive agriculture will find itself in the future if the AEWR is not reformed — a critical story to get out to policymakers nationally.

With intense congressional dynamics, very close margins and a key committee chairman in the House hostile to H-2A reform, the odds are stacked against us even more than usual in the current Congress. The NHC continues to believe that the best outcome for growers is broad reform, as outlined above, and we are pushing for such policies. However, we also recognize that such efforts are not likely to be successful in time to help growers grapple with this most recent AEWR increase. Therefore, the NHC is also advocating for immediate relief by freezing the AEWR at 2023 levels for 2024. We are working diligently to attach this language in a “must pass” bill funding the federal government. A final decision by Congress is expected by mid-March.

This is not an issue Congress will take up unless we force them to. We must continue to shout from the rooftops to our elected representatives that the growth trajectory of the AEWR is driving growers out of business, and the longer Congress takes to address this issue, the fewer growers will be left standing.

—by Kate Tynan

Kate Tynan is the senior vice president of the Northwest Horticultural Council. Based in Yakima, Washington, the NHC represents the growers, packers and shippers of apples, pears and cherries in Washington, Oregon and Idaho on federal policy.

Leave A Comment