Pruning is the most important task in the life of a vineyard, and doing it well takes a lot of time and attention, said Michigan State University viticulture professor Paolo Sabbatini.

Mistakes made during dormant pruning can be costly, forcing growers to spend the rest of the season correcting them. Sabbatini recommends holding off on dormant pruning until March, to avoid cold damage in pruned areas. For Vitis vinifera varieties, March also is a good time to assess winter damage.

When those traditional European cultivars were first planted in Michigan about 50 years ago, growers used the concept of “classical balanced pruning” — the idea that you need to leave a certain number of buds on the vine in relation to pruning weight. This was helpful for new grape growers who didn’t understand the interactions between soil, cultivar and rootstocks on their virgin sites.

After half a century growing vinifera in Michigan, however, growers now know their soil, variety and rootstock interactions pretty well and understand how to tailor their pruning techniques to specific vineyard needs. They also know approximately how many buds they need to leave on the vines to reach their target yield, Sabbatini said.

Michigan’s grape-growing season is cool and short, and its yields are low compared to warmer wine regions. Low-yielding vines tend to be too vigorous. Sabbatini recommends pruners reduce vigor by leaving weaker canes on the vine.

“Cane selection is very important,” he said. “Make cuts to select canes you think will carry fruit, but not a lot of vegetation.”

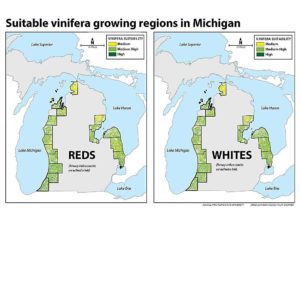

Most of Michigan’s vineyards stretch along the Lake Michigan shoreline, where the big lake’s moderating effects offer some protection from extreme temperatures. Further inland, vinifera especially struggles to stay productive.

Stoney Ridge Vineyards in Kent City, Michigan, sits on the Fruit Ridge, an area north of Grand Rapids best known for its apple production. The vineyard has about 4 acres of grapes, mostly University of Minnesota cold-hardy hybrids, as well as some Chardonnay, which — being vinifera — struggles in the area, said vineyard manager Kip Weinberger.

During winter pruning, Weinberger removes about 95 percent of the previous year’s growth. He makes cuts in the direction of the bud. Ideally, he wants remaining buds pointing in a row, with at least 4 inches between each spur, to create an open canopy with as few leaves as possible in the fruit zone.

When pruning, Weinberger assumes each bud will make one shoot, and each shoot will make two or more fruit clusters. He doesn’t want more than two clusters per shoot, and he doesn’t want more than 24 shoots per vine, he said. With more than 50 clusters per vine, it’s harder to ripen fruit to the desired Brix level.

Weinberger generally makes three more passes through the vines during the remainder of the season. When shoots are about a foot long, he removes double-placed shoots on a single node and shoots facing the wrong direction, because they might interfere with the fruit zone. Next, he thins clusters after fruit set. Finally, he pulls leaves and laterals just before veraison.

Along a different Great Lake, the pruning advice looks similar. In the Lake Erie region, pruners should wait until late February or early March to start dormant pruning in vinifera to avoid winter damage, said Jennifer Phillips Russo, team leader of the Lake Erie Regional Grape Program, a partnership between Cornell University and Penn State University.

About 32,000 acres of vineyards stretch along the southeastern shore of Lake Erie, through both Pennsylvania and New York. Most of the vineyards are Concord juice grapes, but about 10,000 acres are wine grapes — a mix of vinifera, hybrid and native varieties, she said.

The main goal when pruning is to prevent undercropped and overcropped vines, which allows for adequate shoot and root growth year after year. If the vines were overcropped in the previous growing season, pruners should remove more buds to bring the vine into balance. If the vines were undercropped, they should leave more buds on the vine, she said.

Spur-pruned vines typically are pruned down to four or five shoots per linear foot of row, with two to three nodes per spur. Some growers leave up to five nodes. Much depends on your production goals, Phillips Russo said. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment