Wine growers around the globe rely on rootstocks to provide pest resistance, control vigor and help them adapt to site conditions. But for Washington growers who have traditionally planted own-rooted vines, now trying to select rootstocks for new plantings in light of recent findings of phylloxera, rootstocks can seem like a bit of a brave new world.

That’s why WineVit, the virtual convention organized by the Washington Winegrowers Association, organized a session focused on rootstocks.

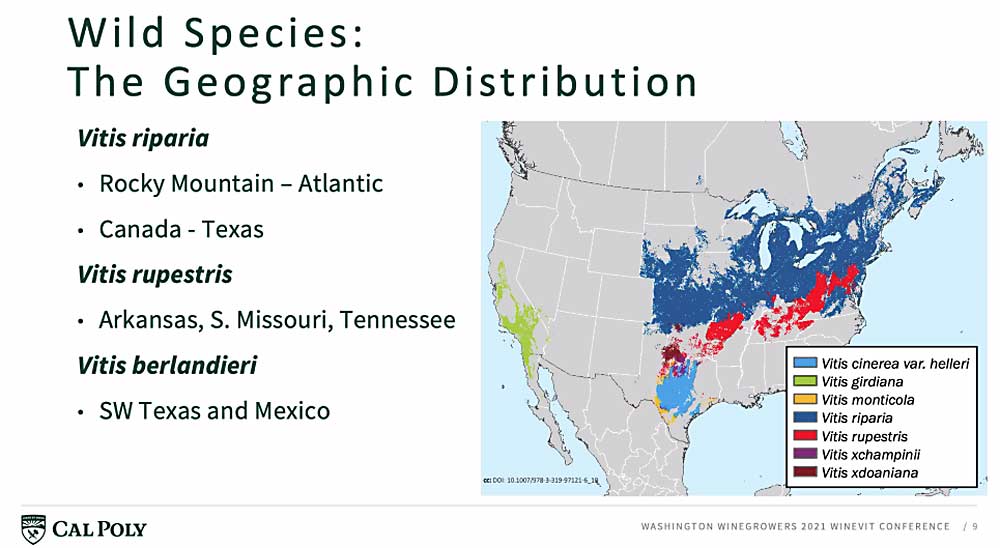

For growers overwhelmed by the new language of rootstocks, California Polytechnic State University viticulture professor Jean Dodson Peterson said it helps to consider the history. Phylloxera, which is native to the Eastern U.S., devastated the French wine industry in the late 1800s after it was accidentally introduced, so breeders turned to the native North American grapes for resistance.

“It’s really important to note here that the majority of the rootstocks released for use were hybrids of Vitis riparia and Vitis rupestris,” Dodson Peterson said. Understanding those grapes’ native habitats helps to understand their performance as rootstocks: V. riparia has a shallow root system, because it’s adaptive to riverbanks and other wet areas, while V. rupresris adapts well to drought and dry farming, since it develops deeper roots.

Those innate traits matter, but rootstocks also adapt to each site, soil and irrigation regime, so it can be hard to translate the data on vigor or drought tolerance from a chart developed in California or from potted plant trials.

“The most meaningful trials are the ones in your own backyard, in your own trials,” Dodson Peterson said. She urged Washington growers to coordinate with neighbors to plan “bite-sized” trials to familiarize themselves with options.

Washington growers may also want to factor nematode resistance into their rootstock choices, said Washington State University’s statewide viticulture extension specialist Michelle Moyer. While extremely sandy soils may protect some sites from developing high pressure populations of phylloxera, those sites are ideal habitat for the northern root knot nematode, she said.

In 2015, she planted a rootstock trial to evaluate resistance to the nematode, as most rootstocks in California are evaluated for resistance against the southern root knot nematode. The species are related, but in Washington, the northern cousin has fewer generations per year, which seems to mean that rootstocks considered to have moderate tolerance to the southern root knot nematode perform quite well against the northern nematode, Moyer said.

“When you grow a grapevine on a rootstock, there are varying levels of tolerance. Some will not support the pest at all, others will support some feeding because they are very vigorous,” she said.

In additional to her nematode-focused trial, she shared results from a long-term trial evaluated by WSU viticulture professor Markus Keller and winemaker Jim Harbertson. They found that while grafted vines may show slightly less vigor than own-rooted vines under the same irrigation regime, rootstocks had no impact on fruit quality, Moyer said.

Another speaker, Jason Magnaghi, a viticulturist for Figgins Family Wine Estates in Walla Walla, echoed that. He first planted grafted vines in 2002 because of a nursery order mix-up: Those were the vines available, and it seemed like a good learning opportunity.

“The wines are just as good, no question,” he said.

From a viticulture perspective, he found that different rootstocks may need different irrigation regimes — up to 30 percent more water for Riparia Gloire, for example — but he plans to put that variation to use, planting that rootstock at a more vigorous site, for example.

Moyer said that while rootstocks do offer different beneficial traits beyond pest control, those traits are just a part of the vineyard’s management. Growers may have to adapt irrigation practices, but not overhaul the way they farm, she said.

“Rootstocks have influence, but not more so than cultural practices,” she said. “They are a tool we can use for long-term sustainable management.”

According to a poll taken during the session, many growers are concerned about the increased risk from cold damage — grafted vines are not more cold-susceptible, but if they do suffer a killing freeze, they can’t be retrained from the roots. Regrafting is expensive.

Moyer said the common practice is to hill up over the graft union in the fall — so the soil insulates the scion — and dehill in the spring. Some growers worry this practice can result in scion rooting, but that only occurs if they don’t dehill sufficiently, she said.

Magnaghi also uses cane burial as a hedge against cold damage across all his vineyards, grafted or own-rooted. At $500 an acre in labor costs, he acknowledged that it’s an expensive form of insurance.

Given the phylloxera pressure in the Walla Walla area, Magnaghi said his future plantings will all be on rootstock now, and he’s grateful for the accidental experience in farming them.

He advised growers overwhelmed by selection decisions that the best thing they can do is “have a really good relationship with your nursery.”

Dodson Peterson stressed that growers shouldn’t be afraid to ask questions and plant small-scale experiments.

“I hope this has ignited an interest in you to explore the rootstocks that are available to you,” she said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment