Grower Dick Boushey believes the biggest effect on Cabernet quality comes from the weather. “Wherever it’s grown, it has to be fully ripe when picked,” he says. Marcos Zambrano harvests Cabernet Sauvignon near Benton City, Washington on October 10, 2014. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

In a warm vintage, wine grape growers can step back and let the vineyard do its thing, says Dick Boushey, who grows grapes in Washington’s Yakima Valley and Red Mountain. But in a cool growing season, the timing of viticulture tasks is everything.

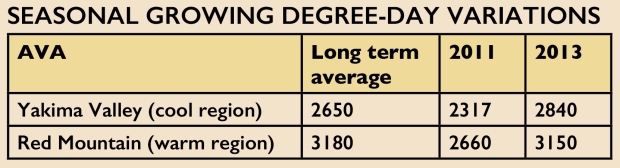

Vintage variation is what makes wine unique and unlike other beverages. But big swings from year to year in growing degree days, also known as heat units, creates challenges in the vineyard and winery and requires know-how in coaxing the best out of the fruit.

Washington’s wine industry shared lessons from the cool 2011 and warm 2013 vintages during the annual convention sponsored by the Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers. Vintage variation, which occurs more frequently in cool-climate grape growing regions, was apparent in wines sampled during the session from the 2011 and 2013 vintages. The session focused on Cabernet Sauvignon, a sun-loving variety and one that is most impacted by cool seasons.

Boushey, who’s been growing grapes in Grandview since 1977, is responsible for 225 acres of his own and managed vineyards on Red Mountain. “I used to think that cool-climate viticulture didn’t really apply to Washington, but 2010 and 2011 were definitely cool climate vintages that required a different approach to viticulture,” he said. He doesn’t even like talking about 2011, and says it’s like a tragic event he tries to block from his mind.

“In 2013, you just needed to get out of the way and let nature take its course,” he said, adding that bloom was early for Cabernet Sauvignon, not much rain occurred at harvest, and there were “wonderful heat units.”

But in 2011, bloom and veraison were two weeks behind normal, disease pressure was high, harvest was compressed into just a few weeks, and the state produced only about half the tonnage of Cabernet as in 2013. “It was a great year for white varieties, but reds were really challenged,” said Boushey.

No room for error

The biggest lesson from 2011 is that in cool vintages, there’s no room for error. In cool seasons, growers must react quickly, do things early, and carefully manage water and nutrition.

The cool vintage emphasized the importance of choosing the right site for Cabernet Sauvignon and underlined the notion that wine is made in the vineyard.

Dick Boushey

Though Merlot, Syrah, and Riesling do well in most Washington AVAs (American Viticultural Areas), Cabernet Sauvignon needs to be in the right spot with the right temperatures.

“It does best in poor, deep, gravelly soils and needs high elevation and warm temperatures,” Boushey said. “We need great sites with long growing seasons for Cab for when we get hit with these cool years.”

While Cabernet Sauvignon needs a balanced canopy and crop load and careful management of nutrition and water, Boushey believes the biggest effect on Cabernet quality comes from the weather. “Wherever it’s grown, it has to be fully ripe when picked.”

In cool years, Cabernet fruit is often described as having notes of green pepper, herbs, and fresh green tea leaves, he said. “But that’s not what consumers want. They want flavors of ripe blackberry and currant.”

When it comes to green notes, he says it comes back to the vineyard—delivering ripe Cabernet to winemakers falls on the grower. “Methoxypyrazines, (the chemicals responsible for green flavors in wine), are like the canary in the mine because their presence can indicate immature fruit, lack of color, and harsh tannins.”

Toolbox

Boushey shared four things that can help growers deliver quality fruit to the winemaker: pruning, historical crop data, water management, and pest and disease control.

1. Pruning. Pruning should be done in a timely and consistent manner. Late pruning can delay bud break, not a good thing in a cool year. Leaving too many buds can result in vine stress from overcropping, while too few buds can produce unbalanced vines and lead to vegetal characteristics in wines.

He prefers leaving extra buds in case of a poor set. “Plus, you then have the option later of dropping fruit and using fruit as a sink for vigor.”

2. Water management. In cool years, water management is the most important tool growers can use to impact the crop. “Overwatering is undesirable, especially in a cool season,” he said. Using water in moderation early, between fruit set and veraison, allows later irrigation if necessary.

He avoids high soil moisture at pre-and post-veraison because it delays the degradation of methoxypyrazines. Most growers in the state use regulated deficit irrigation strategies and apply less water than the vine is using to help control canopy growth. Research shows that applying a deficit in red varieties before veraison, as well as after veraison, results in smaller berries.

3. Historical crop data. Boushey keeps with him at all times historical crop data (dates of past bud break, bloom, veraison, and yield data) so he knows what kind of growing season is under way. “You need to have that data with you all the time so you can compare year to year. In a cool season, you need to make things happen quickly or you will pay the price.”

4. Disease and pest management. Disease pressure tends to be higher in cool years, especially if higher rainfall comes at bloom and harvest. He applied three more fungicide sprays in 2011 than in 2013. In warm years, temperatures often rise above—at least for some of the season—the active stage for powdery mildew, however, warmer temperatures can give some insects an earlier start and time to develop through an additional generation.

Crops grown in cool years often are more expensive because they require more labor and sprays. Boushey noted that in 2011 he made three thinning passes to get clusters to the same maturity and put on three more fungicides than in 2013.

Because light exposure has been shown to help to reduce methoxypyrazines, he removed leaves early in 2011, first on the east side in the fruiting zone and then later on the west side so that clusters were well exposed. He believes leaf removal made a key difference in his fruit quality that year.

Basal leaves were also removed because methoxypyrazines are said to accumulate there. In 2013, he was concerned about sunburn and only partially leafed on the west side.

Flavors in the fruit eventually came in the 2011 vintage, though slowly. Fruit was harvested in early November, just as winter weather was coming. He did a lot of handholding with nervous winemakers during harvest.

“It was a very intense and expensive year,” he said of the 2011 vintage. “We spent so much time in the vineyard that few growers made money.”

But it turned out to be a good vintage for many wines—wines that Boushey is proud of. He has received compliments from a winemaker who loved the wines that came from Boushey’s fruit.

He says the cool year made him a better grower and his crew better. “Ultimately, we showed the rest of the world that even in a cool vintage, we are skilled enough to work through the challenges.” •

———-

Vintage differences

David Forsyth

David Forsyth, director of winemaking at Zirkle Wine Company in Prosser, set the stage for comparing the 2011 and 2013 vintages.

Yield in 2011 of 142,000 tons was down 15 percent from the previous year due to an early freeze in November of 2010. Statewide production in 2013 at 210,000 tons was considered a normal crop. The increase in tonnage primarily reflected new plantings, said Forsyth.

Cool temperatures in 2011 during bud break resulted in reduced and uneven fruitfulness that delayed harvest by at least two weeks.

The low overall heat units resulted in fruit with lower Brix than normal and higher acidity levels. In 2013, early varieties were harvested ten days ahead of normal, though later varieties were picked at normal times. Fruit had normal Brix levels but lower acidity.

Growing degree days are the number of degrees Fahrenheit over a base temperature of 50°F accumulated daily during the growing season (April 1 to November 1). Source: David Forsyth from Washington State University’s AgWeatherNet

Leave A Comment