More scientists are examining the complex relationship between plant roots and soil microbes, but there’s still a lot to learn — especially about the effects on plant health.

So far, we know that a root’s function and location greatly influence its interactions with soil microbes — whether they’re “good” microbes (from a fruit grower’s perspective) like mycorrhizae or “bad” microbes like phytophthora.

A root might attract microbes because it has a greater source of carbon, for example, or because it occupies a particular space. Individual roots play a role in the number and kind of microbes attracted to a root system. The soil’s role as a feeder source for microbes also factors in, said Suzanne Fleishman, assistant professor of root biology at Penn State University.

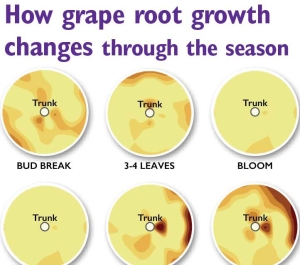

Fleishman studies the relationship between grapevine roots and soil microbes, including the impacts of different rootstocks and cover crops. Cover crops can have different effects on the root microbiome. Also, grapevines shift their roots deeper in response to groundcovers. In a low-nitrogen vineyard, for example, it’s better to plant a legume instead of a grass because grass competes for nitrogen. Conversely, a grass might work well in vineyards with excessive vegetative growth or those in need of erosion control, she said.

Fleishman is still gathering information about which management practices might aid beneficial microbes, but she said reducing tillage, planting cover crops and adding mulch are good general practices for improving soil health.

“Anything growers can do to improve soil quality will improve good microbes,” she said.

Penn State professor emeritus David Eissenstat discussed Fleishman’s grapevine research, and root/microbe interactions in general, during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market EXPO in December. He said all roots are not functionally equal. They may vary in diameter, in developmental stage, in activity — and they can have entirely different populations of microbes.

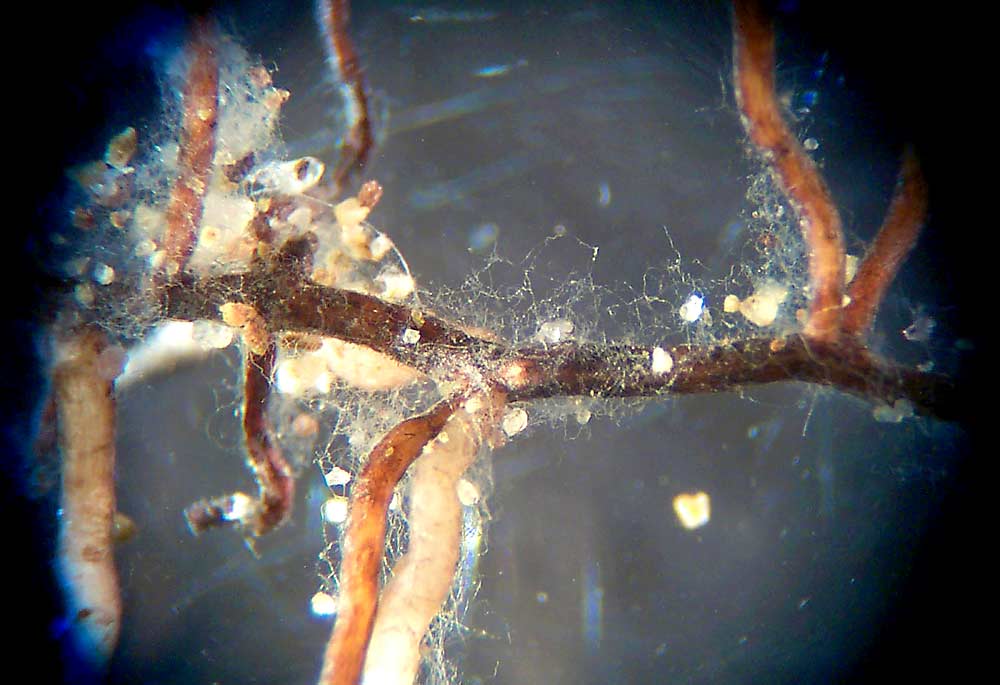

Eissenstat said microbes associated with high-resource environments, such as mycorrhizal fungi, tend to colonize young, vigorous grapevine roots. Other microbes exhibit strong spatial patterning, colonizing some root clusters but not others. Researchers are now using molecular techniques to study the microbial communities around roots.

“We’re just beginning to get our heads around how to look at microbes,” he said.

One of the barriers to this kind of research is that the root microbiome is underground and difficult to observe. It takes substantial time and effort to study such a nonuniform environment, Fleishman said.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment