Jason Deveau, application technology specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, encourages growers to spray smarter to improve pesticide coverage, reduce drift and save some money. (Courtesy Ken Sapsford)

Pesticide labels may define the maximum, safe, per-acre amount for your apple orchard, but they will not tell you how to get the most effective coverage.

It may well be that your orchard can do better with 15 to 25 percent less product, according to Jason Deveau, an application technology specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). He is on a mission to get growers to reconsider their pesticide practices.

Deveau is behind OMAFRA’s free app called OrchardMAX and also co-publishes a website called Sprayers101.com — both designed to help growers get the most out of pesticide applications.

“I can’t imagine any one thing that orchardists can do in a few hours that pays back as much as crop-adapted spraying does, and the only reason they don’t do it is because they don’t know that they should,” Deveau said.

After four years of trials on three orchards, he said it’s clear that crop-adapted spraying works. “For the trials, we scouted every week and compared this method versus whatever it was that the grower usually did. What we found was that crop-adapted spraying reduced pesticide use by an average 25 percent, and when the growers harvested the apples, there was far less damage on their fruit,” he said.

“With crop-adapted spraying, they weren’t spraying the grass or the air; they were reclaiming that wasted pesticide so they could go further on the tank. And while they were technically spraying less per acre, as far as the crop was concerned, they improved matters.”

He added, “To be clear, this process is about achieving consistent coverage to improve crop protection. Any savings in spray mix is simply a nice bonus.”

Getting started

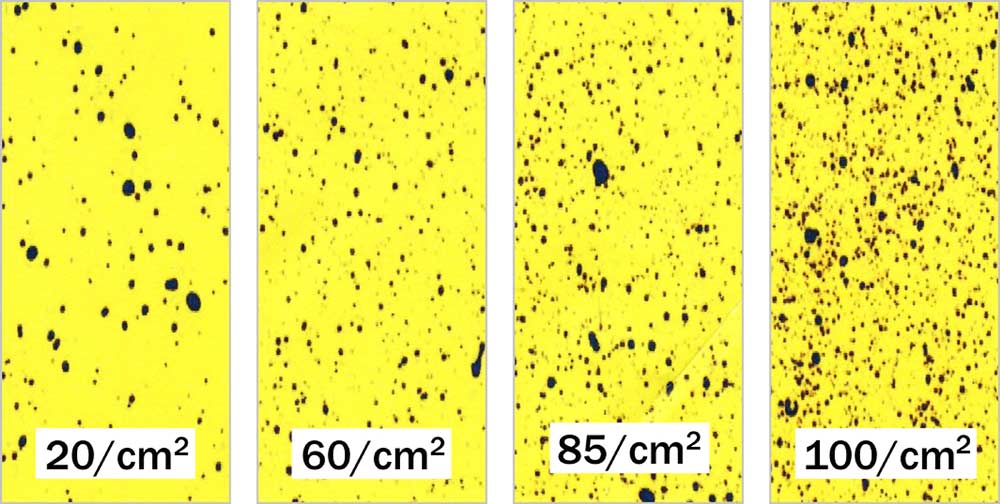

Water-sensitive paper clearly shows whether sprays are reaching every part of the tree. For foliar insecticide/fungicide applications, a reasonable coverage threshold is an even distribution of 85 drops per square centimeter and an overall coverage of about 15 percent. Deveau noted that this “ideal” does not include plant growth modifiers (e.g., stop-drops or thinners) or applications intended to drench the bark. (Courtesy Sprayers101.com)

To implement crop-adapted spraying, he said, all growers need to do is to review their spray practices twice a year — early in the season and again at petal fall — and then make the necessary adjustments to ensure as complete and consistent coverage of their trees as possible.

The first step in the review is to check airflow. Deveau recommended tying a few lengths of strong ribbon on the sprayer air outlet, parking the sprayer in the alley between tree rows and starting up the air. “The ribbons show if your airflow is skewed and indicate where you should set your deflectors (hopefully you have deflectors) to only just over- and undershoot the canopy,” he said.

The next step is to tie three lengths of flagging tape along the height of the far side of an upwind tree. “As you drive down the alley, have a helper watch as you pass the tree to see if those ribbons do anything. You want them to waft a little as you pass,” he said. Ribbons that stand straight out indicate that the air is blowing too hard, and the spray is passing right through the tree, rather than in it.

To get a nice waft, growers will likely have to make a few adjustments.

“Let’s say the ribbons don’t move at all; they’re dead. It could be a number of things,” he said. Adjustments may include moving the sprayer fan into the next highest gear, slowing the driving speed to give the sprayer time to push the air through the canopy, switching to a larger sprayer or pruning some of the density out of the tree. “You just pick the solution that works best for you,” he said.

Once the correct airflow is accomplished, the third step is to check the spray pattern. For this, Deveau folds three 1-inch by 3-inch pieces of water-sensitive paper in half and clips them on a test tree so that one side faces the direction of the sprayer and the other faces away.

One goes near the bottom of the tree, one in the middle and one near the top. If the trees are dense, he adds two more within the tree to check penetration. He marks all the pieces of paper with flagging tape to make them easier to spot and may even label the backs of the papers for later comparisons with other spray passes.

With papers in place, the operator makes one pass on one side of the test tree. “Then you get out and take a look. Did you get to the top of the tree? Yes or no. Did you penetrate to the middle of the tree, which is the goal? Yes or no. Did you hit the bottom of the canopy? Yes or no,” Deveau said. If the pattern is not ideal, adjustments are again the answer.

“This is where you can be creative. If you suspect that the lower nozzle is just spraying ground and the trunk, you might turn it off and see if that makes any difference on the bottommost paper. If the middle of the canopy is not receiving any spray, you may have to raise the rate in those nozzle positions. Poor spray pattern at the top of the tree, which is challenging because it is not only farthest from the sprayer, but is also in a windier spot, may prompt a change to an air-induction nozzle that makes bigger drops that are less likely to be deflected.

“The point is that you’re not just guessing, because the fact of the matter is that you can’t just look at a plume and assume you know where it’s going,” he said.

To make the process as simple as possible, Deveau and spray specialist Tom Wolf, co-owner of Agrimetrix Research and Training and a former spray researcher at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Saskatoon Research Station, collaborated on the Sprayers101.com website.

The site provides details about efficient spraying and also offers the OrchardMax app for free download. The app asks a series of questions about such things as equipment and other spraying practices and then makes suggestions while also maintaining a record of pesticide use.

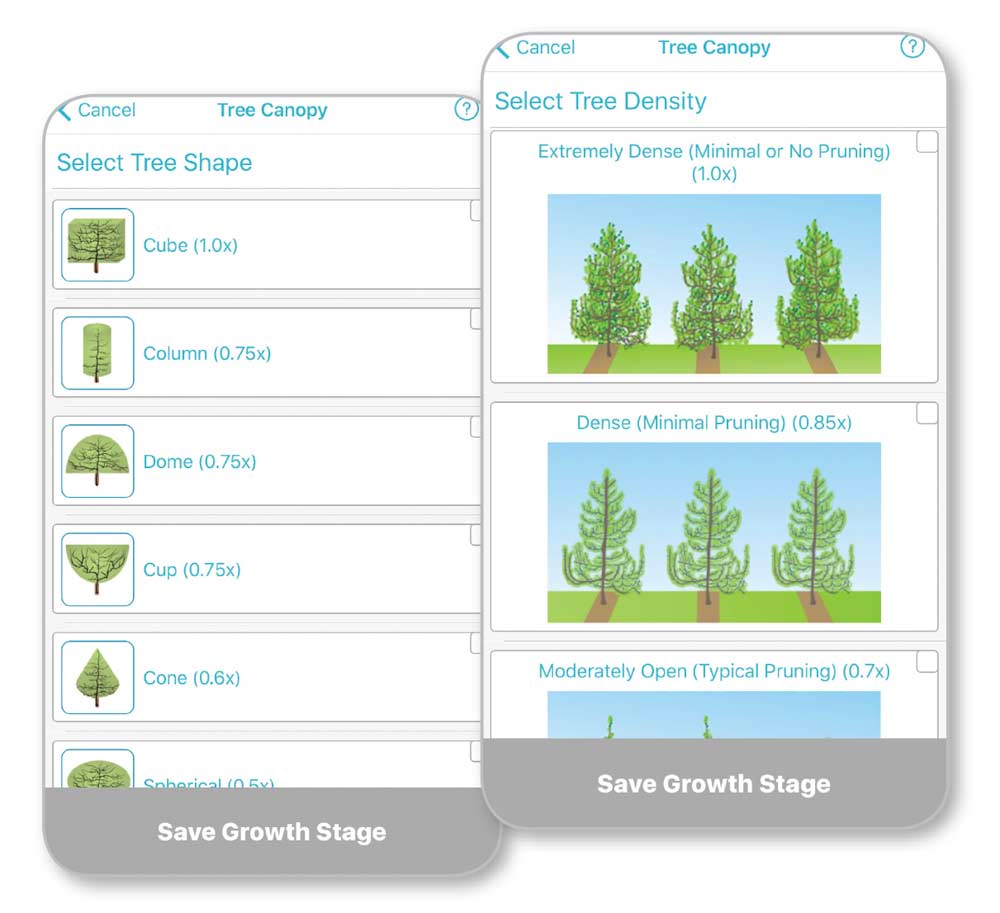

The OrchardMax smartphone app uses grower-input information about the orchard and operation, such as

tree density and shape, and suggests an ideal spray volume right down to nozzle rates. These ideals will still require minor adjustments, as indicated by water-sensitive paper and ribbons. (Courtesy OrchardMax)

Deveau cautioned that the app can only suggest ideal sprayer settings. Growers still must perform the tests with ribbons and water-sensitive paper.

And no matter what tools the grower uses to improve sprayer efficiency, it can make a big difference, Deveau said.

“All the crop-adapted spraying process costs you is some time and a new way to think. Growers who follow the steps are paid back in spades, and payments may be that they save water, they save spray mix, or perhaps they keep pesticides out of a neighbor’s lot or the environment. Most importantly, though, their fruit is better protected.” •

– by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment