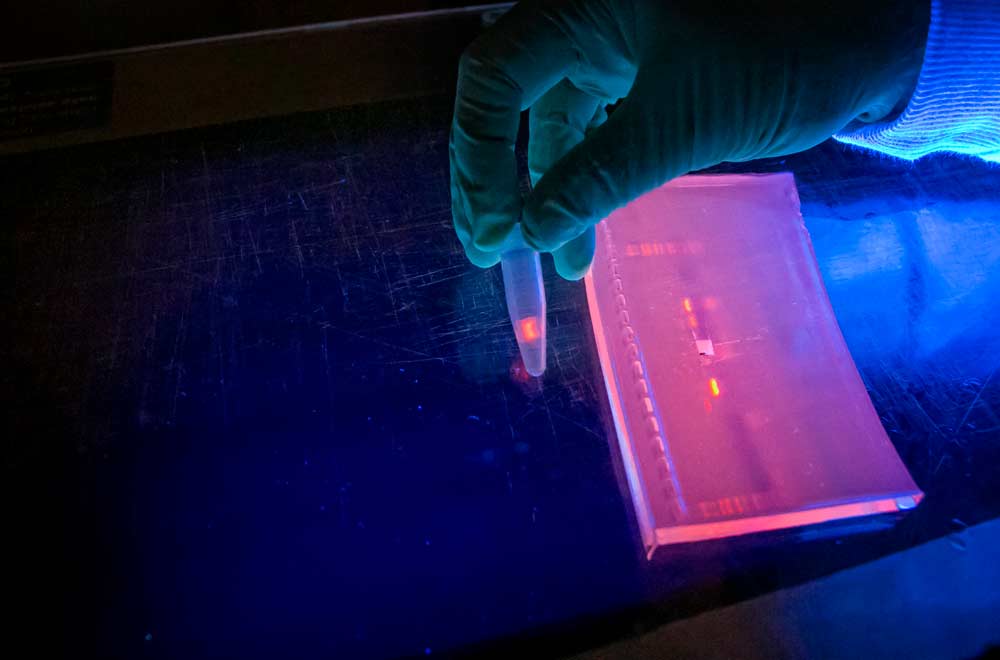

Biological science technicians demonstrate a gel-based method for processing DNA from pear psylla gut contents on Monday, April 24, 2017, at the US Department of Agriculture research laboratory in Wapato, Washington, to help determine where the pests spend their winters. The gel formula helps amplify the genetic sequences, illuminated by black light, to provide enough sample material to study. Researchers have since switched to a PacBio sequencing method that is faster and cheaper. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Rodney Cooper knows at least one thing about pear psylla: They get around.

“The surprising thing to me is just how many different plants they seem to visit when they’re moving around in the fall and in the spring,” said Cooper, a U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologist, who — for the record — knows way more than one thing about the dreaded pests.

Cooper is studying where the psylla spend their winters, figuring that growers would have an easier time controlling the insects if they only knew where to look. To determine that, Cooper is using DNA-sequencing of psylla guts to search for markers from plants they eat.

Here’s why it matters: Psylla nymphs cause russeting streaks and blotches on fruit by dripping honeydew after feeding on the plant material. Also, in large numbers, psylla can stunt and defoliate trees and cause fruit drop. Making matters worse, psylla have been developing resistance to insecticides that worked well in the past.

“While pear psylla has been a problematic pest since its introduction, the past few years have been extremely challenging for psylla control,” said Betsy Beers, a Washington State University entomologist. “Insecticide resistance and insufficient biological control both play a role. We need to get back to the basics of psylla biology, and finding out where they spend half the year is a huge gap in our knowledge.”

Rodney Cooper uses a beat tray and hose to knock overwintering pear psylla from a tree located near the USDA ARS laboratories in Wapato, Washington, on January 8, 2018. Cooper says psylla like to spend the winter in ornamental evergreens, similar to those used in the Pacific Northwest as wind breaks. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Results so far

They’re not done, but Cooper and others at the Agricultural Research Service laboratory in Wapato, Washington, have made a few major findings to fill that gap:

—The concept works. Pear psylla really do eat plants other than pear and their guts really do retain DNA markers of those plants.

—Pear psylla move around — a lot. Researchers found genetic markers from everything from poplar and conifer windbreaks to orchard floor weeds. Apparently, psylla eat dandelions. “Nobody knew that,” said David Horton, a fellow ARS entomologist working with Cooper.

—Psylla also sometimes leave the orchard early in the fall but return in November. At least, Cooper found evidence of that once. More testing will determine if that was a fluke wind gust or a pattern.

—Psylla don’t always eat where they live. Researchers sometimes found no DNA in psylla guts of the plants from which they collect the bugs. For example, they beat a lot of psylla out of weeping nootka cypress, a landscape conifer outside Cooper’s office also known as Alaska cedar, but found no nootka markers in their guts. At least, not so far.

—They expected to find some psylla with only pear gut contents, figuring some of the insects simply never left the orchards in the winter. That was not true. All the psyllids sampled had evidence of eating other things.

—Certain methods for gut content analysis work better than others. Cooper’s team started using a gel-based method that included cloning and sequencing PCR-amplified strands of plant DNA in psylla. That proved the concept, and it would have worked for small sample sizes and if psylla have a limited diet, but it is too time-consuming and expensive for use on psylla that have fed upon many different types of plants. Cooper has since switched to newer high-throughput sequencing, which provides thousands of data points at once, sending his samples to the Washington State University laboratories in Pullman for analysis.

—Certain traps work better than others. Sticky traps often left the bugs too torn up to yield clean DNA samples, so Cooper’s team may turn to traps that capture bugs straight into a preservative.

An overwintering pear psylla on a beat tray found in a tree located near the USDA ARS laboratories in Wapato, Washington, on January 8, 2018. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Status

Cooper and his collaborators have finished what he calls the “methods” portion of the project, funded by a two-year $29,000 grant from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. He plans to continue the work using the more sophisticated DNA screening but look for funding from other sources.

Other collaborators include Beers; Dalila Rendon, an Oregon State University postdoctoral associate; and Richard Hilton, an OSU entomologist. They have been sending Cooper samples of psylla from orchards near Wenatchee, Washington; Hood River, Oregon; and Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Each of those areas offer different shelter plants and winter feeding options for the psylla.

The psylla’s dietary variety throws a few wrenches into their research. “It makes things a little more complicated than what we intended when we first started out,” Cooper said.

But they expect the more efficient analysis to show some patterns over time, hopefully robbing some of the psylla’s mystery.

“This insect never surprises me,” Horton said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment