Skin and flesh color in cherries, as in apples, vary widely from dark red to almost colorless due to differences in anthocyanin pigmentation. Breeding blushed yellow cherries, like Rainier, is complicated by the fact that the yellow skin color trait comes from recessive genes, says Dr. Cheryl Hampson, cherry breeder for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, in British Columbia. Hence, you can cross two dark cherries, and some of the offspring may be blush cherries.

In theory, if both parents have only dominant red genes, all the offspring are likely be red cherries. If one parent has dominant red genes and the other has a recessive yellow gene, then all the offspring should still be red.

However, if both parents carry recessive yellow genes, then 25 percent of the offspring should be yellow. With a cross of a yellow cherry and a red one with the recessive yellow gene, half the progeny should be yellow. A cross of two yellow cherries should result in yellow offspring.

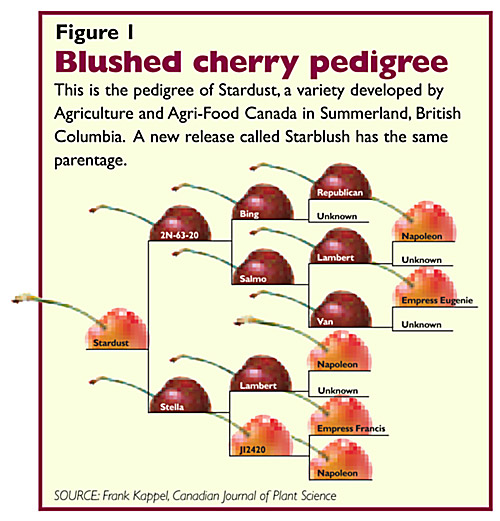

Figure 1 shows the pedigree of Stardust, a blushed cherry variety developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Summerland, British Columbia, that was released four years ago. A newer variety called Starblush came from the same parentage.

Figure 1 shows the pedigree of Stardust, a blushed cherry variety developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Summerland, British Columbia, that was released four years ago. A newer variety called Starblush came from the same parentage.

Dr. Amy Iezzoni, cherry breeder at Michigan State University, said since the yellow pigment gene is recessive, one would think yellow cherries would be rare, but many of the major sweet cherry varieties today—including Bing, Lapins, and Regina—are carriers of the yellow gene. Iezzoni and her collaborators have discovered that the main gene involved in cherry skin and flesh color is an anthocyanin transcription factor on chromosome 3—the same one that is responsible for skin color in apples. A genetic marker is being developed that would allow breeders to determine if a variety or seedling has the yellow gene.

Crosses

Iezzoni works as a consultant with Washington State University’s sweet cherry breeding program in Prosser. When she started making crosses at WSU in 2004, developing new blush varieties was one of her goals. Knowing which varieties carry the yellow-skin gene and which did not, enabled her to make crosses with the greatest likelihood of success. For example, about 25 percent of seedlings from a cross of Bing and Regina should be yellow-skinned, and half the offspring from a cross of Regina and Rainier should be yellow.

WSU cherry breeder Dr. Nnadozie Oraguzie said seedlings from crosses that Iezzoni made in 2004–2006 are fruiting and are being evaluated. He has 8,000 phase-one seedlings in the breeding program plots at Prosser, and 15 second-phase selections. Of those 15, three are blush cherries. After another three or four years of evaluation, outstanding selections will go on to phase-three.

Oraguzie said one of the objectives identified by the breeding program’s Industry Advisory Committee was to develop blush varieties that mature earlier or later than the industry standard, Rainier.

Oraguzie and his colleagues are using genetic markers to select for self-fertility and fruit size, both to determine desirable parents for crosses and to select the best progeny when they are in the juvenile phase in the greenhouse, so that the least promising ones can be eliminated early on.

Markers are also being developed for time of maturity, bloom date, firmness, sweetness, and acidity, as well as the one for skin and flesh color, Oraguzie said.

Leave A Comment