The race to develop an autonomous apple harvester got shaken up last summer when the leading company, Abundant Robotics, shut down and filed for bankruptcy after it was unable to raise additional funds from venture capital or growers.

Co-founder and engineer Curt Salisbury recently told the tree fruit industry that despite technological progress, Abundant wasn’t able to commercialize fast enough, at a low enough cost, to keep investors intrigued.

“The problem ended up being much harder than we thought at the outset,” he said during a talk at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Annual Meeting in December.

But despite Abundant’s experience, other ag tech companies focused on apple harvesters remain undeterred, with at least four planning to have technologies in different phases of development in Washington orchards this fall. They all say the demand and business case for robotic harvesters remains strong, as growers face ever-increasing labor costs and shortages.

“It doesn’t mean the case for robotic harvesters has diminished in any way,” said Ittai Marom, the chief operations officer for Tevel Aerobotics Technologies, an Israel-based company developing a harvest approach that uses flying robots to navigate the apple canopy. “One of the things we’ve realized is that developing technologies like this for agriculture is not a sprint, it’s a marathon.”

Lessons from failure

Salisbury, now a scientist with Amazon, acknowledged in his talk the subject is not his favorite, “but hopefully it will be of use,” he said.

He outlined Abundant’s intended business model: to be a service provider performing harvest for growers at a low price to drive rapid adoption of the technology. The venture capitalists who backed the company wanted to see Abundant charge $20 per bin and reap a 50-percent margin, so the company would have to pick for a cost of $10 per bin.

“That’s pretty aggressive, but that’s what we signed up for,” Salisbury said.

However, capital costs of the machine were too high and the pick rate, at 66 minutes per bin, was just too slow. Investors wanted to see them picking thousands of bins, but they just had one machine. While they solved the fruit quality issues and delivered impressive packouts, Salisbury said both the pace and the machine’s reliability in the field were problems they ran out of time and money to solve.

Salisbury thanked the industry for its support, including funding through the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission and individual companies that sent a message to investors that this problem was worth solving. He also thanked the “visionary growers that would let us come out and make mistakes over and over in those orchards.”

“I didn’t like to talk about this when I was with Abundant, but competition is good, and getting more shots on goal is great,” he said. Ongoing industry support, through the commission or through offering prize money, will continue to show the venture capital community that robotic harvest is still worth the investment.

Advanced.Farm, a Sacramento, California-based ag tech startup that developed strawberry harvesting technology, purchased Abundant’s harvester at the urging of its investors, said Peter Ferguson, the head of business development.

“I think there’s a lot we can learn from it,” he said, “But we won’t be resurrecting it.”

Instead, they’re examining how to apply what they’ve learned from development of their TX Robotic Strawberry Harvester and meeting with growers who worked with Abundant to learn what worked and what didn’t. For example, they’ve learned that a robotic harvester needs to integrate with the apple bin system, he said.

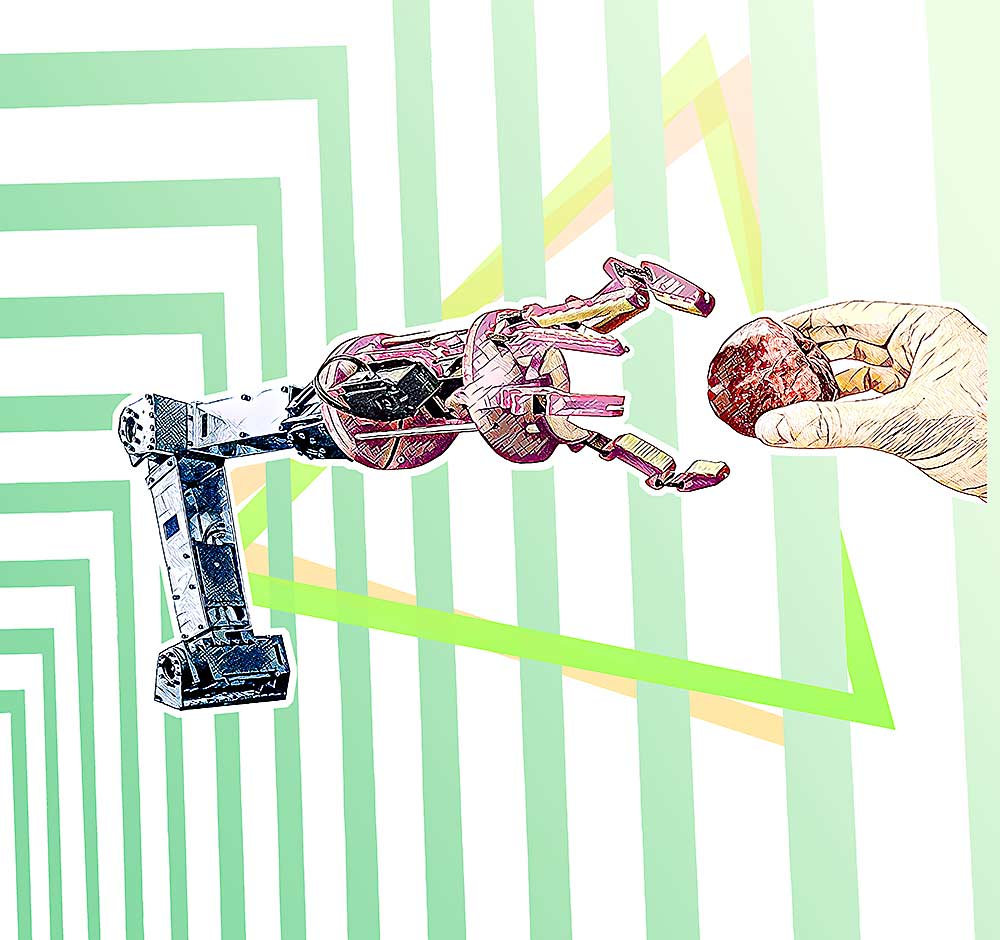

“The way you would grip and pick an apple is different from how you would grip and pick a strawberry,” he said, but the vision systems, robotic arms, grippers and autonomous drive systems they have developed should all be applicable. “We’ve dealt with the same problems in strawberries and feel prepared to do it again in apples.”

For Avi Kahani, the CEO of Fresh Fruit Robotics, the lessons from Abundant’s bankruptcy are more about the business case than the technology. Growers pay a lot more than $20 per bin for harvest with today’s labor costs, but it’s the bins per hour that’s key to making machine harvest possible, he said.

“The charge should be competitive and improve the growers’ profitability. The real value is that growers will soon learn it’s much easier to manage the machines than the people,” Kahani said in an email interview. “The market is suffering and the machine will give benefits to the grower with all-day availability, ability to perform multiple operations, and provide orchard management insights that will deliver more profitability.”

He expects to set standard, per-bin prices for harvest as a service, depending on variety; the machine should be able to pick multiple bins per hour. His company is also looking to leverage the data the machine collects on crop load and eventually incorporate mechanized pruning and blossom thinning by swapping out the tools on the ends of the robotic arms. Robotic pruning should help to create tree architecture suited to mechanical harvest, and finding multiple uses for the technology should help spread out the capital cost of the machines.

Optimizing canopy structure is less of a concern for Tevel Aerobotics, because its flying robots — stabilizing quadcopters with a vision system and a small picking arm — can approach the canopy from multiple angles, Marom said. “If you look at Abundant, it probably had three degrees of freedom, left/right, up/down, and in/out. We are able to get six degrees, which allows us to get almost every fruit in the canopy,” he said. “It’s more agile, more flexible, and we believe it’s more cost-effective.”

They aim to have one robot pick at the equivalent pace of one worker, Marom said. They aren’t there yet, because their 2021 trial in an Italian orchard focused on fruit quality — ensuring that the robots can pick and deposit fruit in the bins without bruising.

“That was the highest priority of the pilot we did, and we passed the bar in terms of quality,” he said. “Now, our interest and focus goes back to speed.”

The company also seeks potential partners with bin-handling platforms to mount the flying robots. Tevel plans to do its first harvest in Washington this year, Marom said.

Another company, Australia-based Ripe Robotics, also hopes to do limited trials with its vacuum harvester in Washington this season, and Advanced.Farm will start trials this year as well, with support from the research commission.

There are advantages to not being the first tech company to tackle these challenges, said Kyle Cobb, president and co-founder of Advanced.Farm. The door is already open.

“Growers have had many years to think about automation and how to change the orchard to accommodate it,” he said. “To have that more-evolved thinking has really benefited us.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment