Climate change won’t make a fruit grower’s job any easier.

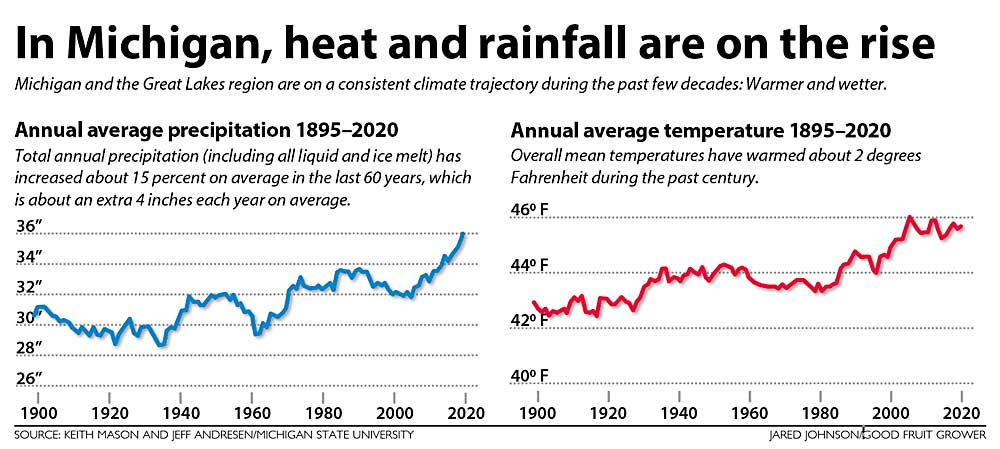

Since 1895, the average mean temperature in Michigan has risen about 2 degrees Fahrenheit, and average annual rainfall has risen about 4 inches. The biggest jumps in temperature and rainfall have occurred since 1980, said Keith Mason, outreach coordinator for Michigan State University’s Enviroweather program.

For many fruit crops, warmer and wetter weather, especially in winter and spring, is leading to earlier bloom, greater risk of frost damage and more pest and disease problems. Tart cherries in Northwest Michigan, for example, reached side green stage in the middle of May 120 years ago; these days, they reach it in late April. The past few decades also have seen a decrease in the amount of ice on the Great Lakes during winter, leading to faster and less predictable spring warm-ups, he said.

Mason was the first speaker of “Managing Fruit Production in a Changing Climate,” an educational session held during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO in December. He spoke on behalf of Michigan state climatologist and MSU professor Jeff Andresen, who was unable to attend the session. Following Mason, a panel of MSU specialists discussed short- and long-term strategies for managing climate-resilient fruit.

Speakers mentioned a few possible upsides of climate change for fruit production — higher temperatures lengthening the growing season, for example, or delaying pest emergence — but overall, they were pessimistic about the effects of a warming climate on Michigan fruit. Precipitation is becoming more extreme, with episodic droughts followed by intense rain events; insect generations are increasing per season; and diseases traditionally limited to warmer southern regions are creeping north.

In other words: The job of the fruit grower is going to be harder and more complicated, with much less room for error. They can spray more, of course, but pesticides are expensive and can lead to pest resistance, potentially removing a useful tool from the toolbox. Panelists recommended selective spraying and mixing modes of action, but with erratic weather leading to shorter and less predictable spray windows, that won’t be easy.

MSU plant pathologist George Sundin said that increasing fungicide resistance will make the physical removal of diseased tissue from the orchard an essential task.

“Those kinds of labor-intensive techniques will become more important as we lose the tools to manage diseases,” he said.

Sundin said new pathogens are already migrating north into Michigan. Bitter rot moved into the state in the past several years. Warmer temperatures during bloom have led to an increase in fire blight, too (see “Fire blight surges”). And the popular apple cultivars grown today tend to be more susceptible to diseases than were older varieties, he said.

MSU small fruit and hop pathologist Timothy Miles said Michigan blueberries and grapes will be hit with fungal and bacterial pathogens they haven’t experienced before. Xylella fastidiosa, which causes Pierce’s disease, for example, is a huge problem in California grapes, and another strain causes bacterial leaf scorch in Georgia blueberries but hasn’t been a problem in Michigan. That could change as Michigan warms.

Sundin said climate change is exacerbating fungal diseases. Higher temperatures speed fungal growth, and longer and heavier rain events decrease spray windows and wash pesticides off fruit.

“We have to be very proactive the whole season with disease control,” he said. “Any slip-up, any miss, will be tough to come back from.”

MSU postharvest physiologist Randy Beaudry said the same thing about the postharvest process. Temperature controls, storage timing, 1-MCP (1-methylcyclopropene) applications — storage operators must pay attention to every detail in order to preserve fruit quality.

MSU horticulturist Todd Einhorn shared a few strategies the industry can use to adapt to the changing climate. Breeding rootstocks and scions for adaptable traits — delayed bloom, for example — will be crucial in the long term. In the shorter term, protective measures such as frost fans and netting will grow in importance. So will more accurate predictive temperature and precipitation models.

Einhorn said growers must pick the best sites for their new plantings, and those new plantings must include supplemental irrigation. Michigan growers traditionally have not relied on supplemental irrigation, but increasing periods of drought and rain will require more consistent watering.

“We should be irrigating frequently,” Einhorn said. “There’s no reason to suffer episodic drought events when water is available.”

MSU tree fruit IPM specialist Julianna Wilson said climate-resilient practices include crop diversification. She also said non-crop habitats on fruit farms can be important reservoirs for beneficial insects like parasitoids. Maintaining these habitats to increase beneficial insect populations should help suppress pest populations as part of an integrated pest management program.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment