Start with a clear and answerable question. Randomize treatment plots. Keep data collection consistent. Those are among the bits of advice Jon Clements has for growers launching their own on-farm trials.

The University of Massachusetts Amherst Extension educator encourages growers to try out new products or techniques before investing full-scale, but he reminds them to respect some basic principles of experimental design to get the most for their efforts. He calls those trials on-farm research and suggests that growers approach even simple experiments like any full-time researcher would.

To explain how, Clements gave a primer on the scientific process at February’s annual meeting of the International Fruit Tree Association in Rochester, New York, sharing his list of 10 steps for successful on-farm research.

“These are the steps you really need to be thinking about if you’re going to go through and do your own on-farm research,” he said.

1. Pick a good question. Answering that question is the overall goal, so make it specific and clear. As an example: “Can I reduce my chemical rate and still get good disease control?”

2. Form a hypothesis. Make it testable, measurable and contain both independent and dependent variables. “I am going to spray a half-rate of fungicide and expect disease control to be 100 percent, which will not differ from using a full rate.” The fungicide rate is the independent variable, the amount of disease control is dependent.

3. Decide what data to collect. Examples are yield, fruit size or disease incidence.

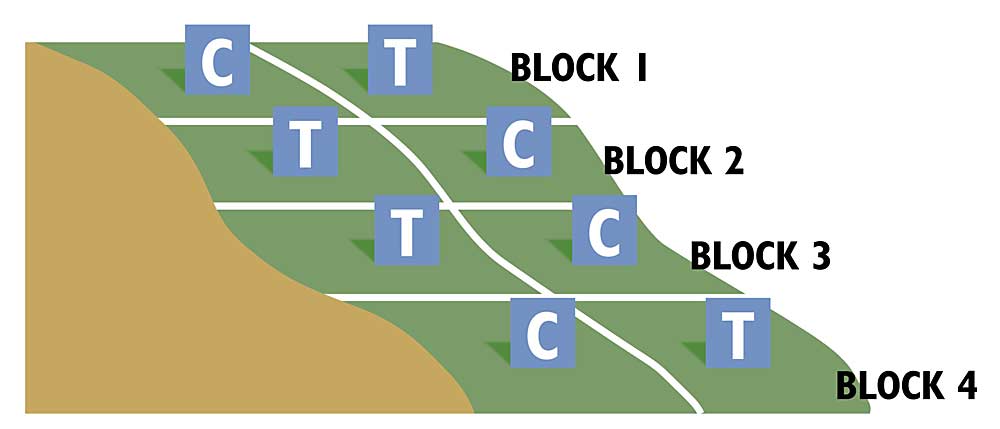

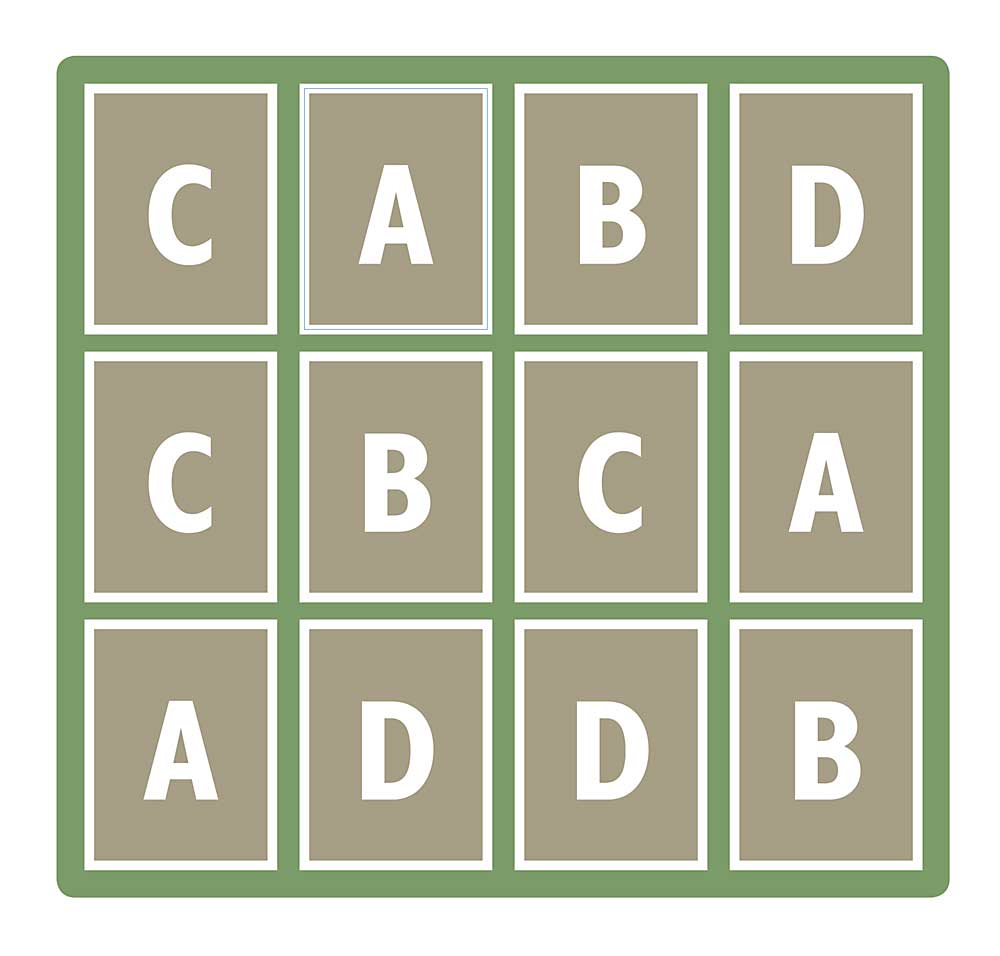

4. Design the experiment. This step takes some work. Clements recommends keeping the experiment simple with only two or three treatments. Repeat all treatments over different trees, plots or rows. Randomize to reduce the effect of other factors. For example, trying one spray on plots at the top of a hill and another spray on plots below allows elevation, moisture and soil differences to cloud results. Plan to repeat trials a second year to rule out changes in weather.

5. Choose a location and flag the plots. Pick accessible fields with uniform soil and topography with treatment plots big enough for data collection, separated with buffers around and between them. Remember to include control plots. Map the project.

6. Implement the research. Follow a written protocol about where, how and when to apply treatments. Other than changing treatments, manage all plots the same. Communicate with employees and field representatives to prevent inadvertent sabotage.

7. Make observations and keep records. This is different than data collection. Notice anecdotes such as, “bloom density seems to be much lower in this/these plots.” Keep a notebook.

8. Collect data. Prepare data collection sheets ahead of time. Organize and label collection bags for samples. Keep samples from different treatments and plots separate.

9. Analyze data. Crunch numbers, find averages and try to make sense of the data, most likely with a computer. Seek help if necessary. Clements admits he’s sometimes found himself stumped looking at data and does not mind helping growers analyze their spreadsheets. “But please talk to me before you start the experiment,” he said.

10. Draw conclusions. Go back to the hypothesis and either confirm or debunk it. Get a second opinion.

For more detail, Clements recommends reading on-farm research guides published by university extension programs, such as “On-farm Vineyard Trials: A Grower’s Guide,” by Washington State University, or the federally financed Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education grant and education program (northeastsare.org/Grants/Get-a-Grant/Farmer-Grant).

Generally speaking, Clements recommends growers be realistic and practical, managing expectations of time, costs, labor and equipment to avoid getting mired in an all-consuming project.

“I’m as guilty of that sometimes as other people,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment