A study examining different rates of nitrogen application for Anjou pears resulted in some very boring data, according to the lead researcher.

“This is the least exciting but also sexiest data set I have ever seen,” said Ashley Thompson, Oregon State University Extension educator, as she presented her findings to Hood River pear growers in February.

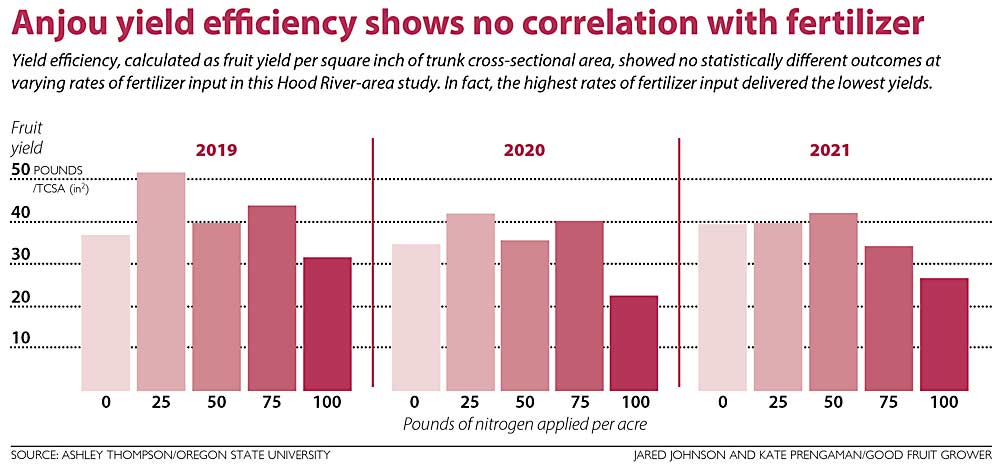

That’s because the lack of significant difference between her treatments shows that in Hood River’s rich soils, Anjou pear yield does not depend — at least in the short term — on regular fertilizer inputs.

“There’s no statistical difference in the pounds of fruit per tree,” she said, across three years of data collection.

That’s good news for growers who watched fertilizer prices go through the roof the past few years, she added.

In Anjou blocks, growers are already fighting vigor, so cutting back on nitrogen just makes sense, said Tim Pitz, a horticulturist with Mount Adams Fruit. He favors low rates, around 20 pounds per acre.

Thompson’s findings do help to show that in Hood River’s rich soils, many growers don’t have to worry about yield implications from temporarily backing off nitrogen, said agronomist Bruce Decker, but he cautioned against extrapolating the findings from the one Anjou block where Thompson collected data to other blocks across the region.

“I don’t think it’s that simple,” said Decker, a senior agronomist with Wilbur-Ellis. “My comment over the years has been: ‘The tree will tell you how much nitrogen it needs.’”

Thompson agreed, saying that growers need to actually look at their trees and conduct soil tests and leaf nutrient analyses. She sees the findings as a short-term reassurance for growers facing high input prices, not necessarily a long-term prescription.

The study, funded by the Columbia Gorge Fruit Growers, stemmed from Thompson’s surprise upon moving to the region and finding OSU’s published application recommendations, which felt outdated and high.

“We don’t typically see trees with a nitrogen deficiency. It’s often applied in excess,” promoting vigorous growth that leads to high pruning bills, along with fire blight and psylla problems, Thompson said.

“You shouldn’t be cutting 5- or 6-foot suckers out of your Anjous,” she said. Reducing inputs could save growers money and have horticultural benefits in some cases. “Our 100-pounds-per-acre rate is really underperforming compared to other rates.”

She found a relatively young block of Anjou, planted on OHF 97, and a grower willing to let her experiment. She applied nitrogen at rates of zero, 25 pounds, 50 pounds, 75 pounds and 100 pounds per acre and assessed tree growth, leaf nutrition, pear yield and pear quality.

Over three years, while the trees grew and yields increased, she saw no statistical variation in yield or fruit quality.

Grower Parker Sherrell, who bought the orchard after Thompson started the study, said he is pulling back on nitrogen across the block, and the data confirms he is heading in the right direction.

“It’s helpful to see the data on throttling back nitrogen. It’s easy to see that more is not better,” he said. He’s planning to cut back to 20 pounds or even take a year off nitrogen entirely, as the 11-year-old trees are now very strong.

The findings clearly reflect the region’s soil, which is high in organic matter and holds on to nitrogen far more than sandy soils, Thompson said. Trees need nitrogen for growth and fruit production, and studies have shown that every ton of pears harvested removes 1.65 pounds of nitrogen, while pruning off a year’s worth of structural wood growth removes 13 pounds.

The success with zero inputs raises some questions about how the block was managed before the trial, Decker said. Sometimes growers will throw more and more nitrogen on an underperforming block, when insufficient irrigation, high pH or rodent damage may pose the real problem, leading to a soil excess that can support the trees for years.

That could certainly be the case at the trial block, Sherrell agreed. He had to tackle a gopher problem, prune aggressively and adjust the irrigation to get the block in better shape, he said. In a nearby older block, soil samples showed high nitrogen, but the leaf levels were not high.

“It makes no sense to throw more nitrogen at it if the trees aren’t using it efficiently,” Sherrell said.

In such cases of soil excess, Decker has recommended applying zero nitrogen and said it can take five years or longer, in some cases, to get a block back in balance.

“You don’t have to be afraid to go to zero if you are dealing with a high-vigor situation,” Decker said. “In a well-balanced, high-organic soil with a larger tree system, there is enough nitrogen stored up that you are not going to fall off a cliff.”

Today, most of the region’s growers apply far less than the 150 pounds per acre that OSU recommended in the 1990s, Thompson said.

Decker said he works with a lot of growers applying 40 pounds of nitrogen annually, and it “looks really good.” Other places are using 60.

“Our grower base is pretty dialed-in. Most people have figured out that they can get by with a lot less nitrogen than the old-timers used to talk about,” he said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment