When Oregon State University entomologist Vaughn Walton and his graduate students demonstrated that a fruity-smelling gum could reliably distract female spotted wing drosophila away from blueberries enough to help growers reduce their sprays, they celebrated.

But it turns out, demonstrating the viability of their discovery was only the start of an arduous journey toward commercialization and pesticide registration. Walton formed a company to license the intellectual property from OSU and began to explore how to deliver the product.

It sounds simple, but it’s not, he said. Challenges abound.

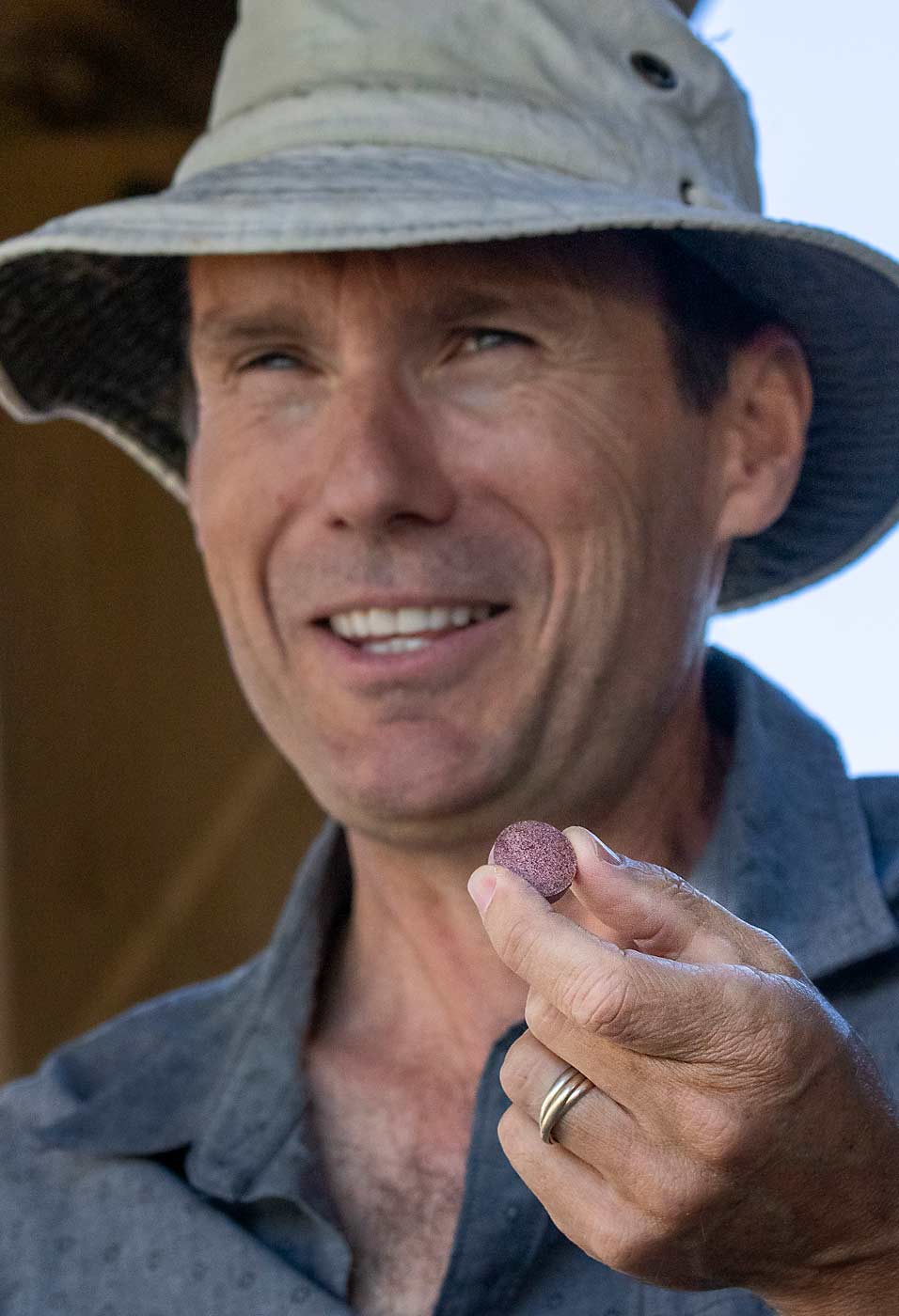

First, the gum was transformed into easy-to-manufacture tablets, which then need to be held in a small cup that can hook onto the drip line. The gum requires regular moisture to remain active.

“This is not entomology anymore, it’s 3D printing and tablet making,” Walton said of the company he founded, TerrAmor.

The combination of food-grade materials produces a fruity aroma even more attractive to SWD than blueberries, so the females lay their eggs in the gum instead of the fruit. There, the eggs desiccate and die. However, the materials also attract rodents and deer, which can eat the biodegradable cardboard containers that Walton’s team initially designed. Now, they’ve turned to recyclable plastic, designed to allow SWD maximum access and enough water retention to stay moist but not hold standing water.

Meanwhile, Decoy, the trade name of the gum, has been in the registration process with the Environmental Protection Agency for three years. As a biopesticide that uses only natural, nontoxic ingredients, Walton thought registration would be relatively straightforward, but using novel ingredients — such as cherry — can bog down the process.

Frustrated, he decided to pursue a different avenue to commercialization and reformulated the product so that it could be considered a “minimum risk insecticide,” which is not regulated at the federal level, only registered state by state.

This state-by-state approach should get Decoy on the market in 2022 in the West Coast states, he said, and when the EPA eventually approves the biopesticide registration, it will be more widely available. It’s commercially used in a few other countries as well, Walton said.

The initial work into the gum’s performance to reduce SWD damage was funded by the Oregon Blueberry Commission, the Oregon Sweet Cherry Commission, the North American Raspberry and Blackberry Association and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But the commercialization efforts are now self-sustaining, Walton said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment