Berry and cherry growers across the Western U.S. have largely been successful in preventing spotted wing drosophila damage to their crops, but many are using weekly insecticide covers to do so. To tiptoe back toward integrated pest management, researchers are testing a wide variety of alternative controls and approaches.

Researchers are conducting trials on a handful of novel deterrents, repellents and attract-and-kill products, as well as continuing research into cultural controls, narrowing in on fruit susceptibility and understanding spotted wing drosophila phenology and behavior in Western climates. This year, the effort expands to include studying the potential control offered by a pair of parasitic wasps that target SWD (see “Green light for biocontrol”).

And they are doing it within a collaborative umbrella of scientists from everywhere SWD-susceptible fruit crops are grown, all of whom have been working together for nearly a decade to understand the pest, with funding support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative.

“If a technology is developed in one place, it’s evaluated in multiple regions and multiple crops,” said University of Georgia entomologist Ash Sial, who leads the project team of scientists from 10 universities and the USDA. “The ultimate goal of this project — and this is the third SCRI project; the first two focused on developing a set of short-term management control programs — is to develop more sustainable approaches to control SWD in the long term.”

Sial said the current project has several areas of focus: monitoring for insecticide resistance; developing trapping protocols; testing new insecticide modes of action; beginning to study biocontrols; and evaluating behavioral controls, such as attract and kill or deterrent products.

To get a preview of the behavioral control approaches under review, Good Fruit Grower visited Oregon State University entomologist Vaughn Walton last summer. Walton’s research led to the development of one behavioral control he’s commercializing and sharing with other researchers for evaluation, while his lab group tests many other emerging approaches at OSU’s research farm in Corvallis.

Blueberries

Netting cages dot Walton’s blueberry field, each containing five bushes. He calls them “inclusion netting” instead of exclusion netting, within which they release a standard number of SWD per cage to create consistent levels of pest pressure for trials.

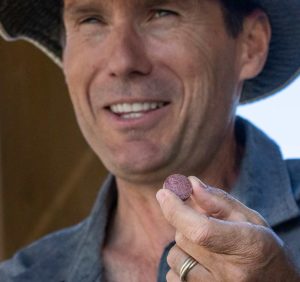

He used this approach for initial testing of Decoy, the behavioral control his lab developed several years ago. It’s a gum, made of food-grade materials, that’s even more attractive to female oviposition than blueberries, hence the name. But when females lay eggs in the gum, the eggs dry out and die. Last year, it was deployed on hundreds of acres of blueberries and caneberries in different regions under an experimental use permit (see “From entomology to engineering”).

“You put 50 of these out per acre and it lasts 21 days,” he said. “Here in Oregon, we’ve found growers can really cut their traditional pesticide sprays around 70 percent.”

In other regions with higher pressure, growers are using it in combination with existing spray programs to reduce SWD damage 30 to 50 percent, Walton said.

The Decoy gum comes in the form of a small tablet, which sits in a container that hangs over the drip line, because the gum must remain moist to attract SWD. That may be limiting for growers without irrigation, Walton said.

Since he formed a company to commercialize the technology, Walton is no longer studying Decoy in his role as an OSU entomologist, but he’s providing it to other scientists to study in their crops and climates, such as part of the new Spotted Wing Drosophila Areawide Project led by USDA entomologist Jana Lee.

“Decoy is one we’d like to put out in bigger numbers,” Lee said.

At OSU’s farm, Walton is now evaluating a host of other alternative controls, including a repellent sachet developed at Cornell University and a repellent cover spray developed at the University of Notre Dame.

Another under review, a promising spray additive from a German company, known as combi-protec, encourages more SWD feeding, allowing growers to reduce the rate of Entrust (spinosad) they apply but retain efficacy. So far, it’s looking good, Walton said.

Another approach: a protective film developed at OSU that increases the waxy cuticle and, therefore, firmness of the berries by about 10 percent. That may not sound like much, but “that’s enough to deliver significant reductions in egg laying in blueberry,” Walton said.

Cherries

While Decoy is promising in blueberries, in cherries it’s a little more complicated.

“It’s a matter of scale,” said Chris Adams, an OSU entomologist based in Hood River. On a large cherry tree, there’s more fruit to compete with than in a blueberry system.

Washington State University entomologist Betsy Beers also struggled to deploy the deterrent last year. The regular wetting required is a challenge in Eastern Washington’s arid climate and in the cherry systems there, which tend to have microsprinklers or drip lines too far below the canopy.

Walton said he has seen positive results with Decoy in cherries in more humid Western Oregon, and it will take time to adapt it to other systems.

Beers said she has her eye on other emerging products, such as those Walton is testing, but most of her trials take place in commercial orchards, where regulations limit what can be done with products that are not yet registered, she said.

“The manufacturer isn’t motivated to register until they have efficacy data, and we can’t get enough efficacy data until they’ve registered,” she said.

WSU entomologists are also looking at how the postharvest control programs in development for the leafhoppers that transmit X disease might also impact SWD.

“If the control for one insect helps control the other one, that’s great,” said WSU entomologist Tobin Northfield. The work is in its early days, but the use of Extenday and Surround as leafhopper deterrents also seems to reduce SWD populations in the orchard after harvest.

“One of the problems is that the SWD still tend to build up after harvest, with fruit on trees and on the ground harboring SWD and potentially contributing to the next year of damage,” Northfield said.

In The Dalles, Oregon, area, Adams has noticed that SWD seem to hang around cherry orchards long after harvest, unlike in Michigan and many other Eastern U.S. climates where the surrounding landscape offers more alternative hosts.

That may be good news.

“If they leave your orchard, there’s nothing you can do to control them,” he said. “But if they are on your property, maybe we can go after that winter population and knock them down before spring.”

He just received funding from the Oregon Sweet Cherry Commission and Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission to study this seasonality, but if the findings hold, it opens up more options for using alternative controls, he said.

“It gives us an opportunity to attack them off-season when an attractive bait is more attractive,” he said.

Maybe the bait could work better in the off-season, when it has less fruit to compete with, for example. Or perhaps erythritol, a sugar substitute that the USDA’s Jana Lee has shown is fatal to SWD who consume it, could make a bigger impact in the winter when the insects have fewer resources.

Adams is also assessing how much an already registered coating — Parka, developed at OSU to prevent cherry cracking — can reduce SWD damage, and he’s trying to understand when, in terms of ripening, sweet cherries become susceptible.

“If that yielded a week or two when we didn’t need to spray, and then Parka bought us a week and then we could knock them back in the winter. … If we can move the needle just a little bit with all of these approaches, that’s the way to get back to IPM,” he said.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment