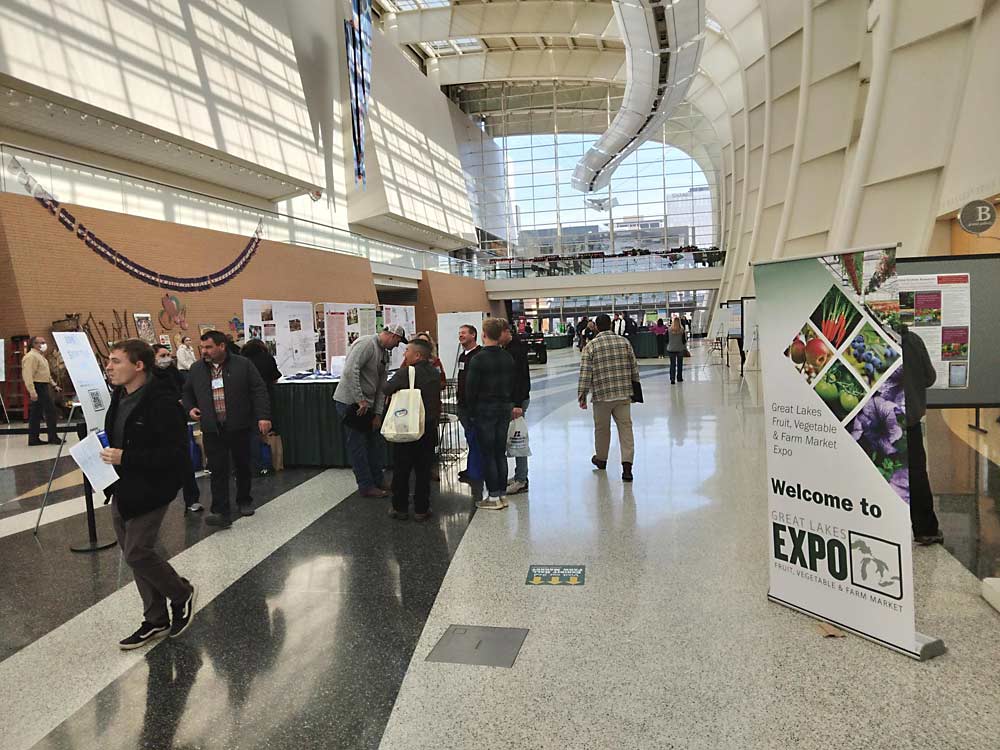

The Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO is back in-person this year, after being held in a virtual format last year.

Day 1 of the EXPO, held in DeVos Place Convention Center in Grand Rapids, Michigan, included an educational session on fruit production technologies. The first speaker was Keith Mason, program and outreach coordinator for Michigan State University’s Enviroweather program. Enviroweather recently revamped its website and is expanding its weather station network.

Enviroweather provides weather monitoring for growers in Michigan and Wisconsin, performing an important service for fruit producers. The program has 105 weather stations spread through both states. Many are clustered in big fruit production regions like the Fruit Ridge, Northwest and Southwest Michigan and Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula.

Growers who don’t farm in these regions, or growers who live in unique microclimates, might need more location-specific data collection, Mason said.

To solve this problem, Enviroweather is expanding its network by adding personal weather stations that can be maintained by individual growers, providing data that can be shared by the entire network. The program is studying five different models right now, and so far all are performing well. They’re easy to assemble, and most come preprogrammed from the manufacturer. The models range in cost from $2,500 to $3,500, he said.

They plan to test-run the models in 2022 and design the necessary software and databases. They hope to on-board the first user-owned stations in 2023, Mason said.

The next speaker was Kirk Babcock, a contractor with Rantizo Solutions, an ag drone spraying company.

Babcock said drones have been used for spraying pesticides overseas, but it’s a fairly new practice in the United States, he said.

Drones complement existing spray technology and don’t replace ground-based spray tools. As a relatively new method, the potential seems almost limitless. Operators keep finding new uses for them in different crops, he said.

Advantages of drone spraying include application flexibility (good for spot spraying, which is useful for specialty crops), no chemical overuse and less pesticide exposure.

Challenges include battery size (they can only fly for so long), spray tank size and swiftly advancing technology costs. Spray-drone operators need certifications to fly the drones and apply the pesticides. They also need insurance, Babcock said.

Drone spraying technology was only recently approved in the United States, and Babcock doesn’t have a lot of experience spraying specialty crops. But based on other studies, drones can spray 5 to 10 acres of vineyard per hour. Costs can total $150 per hour, Babcock said.

Mark Ledebuhr of Application Insight talked about the secondary impacts of implementing new technology on the farm. Technology is a tool, but it’s not always a savior, he said.

Autonomous technology can do a lot of good on the farm, saving on labor and operations while increasing precision. Robots can work 24 hours a day. They don’t skip rows. They don’t have to take the kids to soccer practice. They reduce risks, too. When spraying, for example, robots can monitor environmental conditions and stop if they fall out of parameter. It’s harder for people to do that, Ledebuhr said.

But when you add new technology to the farm, you’re not just adding one piece of equipment. You’re adding an ecosystem. You need internet connectivity; you need to manage and store your data streams. That means you need a dedicated IT person, or to hire someone to do that for you, he said.

Refilling robot sprayers can get complicated. Machines need to be charged and maintained. Another potential problem: Do technology companies understand the demands and reliability requirements of your operation?

People in the tech industry are very smart, but most don’t understand agriculture. Does the company understand the conditions its machines will operate in? Will the machines meet “industrial severe duty” standards, Ledebuhr asked.

Other risks include new insurance and underwriting requirements, and the fact that robotic systems could be exposed to hackers, he said.

The Great Lakes EXPO continues with sessions Dec. 8 and 9.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment