The challenge of managing powdery mildew and botrytis bunch rot could be getting harder for Michigan grape growers due to the development of fungicide resistance.

Timothy Miles, an extension specialist who manages Michigan State University’s Small Fruit Pathology Laboratory, discussed his lab’s efforts to study fungicide resistance in both diseases during the 2019 Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market EXPO in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in December.

Miles said both pathogens display abundant resistance to commonly used fungicides in Michigan. Resistance occurs when a pathogen population changes from being sensitive to a fungicide to being insensitive to it. At first, only a small fraction of the pathogen population is resistant. But over time and repeated exposure to that fungicide, the resistance trait will grow throughout the population via continued selection pressure.

“If that fungicide keeps getting applied, the whole population shifts,” Miles said.

Unfortunately, new fungicides are a rarity for grape growers, which limits their management options.

“There’s a lot we use over and over again,” Miles said. He’s concerned that current fungicides might not work as well as they did when they were first labeled.

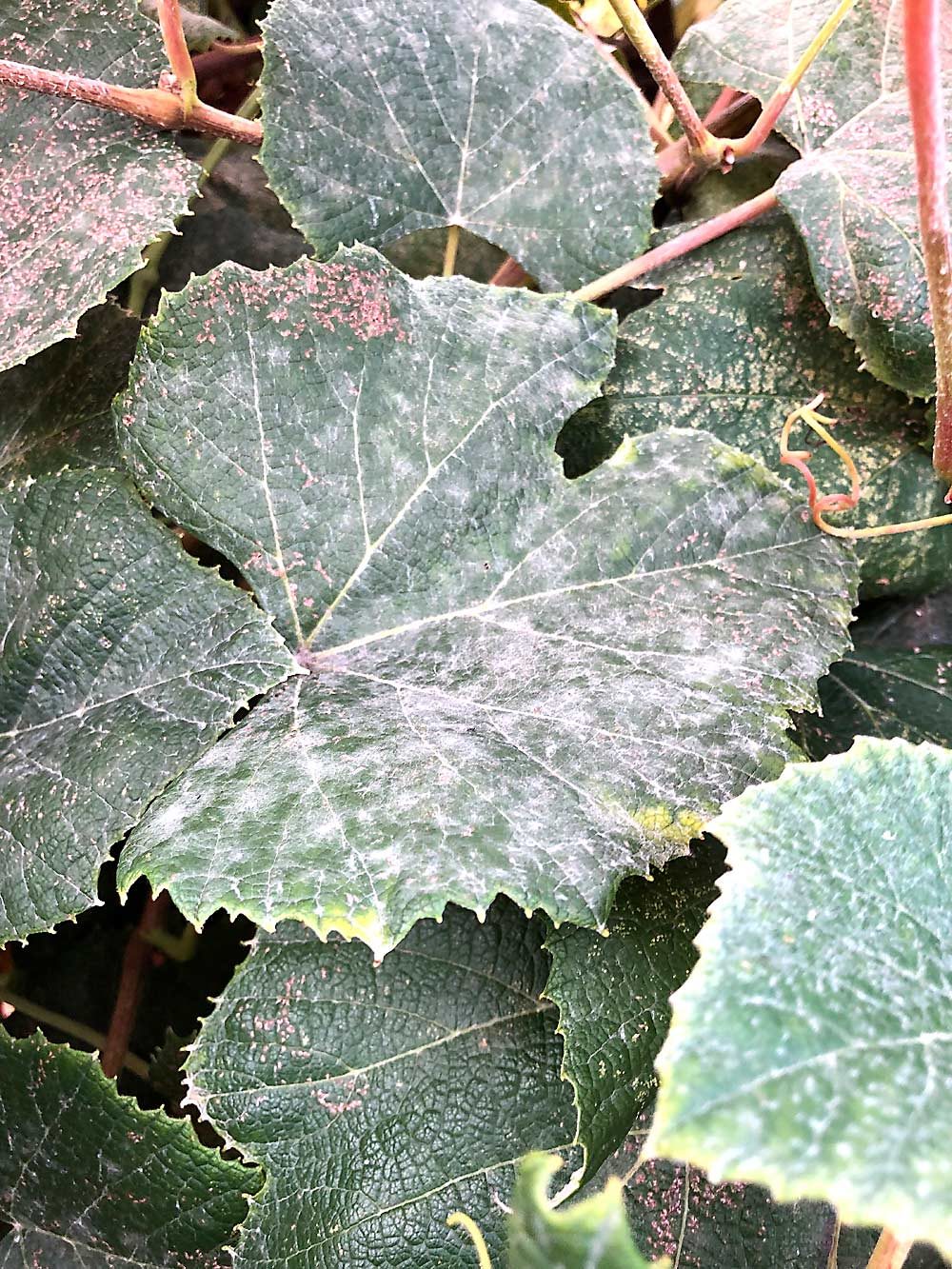

Powdery mildew, caused by the fungal pathogen Erysiphe necator, is probably the most devastating disease of grapes across the globe and requires intense management, he said. It occurs wherever grapes are grown. Miles is collaborating with researchers across the country on a U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant-funded project to assess fungicide resistance to powdery mildew and mitigate the impacts.

Effective management requires the use of numerous prophylactic fungicide applications. But due to economic and logistical constraints, growers only use a few fungicide classes to control the disease, which can result in the rapid development of fungicide resistance in the pathogen population. Miles said FRAC 11/quinone outside inhibitor fungicides are showing resistance.

From a research perspective, powdery mildew is a difficult disease to work with. It doesn’t grow easily in a laboratory, so studies require outdoor field research and newer molecular tools, Miles said.

Botrytis cinerea is a pre- and postharvest pathogen that causes bunch rot in grapes. The disease can cause grape harvest loss of up to 100 percent. Several fungicides are used for control of the pathogen, including anilinopyrimidines, quinone outside inhibitors, hydroxyanilides, dicarboximides, phenylpyrroles and succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors, according to Miles.

However, the pathogen has developed resistance to single or multiple fungicides at several locations in Michigan, and resistance appears to be increasing throughout the state’s vineyards. The highest levels of resistance were found with FRAC 11/quinone outside inhibitor fungicides and FRAC 7/succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides, Miles said.

Growers who suspect powdery mildew resistance can submit samples to Miles (milesti2@msu.edu) and Nancy Sharma (sharm115@msu.edu) during the 2020 season, as part of the USDA project. Currently, there is no available service to detect fungicide resistance in botrytis, but options are being explored, Miles said.

With limited chemical tools available to manage fungicide resistance, Miles emphasized the importance of good cultural practices for grape growers. He made some general recommendations:

—Open up the canopy and dry it out.

—Rotate fungicide usage. (Include newer biological products and older contact products when possible.)

—Don’t apply half-rates.

—Target sprays around bloom.

—Use dormant sprays to keep inoculum low.

—Practice better sprayer coverage. (Apply throughout the entire canopy at the right droplet sizes.) •

—by Matt Milkovich

Related:

—Good to Know: Why some seasons are worse for powdery mildew

Leave A Comment