Signs of cherry powdery mildew developing resistance to several commonly used fungicides prompted researchers to ask growers to pause use of those at-risk products.

Washington State University plant pathologists Gary Grove and Prashant Swamy are sounding an alarm about resistance to two fungicide categories they found throughout Washington and Oregon. They suggest growers find other ways to manage powdery mildew for two years, to save those products’ efficacy for the long haul.

“There is both good news and bad news,” Grove told growers in January in his virtual presentation at the annual Cherry Institute. “But I think if we do things right that the good news will prevail.”

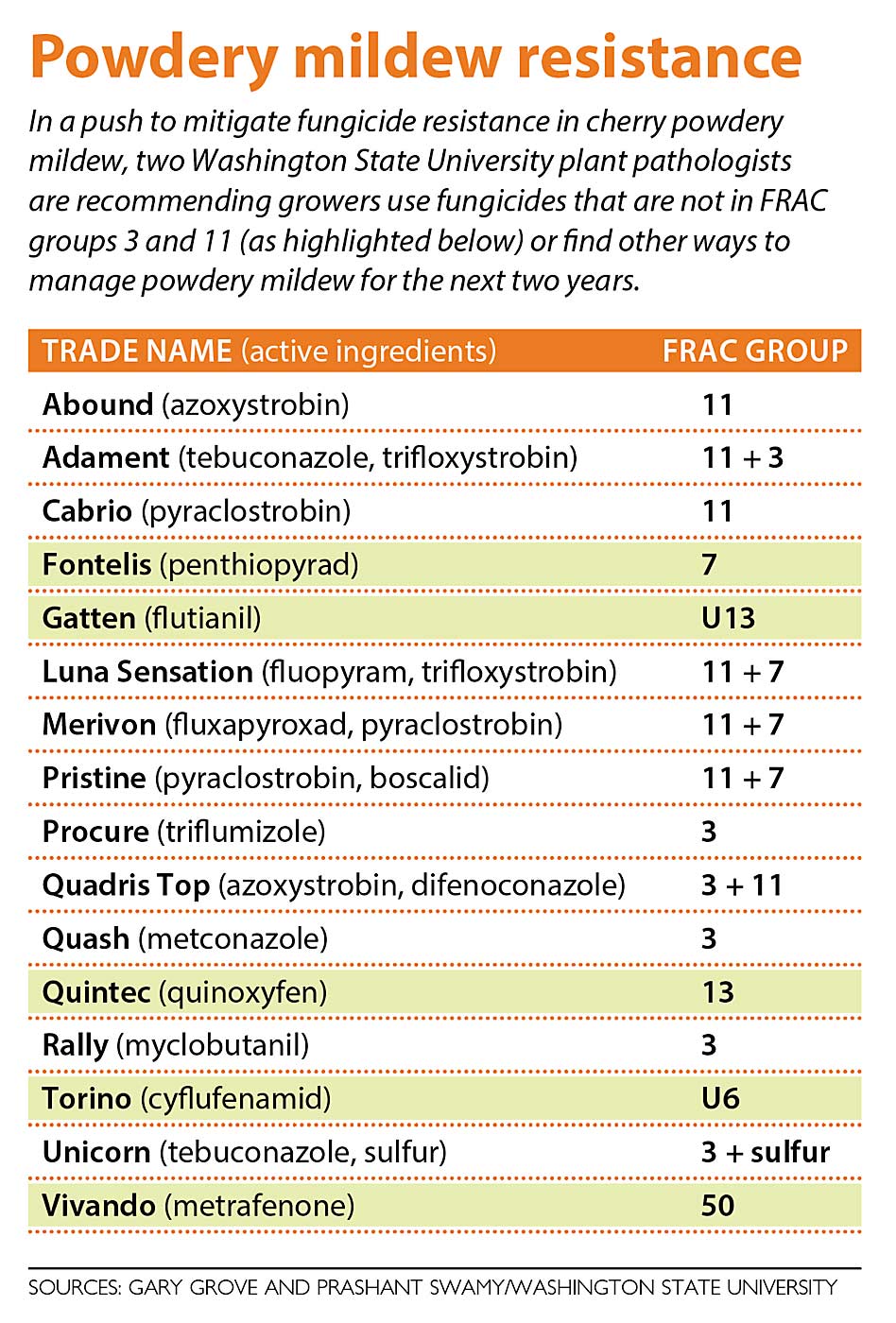

Over the course of a three-year project, Grove and Swamy detected evidence of cherry powdery mildew resistance to chemicals in FRAC groups 3 and 11 in all production areas of the Northwest. Also as part of the project, they studied fungal genes related to resistance and tested resistance among nursery trees.

The Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, Oregon Sweet Cherry Commission, Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration, WSU Agricultural Research Center and the Northwest Nursery Improvement Institute provided funding for the work.

Powdery mildew in cherries develops mid- and late season as a white, powdery covering on the surfaces of fruit, rendering it unmarketable. WSU recommends a season-long program of pruning, suckering and irrigation management, as well as spraying, to keep the pathogen in check.

The Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, FRAC, groups fungicides by their modes of action. Alternating between groups or tank mixing helps avoid, or at least mitigate, a pathogen’s natural ability to develop resistance to one particular mode of action over time.

In the commercial orchards Grove and Swamy sampled, 43 percent of the 192 isolates were resistant to quinone outside inhibitors, or FRAC Group 11 chemicals, which are also known as strobilurins. Meanwhile, 28 percent were resistant to demethylation inhibitors, DMI, FRAC Group 3 fungicides.

Shelving fungicides in groups 3 and 11 for the next two years will slow down and maybe walk back resistance by removing selection pressure, Grove said. Epidemiological studies have shown pathogens can revert back to their original states of “fitness,” leaving them susceptible to the fungicide once again.

“We’re actually doing things in reverse,” Grove said.

There’s no good time for resistance, but things could be worse, Swamy said during a follow-up interview. Pressure from powdery mildew should be relatively low this year because pressure was relatively low in 2019 and 2020. One bad year often bodes ill for the next because more inoculum is present.

But that doesn’t mean resistance is low, Swamy said. The little inoculum that is present in an orchard can still be resistant to fungicides.

Growers have noticed

Low powdery mildew pressure aside, growers have been complaining to WSU that fungicides that used to work well appeared to be losing efficacy, one of the telltale signs of resistance.

Cherry growers near Hood River, Oregon, have noticed, said Andy Rust, a crop consultant for Chamberlin Agriculture. They used to spray three or four times a season, rotating through the FRAC groups. Today, with more varieties and a longer season, they spray five to seven times. In contrast, the Hood River pear industry seems to need fewer sprays at longer intervals, even though they use the same materials and pears hang longer.

“It has something to do with the amount that we’re using in cherries that’s got the resistance spiraling out of control,” Rust said.

With that many sprays each season, avoiding two FRAC groups without repeating during the year — a resistance no-no — might be tough, Rust said. The most common cherry FRAC groups are 3, 7 and 11. The groups outside those consist of newer products that he and his growers are less familiar with.

Postharvest work could help, he said. Moving forward, he plans to suggest growers spray their trees with sulfur after they’ve picked, to reduce the inoculum load for overwintering. As long as it’s not too hot, sulfur applied after harvest poses less risk of burning leaves than before, while sulfur has low risk of resistance compared to synthetic fungicides.

Hector Torres of Zillah, Washington, also has tightened his fungicide application intervals over the years. The farm manager for Kahala Farms used to spray every two weeks. It’s more like between seven and 10 days now. And it doesn’t take long at the end of the season for mildew to spread.

“Once we stop spraying, a week later, 10 days later, almost immediately, you can see mildew all over the fruit,” he said.

Fungicide resistance is “an ongoing problem that we’ve dealt with forever,” said Denny Hayden, a grower in the Pasco, Washington, area.

In fact, he frequently takes chemicals out of his rotation. A few years ago it was Quintec, a FRAC Group 13 product. In 2021, he plans to rest Pristine, a premix of FRAC groups 7 and 11.

Other tools

Besides needing to spray more often, a catastrophic failure of control in a neighbor’s orchard could be an indicator of resistance in the area, Grove said in his presentation.

Swamy and Grove found evidence of resistance in all the production areas of Washington and Oregon, but they don’t know how widespread it is in each area because they could only sample so much. If growers are unsure, Grove suggests they assume they have resistance and act accordingly.

Growers still have plenty of options, such as fungicides in FRAC groups U6, 7, 13 and 50, plus sulfur and oils, which were the only tools available for decades and have low resistance risk.

“Sulfur’s cheap and it’s very effective if applied when conditions are right,” Grove said. Too hot, and it could burn foliage.

Oil works well to knock back existing populations, but it, too, can burn foliage at high temperatures. Even when applied sequentially at low temperatures, oil can accumulate on leaves then burn them when the weather warms up later. Also, oil can remove the marketable shine from cherries if applied between pit hardening and harvest, Grove said.

Other techniques for mitigating powdery mildew include pruning to allow canopy airflow and light penetration, suckering, calibrating sprayers to ensure adequate coverage and delaying irrigation in the spring.

For growers who absolutely must use groups 3 and 11, for example if they have already purchased fungicides and lack options, Grove suggests they use them only once during the season, tank mix with other groups or sulfur, ensure good coverage and use them at the highest label rates. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment