The Pacific Northwest pear industry lacked a phenology model for its No. 1 pest, pear psylla, until 2019, when Washington State University entomologist Vince Jones developed one as part of a $301,631 project funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission technology committee. Finally (!) a pear psylla phenology model was available.

However, development of pest management recommendations to accompany this model was not a part of the original project. Furthermore, effective pear psylla management must be selective to prevent killing off natural enemies with broad-spectrum insecticides. So, model-based recommendations would be complicated by the need to rely on selective insecticides and cultural strategies at precise timings; in other words, a fully integrated pest management (IPM) approach is critical.

To turn phenology predictions into a usable pear psylla management tool, our team, led by assistant professor Louis Nottingham, received $225,086 from the Northwest Fresh Pear and Processed Pear committees for a three-year project to develop IPM guidelines to accompany the pear psylla model. We leveraged this initial grant to gain further funding from the Washington State Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program ($249,926), the WSU BIOAg Grant Program ($39,993), and the Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration ($15,206).

Applying the pear psylla model for IPM

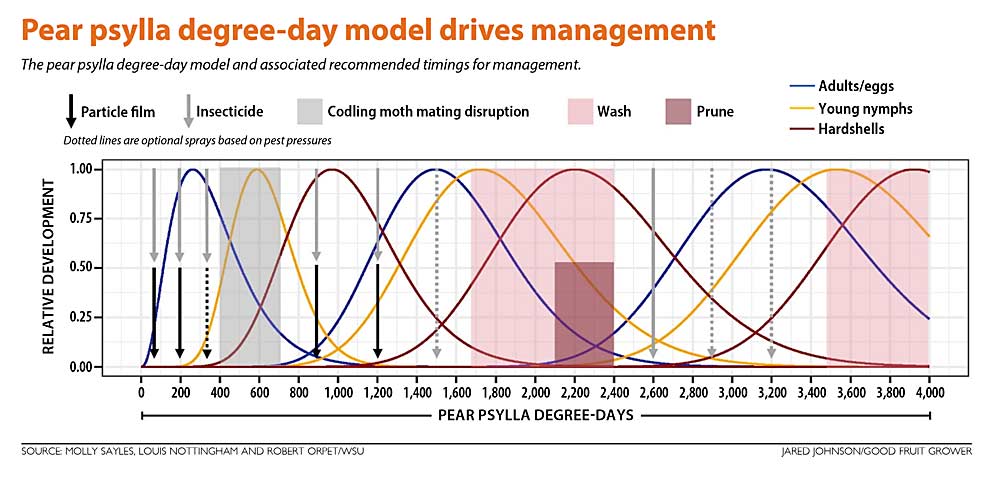

In the first year of this project, we created a pear psylla IPM program that links selective sprays (insect growth regulators and kaolin clay) and cultural strategies (tree washing and summer pruning) to degree-day timings. We also incorporated other phenology models (such as pear bloom and codling moth) to improve management of other pear pests.

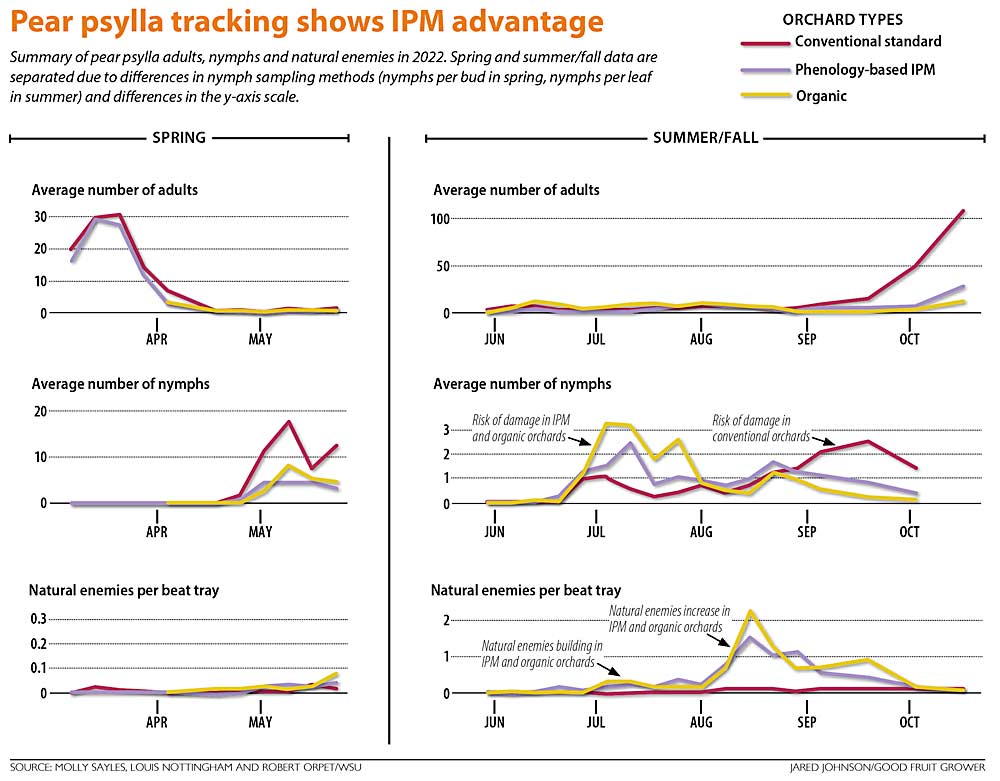

In 2021, we ran a pilot study in commercial pear orchards to get initial feedback from growers and refine the program. The IPM plots in the pilot study performed extremely well, so in 2022, our team partnered with 19 growers and consultants throughout the Wenatchee Valley to test the phenology-based IPM program again, but in more orchards. Eight orchards used the phenology-based IPM program, eight used conventional management and three used organic management.

We sampled the orchards every week for pests and natural enemies, then assessed fruit damage at the end of the season to determine the success of the phenology-based IPM program. We thought it was important to adequately challenge our program, so all but one pair of orchards involved large, old trees in areas of the Wenatchee Valley with high psylla pressure. Additionally, all orchards testing the phenology-based IPM program in 2022 had been under conventional (not IPM) management the previous year.

Psylla phenology program performance: It works!

In 2021 and 2022, the pear IPM program on average kept pear psylla densities similar to or lower than conventional orchards and led to major increases in natural enemies. In 2022, a high-pressure year for pear psylla, orchards following phenology-based IPM and organic programs had higher pear psylla nymphs during July, but these populations were eventually reduced by natural enemies before harvest. Meanwhile, conventional orchards saw pear psylla rapidly increase as harvest approached, resulting in risk of damage during sticky harvest times. Conventional orchards also saw tenfold increases in pear psylla adults going into the overwintering stage in the fall.

Fruit downgraded by honeydew was similar between phenology-based IPM and conventional programs, and no differences were seen among programs for other pests — including codling moth, mites and mealybugs. The phenology programs cost $143 less per acre than the conventional programs, on average. Therefore, if adopted across the 11,000 acres of pears in the Wenatchee Valley, this program has the potential to save the industry $1.6 million per year (a great potential return on the industry’s funding investment).

Our results demonstrate that this phenology-based IPM program is effective and economical even in the first year of adoption. Moreover, areawide adoption would result in a regional suppression of overwintering pear psylla due to conservation of natural enemies, leading to later-season biocontrol. This would greatly reduce the areawide populations of pear psylla, making management in future years easier and cheaper for all pear growers.

What’s next in 2023

We will continue testing the program in 2023, and we will continue to seek grants to carry on this work in 2024 and beyond. Because gaining areawide adoption of this program will further improve areawide psylla control, we encourage growers to use the phenology IPM guidelines, even if they are not working directly with our team. We also hope to track the adoption of this program, so please take the time to fill out a very short survey found at: bit.ly/wenatchee-pear-survey.

We appreciate all the grant funding that allowed this project to happen and the growers and fieldmen who have been willing to test the program.

—by Molly Sayles, Louis Nottingham and Robert Orpet

Molly Sayles is a doctoral student in entomology at Washington State University and can be reached at: molly.sayles@wsu.edu. Louis Nottingham is an assistant professor of entomology, now based at WSU-Mount Vernon, and can be reached at: louis.nottingham@wsu.edu. Robert Orpet is a research professor of entomology based at WSU’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee and can be reached at: robert.orpet@wsu.edu.

Learn more online: The pear psylla model and corresponding IPM guidelines are publicly accessible through the WSU Tree Fruit Extension website at: bit.ly/psylla-phenology-model and through the Decision Aid System. Weekly scouting data from 2022 orchards are also posted on the WSU Tree Fruit Extension website at: bit.ly/2022-pear-pest-scouting.

Leave A Comment