As the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission celebrates its 50th anniversary, we’re taking an opportunity to reflect on some of the significant research impacts that grower assessments have generated in three different areas: crop load management, integrated pest management and postharvest. Here, we talk about the significant gains made in chemical thinning research.

If you’ve interacted with very many research and extension folks, it is easy to get the impression that everyone thinks their particular field is the most important thing that anyone is working on anywhere, and those of us in the arena of crop load management of tree fruit are no exception.

Of course, topics like irrigation, insects, diseases, nutrition, etc. are all important, but there are very few decisions growers make regarding management of established orchards that have greater impact on their bottom lines than how to thin their crops.

With a relatively modest investment of grower dollars, chemical thinning research funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission (WTFRC) has helped drive significant advancements in how the industry manages its crop and sustains the economic viability of Washington apple orchards.

Growers have long understood that most apple trees have an inherent tendency toward biennial bearing: a cycle of producing high yields of small, low color, poor quality fruit in one year, followed by low yields of large fruit prone to various physiological disorders in the following year.

The most straightforward remedy to this unfortunate pattern is to reduce the crop load to a modest level every year, whether by chemical, manual or mechanical means. Thinning by hand is reliable and safe for the crop but has not been practical or affordable for many growers as a stand-alone practice, even decades before we had ever heard of expensive things like adverse effect wage rates or indexed minimum wages.

As such, researchers have been investigating chemical thinning options for apples for over a century, to help growers maintain good yields of quality fruit at reasonable production costs.

A quick history of chemical thinning

When the WTFRC was formed in 1969, most Washington apple growers relied on the chemical bloom thinner Elgetol (Sodium 4,6-dinitro-o-cresol) to manage their crops; in addition to turning tractors and orchard dogs yellow, Elgetol did a fine job of thinning apples. However, Elgetol was removed from the market in 1990 due to a lack of supporting data for re-registration by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In response, the WTFRC began funding chemical thinning research with Max Williams (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Wenatchee) and others to work on alternate chemistries — including carbaryl, which developed into the foundation of most postbloom chemical thinning programs around the country.

“The scheduled loss of Elgetol sent the industry frantically looking for alternatives,” recalls longtime WTFRC commissioner Jim Doornink. “The WTFRC realized that this issue was critical and began funding projects that might provide answers. Max turned industry into a bunch of ‘chemical thinning believers.’ Not only did we get larger, well-spaced fruit, we also saw greatly reduced hand thinning bills.”

Despite progress in the postbloom thinning arena, there were no clear candidates to replace Elgetol as a chemical bloom thinner. Two new products, Wilthin (sulfcarbamide) and Thinex (pelargonic acid), were introduced in the early 1990s but encountered difficulties due to inconsistent performance and tendencies to mark fruit.

The WTFRC continued to seek solutions to these problems by funding other researchers; one, Peter Sanderson, the first scientist hired by the commission, initiated studies to investigate potential chemical bloom thinners.

“The WTFRC board felt so strongly about chemical thinning that in addition to funding other projects around the country, we needed to commit to doing more work locally,” Doornink said. “This led to the assignment of WTFRC staff to work specifically on introducing new thinning products, a commitment that continues to this day.”

Other scientists funded at the time by the WTFRC include Kathleen Williams (Washington State University, Wenatchee) and the late, great Norm Looney (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Summerland, British Columbia), who helped establish the fertilizer ATS (ammonium thiosulfate) as a modestly efficacious thinner of apples. Unfortunately, no ATS product has ever been registered for use on tree fruit and could not be used in organic production systems.

The rediscovery of a forgotten tool

WTFRC efforts scaled up considerably in the late 1990s when Jim McFerson assumed leadership of the chemical thinning research program and hired me as his technician.

We learned a lot from our predecessors and contemporaries in the field, but encountered our greatest stroke of luck in 1999 when we met organic tree fruit icon Harold Ostenson, who enthusiastically shared his experiences of thinning apples, cherries and stone fruit with various combinations of fish oils, fish emulsions and lime sulfur, an old product that was reported to reduce fruit set in the 1930s.

These “new” programs immediately showed promise in WTFRC trials, and, over the next decade, we were able to work out the details of effective thinning strategies using lime sulfur with and without various spray oils, all the while developing a robust library of trial results that ultimately proved the superiority of those programs versus alternatives like ATS, Wilthin and Thinex.

After the loss of Elgetol, Washington apple growers had an increasingly difficult time managing their crops solely relying on the use of postbloom thinners like carbaryl and NAA (naphthalene acetic acid). Many well-managed orchards slipped into crippling biennial bearing cycles, and growers needed new tools to help wrestle their blocks back into balance.

In 2004, Rex Lime Sulfur from Orcal Inc. received a Section 24C (or Special Local Needs) registration in Washington, allowing the first legal use of an effective apple bloom thinner since the 1980s.

It also marked the first time that a material approved by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) was labeled for thinning of apples, providing an effective tool to address a challenge that had previously been one of the primary barriers to sustainable organic production, and helping ignite the robust expansion of the organic apple industry in Washington that continues to this day.

Over the past two decades, the WTFRC has funded research projects related to chemical thinning and crop load management with scientists around the country. These projects have helped improve our understanding of the physiology and mechanisms behind various thinning chemistries, developed predictive models to inform chemical thinning decisions, enhanced our understanding of thinner effects on floral initiation and gene expression, and helped identify new chemistries with potential as thinning agents.

These projects were often subsidized by grants from private industry, state and federal funding agencies, but fundamentally represented an investment of roughly $350,000 of Washington apple growers’ hard-earned money.

During that same time period, the WTFRC internal program has conducted roughly $1 million of apple crop load management-related projects led by Jim McFerson and/or me; roughly three-quarters of the costs of these projects have been leveraged from private industry, primarily by registrants of various chemical thinners and plant growth regulators who have hired us to provide independent third-party evaluation of their products.

The net cost to industry for our internal crop load management research program has been approximately $250,000, or $10,000 per year. When combined with funding for external scientists, the overall investment by Washington apple growers in WTFRC-funded chemical thinning research totals roughly $600,000.

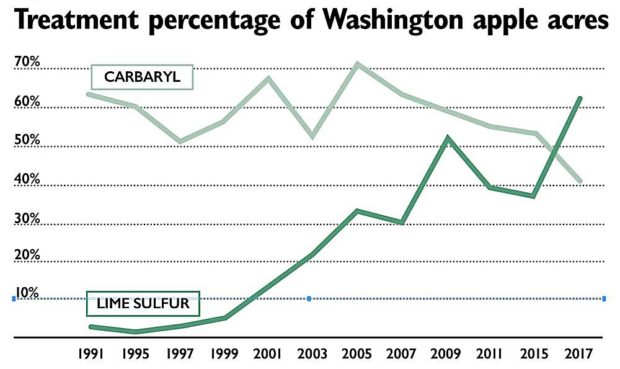

While it is difficult to quantify the economic return on that investment to industry, it is clear that chemical thinning practices for most Washington growers have evolved over the last 20 years: The percentage of apple acres treated with lime sulfur has increased roughly 1,000 percent, while the corresponding percentage of acres treated with carbaryl is down by a third (see Figure 1).

The latter figure is surely influenced by the reduced use of carbaryl as an insecticide and the increase in organic acreage, but also suggests that some conventional apple growers are finding enough success with their chemical bloom thinning programs that they are less reliant on applying carbaryl as a postbloom thinner.

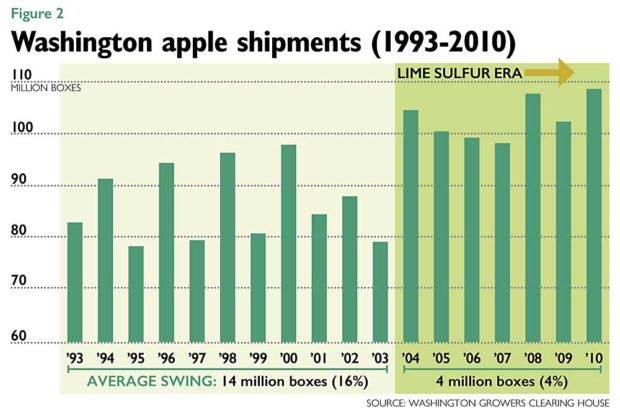

Further, a review of historic statewide apple shipments reveals a distinct biennial bearing pattern in the decade prior to the registration of lime sulfur as a bloom thinner in 2004 (see Figure 2); after industry began thinning broadly with lime sulfur, year-to-year statewide production evened out considerably, helping deliver a better product to the consumer and higher returns to the grower.

Former statewide coordinator of WSU’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources (CSNAR) and organic tree fruit guru David Granatstein notes that the evolution of lime sulfur — from an obscure curiosity used in isolated organic apple blocks to the primary chemical thinner for the entire Washington industry — offers a few other lessons as well.

“First, it illustrates the potential benefit of investigating and trying to validate a practice or idea that has evolved on the farm, outside normal research channels, where the tendency can be to discount it,” he said. “Second, it supports the value of organic systems in providing new ideas that all growers can use.”

Current and future directions

It isn’t often that a new product comes along that has potential as a chemical thinner, but we are quite optimistic that metamitron, an herbicide used in sugar beets, can develop into a cornerstone of successful crop load management programs.

It has performed impressively as a postbloom thinner in WTFRC trials for several years, as well as in other studies around the country. Metamitron is already being used extensively in Europe, New Zealand, Chile, South Africa and other countries around the world under the trade name Brevis; we hope to have this product registered in the U.S. within the next few years, particularly as consumer market pressures on the use of broad-spectrum pesticides like carbaryl continue to build.

The other exciting advances in chemical thinning research are in the development and application of various models to improve the consistency and predictability of crop load management.

The pollen tube growth model, developed by colleagues at Virginia Tech almost exclusively with WTFRC funding, was used in nearly 1,600 Washington apple blocks last year to improve the timing of bloom thinning sprays.

The WTFRC also continues to fund a project led by Vince Jones (WSU-Wenatchee) and Gloria deGrandi-Hoffmann (USDA-Tucson) seeking to model the foraging behavior of honeybees in apple and cherry under variable weather conditions, with an eye toward providing some prediction of fruit set.

Of course, Washington growers will be pleased to know that there is other important research being done around the country, for which they are not footing the bill, and we look forward to learning more from good work being done by a number of scientists.

We are hopeful this will include a large national Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI) project led by Terence Robinson (Cornell University) on precision thinning, which will seek to integrate the best available predictive models with cutting-edge crop load management techniques to improve the predictability and consistency of fruit set.

Applied research is, by nature, an optimistic enterprise, predicated on the belief that there must be a better way to get things done — there is no guaranteed return on investment, and in fact, most research efforts never return a penny to their stakeholders.

It is truly gratifying to those of us in the agricultural scientific community to contribute to work that “moves the needle” for our industry, and we hope you would agree that the WTFRC’s investment in chemical thinning research has indeed been money well spent. As always, we welcome your feedback and suggestions for how we might better serve our industry. •

—by Tory Schmidt

Tory Schmidt is a horticultural research associate for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. This column is part of a series examining the research advances made to benefit growers and the tree fruit industry during that time.

Leave A Comment