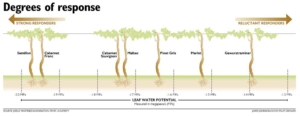

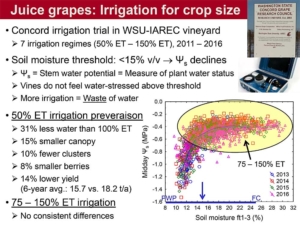

Markus Keller has long studied how grapevines respond to water stress, as the Washington wine industry uses deficit irrigation to bring about the complex flavors and quality of wine.

But extreme heat waves throw growers a curveball, and Keller, a Washington State University viticulturist, wants to understand how grapes respond to both heat and water stress.

Shifting climate patterns are increasing the frequency and duration of extreme heat waves in the summer, when grapes are ripening. “We don’t really know if that is a good thing or a bad thing,” Keller said.

Hot temperatures in the summer, typically defined as 95 degrees or higher, can cause sunburn and affect the acid development of fruit, he said.

Keller’s laboratory has three ongoing projects that explore heat effects and how to manage for them.

One, Keller and his colleagues call “The Double Whammy” experiment, because the vineyard management trial aims to study how grapes ripen under both water and heat stress together. The three-year study is funded by the Washington State Wine Commission’s Grape and Wine Research Program; 2021 is Year 2.

Through leaf removal and training, managing vines to expose fruit to morning sunshine is a common industry practice in Washington, especially for red varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, to develop pigments and tannins. However, Keller and graduate student Evan Fritzke are learning that too much sunshine — and the temperatures that come with it — has a negative effect on white wine grapes.

“Maybe we’ve been overdoing it,” Keller said.

To explore this in the trials, Fritzke removes leaves and trains shoots up when grapes are about pea-sized in July, exposing clusters to morning sunshine — just like normal industry practice. But come August, at veraison, he drops those shoots to shade the ripening fruit in both Chardonnay and Riesling grapes. Personnel changes prompted by the coronavirus and wildfire smoke have either delayed or skewed some results, but so far, they have found that post-veraison shading maintains higher levels of malic acid, a desired taste attribute in white wines, especially Riesling.

Researchers continue to analyze the sample berries at the university’s Wine Science Center in Richland.

Keller also is working on a project with Amit Dhingra, a plant genomics professor at WSU, to search for the expression of genes that control ripening in Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling. It’s funded by a Specialty Crop Block Grant. They want to determine whether heat stress causes similar effects as water stress or if they combine for something unique, Keller said.

So far, Keller’s team has discovered that water stress controls canopy growth and other plant responses, so producers can use it as a tool with which they manage fruit qualities. However, the water stress itself does nothing directly to the fruit. Heat stress, on the other hand, drives fruit characteristics.

This debunks some popular wine production beliefs, Keller said.

One important bit of advice he offered for growers: Avoid water stress during heat waves.

Dhingra continues to work on the genetic analysis of the berries from the project.

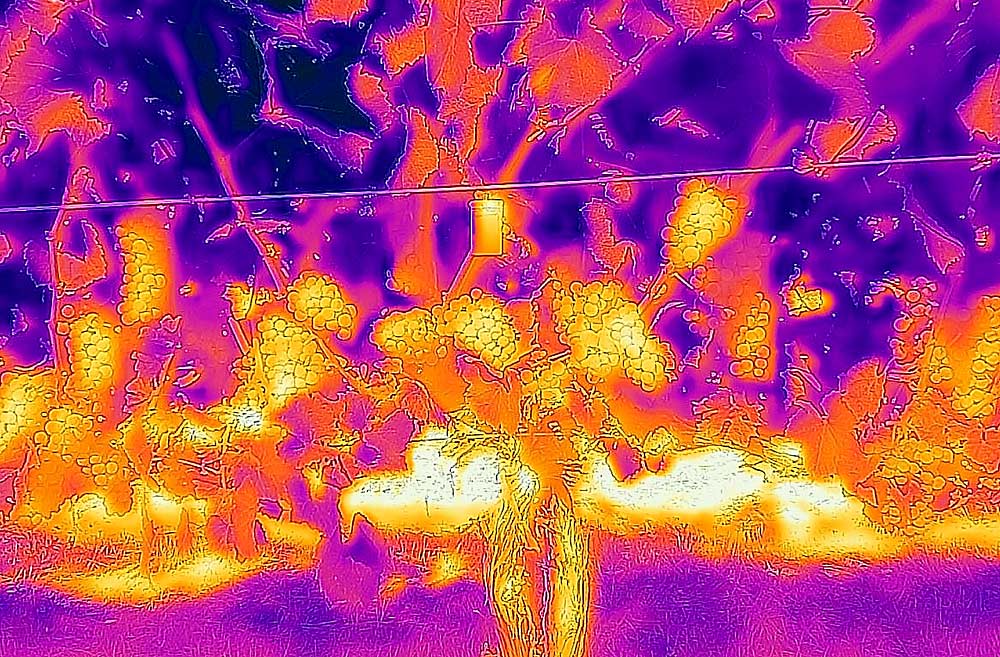

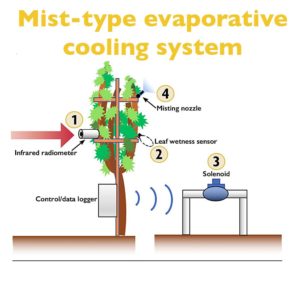

A third project, Keller’s evaporative cooling trials, funded by the Northwest Center for Small Fruits Research, has shown that it’s possible to use a misting system to cool grapes without watering the soil, which would throw deficit irrigation programs out of whack. Postdoctoral scientist Ben-Min Chang developed the misting system, and, so far, they have determined they can do it without causing diseases. Now they are measuring the effects of evaporative cooling on wine quality, Keller said. Winemakers have speculated it will cause negative effects on flavors.

Climate change is real, and the industry needs to react, said Wade Wolfe, co-owner and winemaker at Thurston Wolfe Winery in Prosser. But he said that Keller’s research would help the wine industry with or without climate change.

“We’re trying to understand how we interact with climate change while we still maintain or even improve the quality of the fruit,” said Wolfe, who also sits on the wine commission’s research advisory committee.

But the benefits go beyond that, he argued. All wine-producing regions need research that aims to understand regional environmental constraints and how to adapt growing and winemaking practices to produce the best quality possible.

“We’re always trying to see what we can do … to optimize the quality of the wines we’re making,” Wolfe said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment