Jon Clements was studying a grower’s MAIA1 (the apple marketed as EverCrisp) planting in western Massachusetts in October when he noticed some of the trees were partially defoliated, and there were strange-looking black and brown spots on some of the leaves.

The grower told Clements, an extension educator with the University of Massachusetts Amherst, that in the past he had observed similar blotches in this block — planted three or four years ago on Geneva 41 rootstock. The MAIA1 trees were already picked by the time Clements saw them and had not been treated with fungicide in over a month. The condition affected the leaves but not the fruit, so it wasn’t affecting the grower’s bottom line.

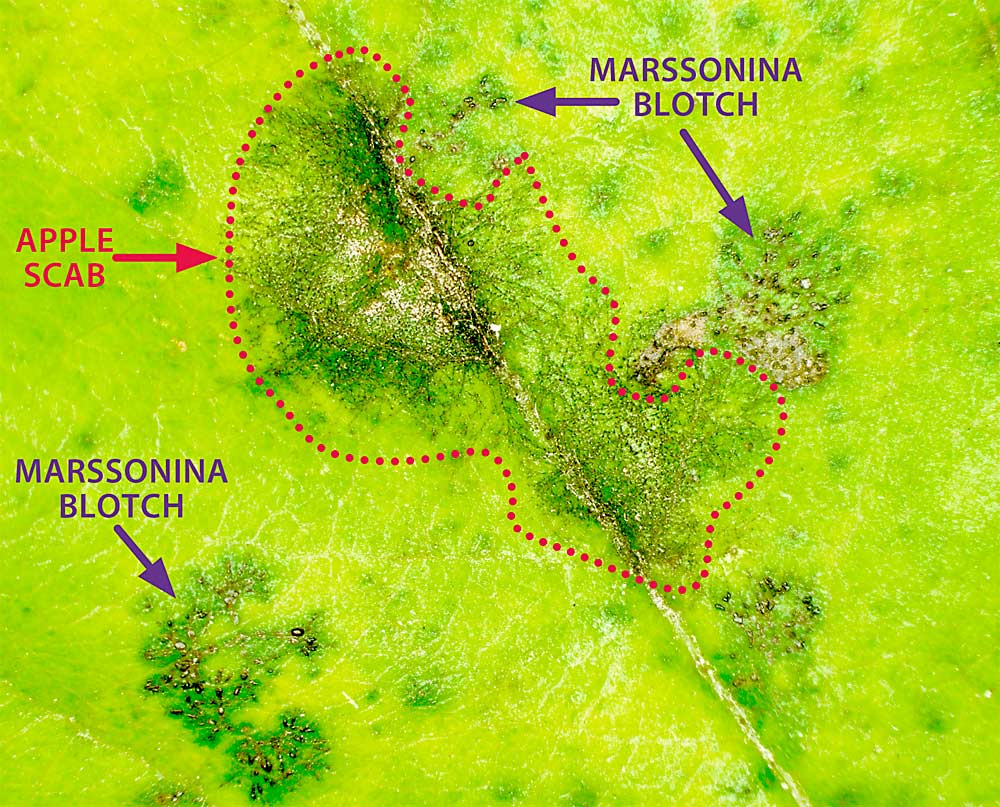

Clements suspected the chlorosis and defoliation were caused by marssonina blotch, a symptom of the fungal pathogen Marssonina coronaria. He’d already observed the disease at the UMass research orchard in Belchertown and at a nearby organic orchard. After consulting with Kari Peter, a tree fruit pathologist at Penn State University who has been studying marssonina for the past few years, he felt more certain of his diagnosis.

Marssonina coronaria poses a new problem for apple growers in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions — and probably beyond. Researchers have yet to reach a consensus on certain basic facts, such as how long the disease has been in North America, exactly how and when it infects trees and the susceptibility of different varieties.

There are a few facts they do agree on: Marssonina blotch has become more of a problem in the past few years, and it appears to be here to stay. Like its sister species, apple scab, marssonina thrives in warm, wet conditions, but unlike scab, it’s a season-long problem. And although marssonina is not yet listed on any fungicide label, typical scab management programs can keep it at bay — as long as growers stick with their sprays, especially after it rains. If they ease off their applications just before harvest, marssonina blotch can show up in their trees a few weeks later.

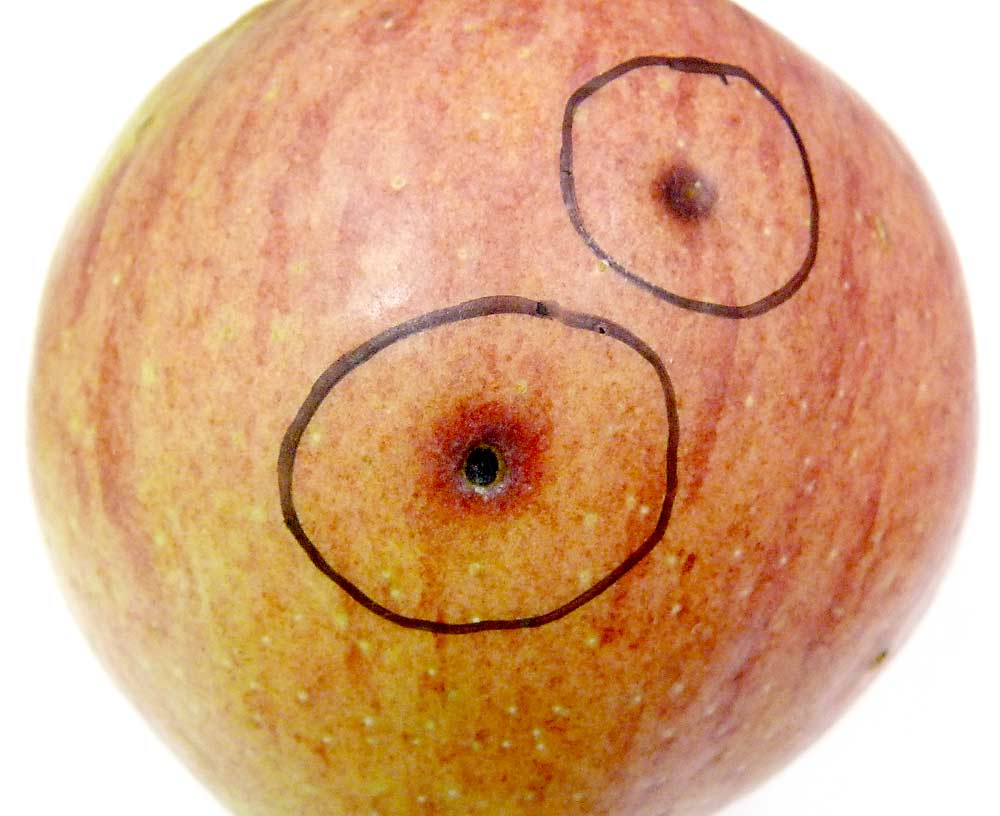

Because its symptoms primarily appear on leaves, not fruit, the disease does not yet pose a significant economic threat to apple growers. But increasingly wet summers could lead to a buildup of inoculum, which will have long-term effects on tree health and, sooner or later, that pressure will probably lead to fruit infestation. Once fruit becomes a target, Marssonina coronaria could pose a serious threat.

“It hasn’t been a real headache on fruit just yet, but there’s a significant pathogen buildup going on,” Peter said. “The level of concern is not as heightened as I’d prefer.”

New arrival?

How long has Marssonina coronaria been in North America? Has it been here for a century or more, hiding out in woods, suppressed by conventional fungicides or mistaken for scab? Did it just show up in the past few years? Researchers don’t agree on the answers to those questions.

In a research article published last fall, UMass extension educator Elizabeth Garofalo and UMass professor Daniel Cooley wrote that the pathogen was first documented in Wisconsin in 1903, under a different name. Peter thinks it’s been around for a while but was mistaken for late-season apple scab. Srdjan Acimovic, a senior extension associate with Cornell University, thinks the fungal pathogen is new to North America. The Northeast has had wet summers in the past, he said, but the disease was not detected until 2017.

A Swiss research team that Acimovic collaborates with concluded that Marssonina coronaria was recently introduced to Europe, where it has emerged as a problem for the apple industry. Marssonina is known as the scab of summer in Asia, where it has been a problem in apples for a long time, Acimovic said.

Peter first detected marssonina blotch in Pennsylvania in September 2017. Rome Beauty and Red Delicious trees in one of her research blocks were defoliating rapidly, and on the leaves she noticed a distinct chlorotic pattern she had never seen before. She started hearing similar reports up and down the East Coast, where growing seasons have been progressively warmer and wetter.

Recognizing a potential threat to the apple industry, Peter started studying the disease more closely. For a while, she only noticed marssonina blotch on leaves. She finally found symptoms on fruit last year, in trees that were already heavily infested. She plans to investigate the slow-growing fungus in storage.

A good scab-control fungicide program can slow down, but not completely stop, marssonina symptoms. The “Achilles heel” is heavy summer rains that wash off fungicide just before harvest. That’s when the disease can really hit hard, Peter said.

“Some growers can be caught off guard, especially late in the season,” she said.

Orchard sanitation can limit pathogen buildup. Marssonina spores appear to overwinter in leaves on the orchard floor, though researchers are not exactly sure when the spores start flying or how exactly they infect trees. If growers remove leaves from the ground to prevent apple scab, they’re probably removing marssonina as well, she said.

Based on field trials, Peter found that Empire, Rome and “poor, poor Honeycrisp” are very susceptible to marssonina blotch. One of her Honeycrisp research blocks was “horrifically affected” by the disease, she said. Other susceptible varieties include Cameo, Fuji and Red Delicious. Gala is somewhat susceptible. Stayman, Cortland and Golden Delicious have shown moderate resistance. Scab-resistant varieties appear to be susceptible, too, which could complicate things for organic orchards.

Laboratory results from Cornell’s Acimovic, who has been studying Marssonina coronaria in concert with Peter, do not align with Peter’s orchard data. He found that Honeycrisp is slightly more resistant than Fuji, for example. He also reported one case of marssonina blotch found on organic Jonagold apples in storage. The blotch was found in February, though there was no sign of it when the apples were put in storage a few months before.

To combat marssonina, Acimovic recommends growers keep to a 14- to 21-day summer fungicide spray schedule. If there’s no rain after the previous spray, they can wait up to 21 days before applying the next spray. But if it rains more than 2 inches within any of those periods, growers should immediately reapply after the rain ends. Based on his lab tests, fungicide resistance doesn’t appear to be a concern in this fungal pathogen.

Acimovic said a European decision aid system, the RIMpro Cloud Service website at www.rimpro.eu, offers a predictive model for Marssonina coronaria that growers should use to predict the first infection of the season. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment