The climate of Northwest Michigan poses many challenges to wine grape growing, but there’s also great potential, according to the new viticulture extension educator Michigan State University hired last summer.

Esmaeil Nasrollahiazar started his position in Northwest Michigan in July. Though he hasn’t been on the job very long, he thinks the region has the potential to produce the best sparkling wines in the world.

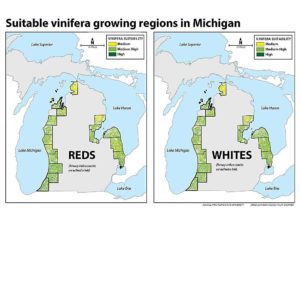

He laid out the challenges of growing those wine grapes during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market EXPO in December. More than 70 vineyards — about half the vineyards in the state — grow in the area better known for its tart cherries. Most of the region’s wine grape acreage is Vitis vinifera, traditional European cultivars not known for cold tolerance. Though Lake Michigan provides some protection from the cold, low temperatures damage those vinifera vines almost every winter. Polar vortex events, driven by climate change, occur more frequently. Cold damage and the region’s short, extremely variable growing seasons lead to variations in grape yield and quality, he said.

He made some general recommendations, including cultivating cold-hardy varieties, for dealing with the challenges:

—Canopy management. Remove leaves early to open up the canopy, which increases air ventilation and light penetration.

—Enhance soil fertility. The region’s sandy soils are good for grape production in many ways, but poor for vine nutrition. The ideal level of organic matter in the root zone is 2–3 percent. This can be achieved through compost applications. He also recommended mulching and frequent trunk renewal to maintain young, healthy trunks.

—Covered cultivation. Covering grapes extends the growing season, increases the accumulation of heat and protects vines at critical growth stages.

Nasrollahiazar took the position as viticulture extension educator in part because of a budding interest in cooler-climate viticulture. He said most of those recommendations can apply to other cooler-climate viticulture regions, though the sandy soils in Northwest Michigan are fairly unique.

Nasrollahiazar grew up in a farming and fruit-growing family in Iran and studied viticulture in Italy before coming to the United States. He came to MSU two years ago as a visiting scholar. He’s currently focused on trying to solve the cold-hardiness problem, but at some point he would like to establish a new vineyard at the Northwest Michigan Horticulture Research Center to study training systems.

One of the systems he would like to study, called Pergola Trentina, is used in the Trentino region of Northern Italy. Nestled in the Alps, Trentino’s climate is similar to Michigan’s, with cold winters and short growing seasons. Trentino produces “amazing” wine, however, yielding grapes with a higher level of Brix than in Michigan, where winemakers have to add sugar. Much of this fruit quality is due to the Pergola Trentina system, where grape clusters hang outside the canopy and get plenty of diffused light and good air circulation, he said. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment