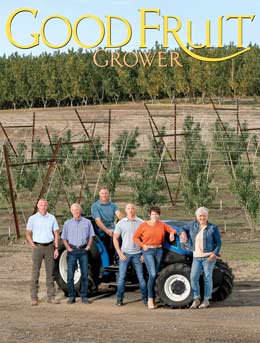

Peaches created Douglas Fruit, and peaches will be part of their future, the Douglas family said.

Eighty acres of young trees, planted in a V-trellis system to support mechanization, attest to that.

Douglas Fruit peaches and nectarines are “recognized as a true premium program” in the marketplace, said Mike Taylor, vice president of sales for Stemilt Growers, Douglas Fruit’s marketing desk. “Everyone will tell you that when peaches are good, nothing is better.”

The only peach worth picking at Douglas Fruit is a ripe one. But that philosophy leads to an average of five or six passes per block, maxing out near nine. That’s a huge labor cost, but it is just how peaches ripen, said John Douglas, head of orchard operations for the family company.

“Our window is probably two days,” he said. For the first couple of passes, he pays workers by the hour, to ensure they carefully judge maturity, but they often shift to piece-rate pay on the larger, later passes.

“There may only be two or three nice peaches ripe at the top at first. So that first pick costs a lot, but it’s your best fruit, and if you don’t pick it, you lose it,” he said.

Color guides the pickers, although for dark red varieties, it can be a challenge. The key, Douglas said, is the yellow background.

Douglas’s newer plantings, supported with a two-wire trellis, create a more uniform system to support “any kind of mechanization to reduce hand labor,” he said. In the older blocks without trellises, some leaders lean into the row more than others along each side of the V, making it too risky to use a hedger or blossom thinner.

“Our older styles, they weren’t uniform enough to utilize a platform,” he said, due to the wobble of the fruiting wall.

Training the V trees to a wire changes all that, and he’s slowly acquiring an “army of platforms” required to handle the many picking passes.

Douglas Fruit switched all of its stone fruit — peaches, nectarines and dwindling acreage of apricots — to organic management 15 years ago to differentiate its fruit from the California crop. It’s been a successful strategy in the market and the orchard, but when Douglas looks to the future, he is less confident than he used to be about the future of organics.

“The organic deal is getting really tough, and we have so few tools,” he said, referring to pest and disease control. “We basically have Entrust, that’s our silver bullet.”

Meanwhile, new pests continue showing up: oriental fruit moth, mealybug and spotted wing drosophila have posed problems in recent years.

Even with the labor costs and organic uncertainty, Douglas’ passion for his peaches is evident.

“My grandfather farmed peaches; my uncle farmed peaches. There was one point a few years ago when the apple market was really strong, and it was like, ‘Why are we farming all these peaches? Apples are easier.’ But it’s nice to be diversified when the apple deal gets tough,” he said. “I tell growers, ‘If you really don’t want to have any summer break from cherries to Pink Ladies, plant peaches and nectarines.’”

Here are a few more tips from John Douglas on modern peach production:

—Douglas prefers a V system instead of a traditional vase because it’s better suited to Washington’s growing climate, which doesn’t have quite as much vigor as California.

—He opts for an informal V because “the difference between peaches and apples is you grow fruit on 1-year-old wood. So, you can never tie anything except the leader for some structural support,” he said. “We’re constantly renewing.”

—Plantings start with a feathered nursery tree on Lovell rootstock, which they plant and then cut back to “start it all over and immediately start training them” into two leaders for the V system, Douglas said. Bamboo stakes guide the leaders until they reach the first wire and then keep them from resting directly on the wire.

—Workers need room to move around the trees, so the only supporting wires in the training system are at least 6 feet high.

—Crop load management is key. Douglas wants 120 fruits per leader, but different varieties require different approaches to get there. “We know from experience what varieties will set heavy and set light, so we prune accordingly,” he said. Some cultivars even call for blossom thinning, which crews will do by hand “very selectively.”

—“Peaches just like to die,” Douglas said, so he carefully watches his production numbers for each block to determine when older blocks have fallen below the cost of production and need to be replaced.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment