Tree fruit growers in Washington have been releasing natural enemies into their orchards, and this practice is becoming more popular as organic acreage expands. The practice started with moving predatory mites (“typhs”) from orchards where they were abundant to orchards where they were absent, by transporting tree cuttings, as early as the 1960s.

The establishment of the commercial insectary industry has taken the practice of natural enemy augmentation to new heights. In North America alone, nearly 40 companies are now selling about 70 different species of natural enemies for various pests. Once a grower has selected a species appropriate for controlling their pest, they have additional choices to make. Some species are sold in multiple life stages, with different price points per unit. Others can be delivered through multiple methods — for example: lacewings can come on cards; on cardboard hexcell units; and loose in containers, for sprinkling. Then, a decision needs to be made about how many natural enemies to purchase and when to release them. Depending on the natural enemy, growers even have the option to apply by contracting with a drone pilot.

In tree fruit, these decisions are made more complicated because current recommendations are based primarily on use in greenhouses, or low-growing crops like strawberries — very different environments from the growing areas of apples and pears in the Pacific Northwest. Commercial availability of particular species is driven by demand. Ideally, orchardists in Washington and Oregon would be able to purchase species that are native to the area, or at least well-adapted to hot, arid summers. Growers would also like species that can overwinter and establish, reducing the need to perform many releases each year. But the demand for these kinds of species is much lower (or nonexistent) in humid, climate-controlled greenhouses. Additionally, while there is some overlap in the types of pests found in greenhouses and orchards, there are also large differences.

For instance, some of the most common questions about beneficial insect availability for orchards are regarding parasitoids that have high host-specificity for orchard pests, such as Trechnites insidiosus (a pear psylla parasitoid) and Aphelinus mali (a woolly apple aphid parasitoid), and for parasitoid wasps that are more host-specific to codling moth than what is currently available. Not only is the demand for these biocontrol agents low relative to the current focus of the insectary market, but they can be more difficult to rear. That is because rearing their host often requires growing and maintaining large numbers of trees in a greenhouse setting, resulting in a logistically difficult and cost-inefficient operation.

Despite these difficulties, some orchard managers have been successful in using purchased natural enemies for pest management. These growers, and those looking to newly adopt these practices, need scientifically based recommendations that are tailored to the unique growing conditions of the Pacific Northwest. To kickstart these efforts, I am leading a project team with the goal of collecting both initial field data and documentation of grower needs to support an eventual much larger project. This work is supported by grants from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, the Fresh and Processed Pear Committee and the Western Integrated Pest Management Center. We also have excellent collaborators at Gebbers Farms (Mike Brown), Parabug (Chuck Weaver) and Biobee (Steve Arthurs), who have been instrumental in starting this research.

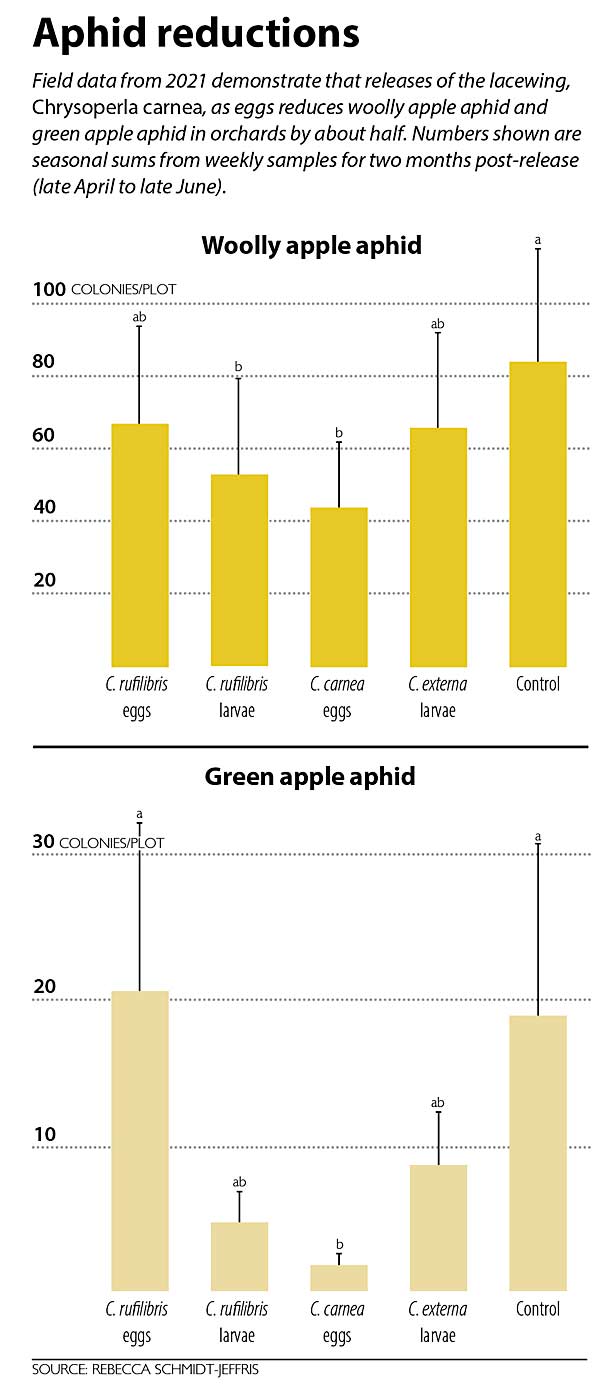

Our initial research efforts have shown that mealybug destroyers and lacewings can successfully reduce populations of mealybugs and pest aphids, respectively. Much more follow-up work will be needed to fine-tune recommendations for using these beneficial insects. In 2022, a postdoctoral researcher will work with Louie Nottingham (Washington State University) and me to expand this project and examine methods for retaining natural enemies once they are released, including the use of lures and food products such as sprayable pollens and brine shrimp eggs.

Currently, our extension team consists of Tianna DuPont (WSU) and Ashley Thompson (Oregon State University). Together, we have conducted a series of stakeholder input sessions on determining what the major barriers are for adoption and successful implementation of releasing natural enemies. Many growers agree that lack of knowledge on best practices (release rates, timing and which species to choose) is a big hurdle. Others have also advised that years with lower prices for organic fruit make releasing beneficials uneconomical, and labor costs also play a big role. Additionally, supply from insectaries can be limited and inconsistent.

In addition to those input sessions, we are still interested in hearing from you! If you grow tree fruit or serve as a pest management consultant in Washington or Oregon and have not yet done so, please fill out the following survey: bit.ly/Qualtrics-Survey.

We envision that natural enemy releases will continue to increase in popularity as options for organic pest control, alternatives for pesticides that lose registration or target pests with resistance issues, or even as zero-day preharvest interval alternatives in conventional orchards. They might best fit programs that have recently switched to organic or soft/IPM practices and need assistance getting over the typical three-year pest outbreak hump. Regardless, our growers need evidence-based recommendations that are specific to our industry. We are excited to get this information into the hands of our stakeholders.

—by Rebecca Schmidt-Jeffris

Rebecca Schmidt-Jeffris is a research entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service lab in Wapato, Washington, where she focuses on biological control of arthropod pests of tree fruit. She can be reached at rebecca.schmidt@usda.gov.

Leave A Comment