Seaweed extracts are typically used by growers with the aim of improving tree growth and enhancing fruit yields and quality. Although the extracts are regulated and marketed as plant growth regulators, entomologists have been studying whether the products could also have benefits in terms of pest control.

Seaweed extracts are typically used by growers with the aim of improving tree growth and enhancing fruit yields and quality. Although the extracts are regulated and marketed as plant growth regulators, entomologists have been studying whether the products could also have benefits in terms of pest control.

Results of a study conducted in Washington State suggest that seaweed extract applications can reduce pest mite populations. However, in experiments in Vermont, the extracts had little effect on the incidence of mites or most other pests, but did reduce fruit damage from apple maggot on some apple varieties.

Dr. Holly Little, market development scientist with Acadian Seaplants, Ltd., in Nova Scotia, Canada, which markets Stimplex (containing extracts of the seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum), has been collaborating with Dr. Alan Knight, entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Yakima, Washington. She presented preliminary results of their ongoing trial during an International Organic Fruit Symposium held in Washington last summer.

Little said seaweed has been used for many years in agricultural production. Native Americans recognized the advantages of using seaweed as a mulch or fertilizer and used to gather it from the shoreline and apply it to their crops. Since the 1960s, farmers have been using commercial products containing seaweed extracts as foliar sprays or ground applications.

The idea of testing seaweed’s effects on mites came after growers who were using the seaweed to enhance tree and fruit growth reported seeing fewer mites in their orchards, Little said.

Washington

The Washington experiment began in 2011 in two orchards at Moxee near Yakima. One was a commercial apple and pear orchard and the other a USDA research plot with just apple trees.

Treated plots in both orchards received season-long applications of Stimplex. Sprays were applied at the tight cluster, pink, and petal fall stages of bloom, followed by three monthly applications.

The USDA orchard was treated with pheromones for mating disruption of codling moth, and no other sprays were applied. The commercial orchard was treated with six pesticides in addition to pheromones.

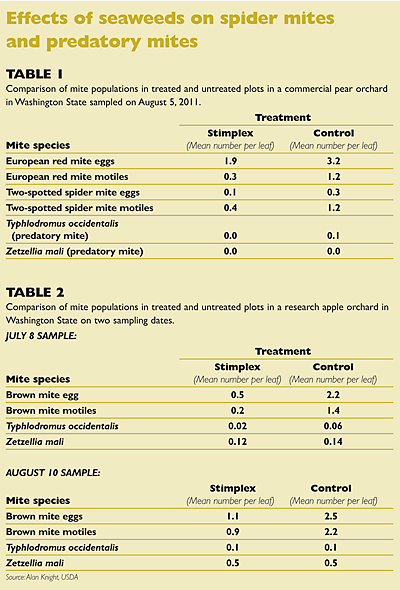

Leaf samples collected four times during the season showed a general trend of fewer mites in the Stimplex-treated trees in both orchards. However, in the commercial orchard, statistically significant differences were seen only in an August sample. European red mite populations exceeded economic thresholds in both treated and untreated trees by the end of the season, which Little attributed to the pesticides applied to that orchard.

At the USDA orchard, the Stimplex-treated trees had fewer brown mites in July and August (Table 1). There were no statistical differences between the populations of predatory mites (Typhlodromus occidentalis and Zetzellia mali) in either orchard. The trial is continuing in 2012.

According to Ashlea Barr, corporate communications officer at Acadian Seaplants, research into the mode of action of the seaweed extracts on insects, including mites, is ongoing. Previous work has indicated that reductions in mite populations may be due to improved plant health and increased resistance to a variety of environmental stresses in plants treated with the extracts. In addition, studies have shown that mites prefer to feed, settle, and reproduce on untreated plants.

Vermont

Terence Bradshaw, research specialist with the University of Vermont, conducted tests in 2009 and 2010 in an organic apple orchard at the research center in South Burlington to compare Stimplex and SeaCrop 16 (an A. nodosum extract from North American kelp) with an untreated control. The two products claim improved resistance to damage from diseases and insects on crops, including apples, in their promotional materials. The trial had five different cultivars: Ginger Gold, Honeycrisp, Liberty, Macoun, and Zestar.

The treatments were applied according to the manufacturers’ guidelines. Seven applications were made each season. The foliage was assessed in late July and early August for incidence of European red mite, two-spotted spider mite, predacious mites, leafhoppers, lady beetle larvae, black hunter thrips, and cecidomyid fly larvae. Leaves were also evaluated for damage by Japanese beetle, leafhoppers, and leafminers. Fruit was assessed for injury by plum curculio, tarnished plant bug, apple maggot, European apple sawfly, codling moth, oriental fruit moth, lesser apple worm, and leafrollers.

There were no differences in the populations of predacious mites, cecidomyid fly larvae, or lady beetle larvae. In 2009, black hunter thrips, a predator of phytophagous mites, were found on fewer leaves on the Stimplex-treated trees than on the untreated trees. However, there was no effect on pest mite populations.

“Therefore, the A. nodosum extract materials studied in this experiment do not appear to provide any benefit in phytophagous mite management compared to the nontreated control,” Bradshaw reported.

Mite populations were high throughout the orchard, Bradshaw said. The orchard was managed with an intensive, organically acceptable spray program for scab and insects that is typical for a Northeast orchard and included applications of sulfur or lime sulfur as well as kaolin clay. Those materials are known to negatively impact predatory mites and have been shown to lead to flare-ups of phytophagous mites.

Fruit damage

The seaweed extracts did not affect the amount of fruit damage from European apple sawfly, plum curculio, codling moth, oriental fruit moth, lesser appleworm, or leafrollers, or the incidence of those pests in either year. In 2009, Stimplex-treated trees had a greater incidence of leaves with lyonetia (apple leafminer) mines than the untreated trees.

In 2009, some varieties in the control plot had fruit damaged by apple maggot, whereas the seaweed treatments had none. In the control plot, Honeycrisp and Macoun also had no damage, but Ginger Gold had 0.7 percent fruit damage, Liberty 1.3 percent, and Zestar 0.7 percent, for an average of 0.5 percent across cultivars.

In 2010, Honeycrisp in the control plot had 4.8 percent apple maggot damage, but the rest of the control varieties had none. Trees treated with the seaweed products had no damage.

Although reductions in apple maggot incidence resulting from the treatments were noticeable, the pest pressure was sufficiently low, even in the untreated control, that reductions in damage would not be economically important, Bradshaw said. He believes the seaweed extracts might be altering or masking the scent of ripening fruit, which the apple maggot flies use to locate fruit to infest.

Bradshaw concluded that use of seaweed extracts could not be recommended as a way to improve pest management in an organic apple orchard. However, further research on the effects of the materials on apple maggot in an orchard where there is higher pest pressure could be warranted.

Leave A Comment