Wildfire has dramatically increased the risks for grape growers in the West. Smoke concerns following California fires in 2021 led to a raft of grape rejections by wineries, in part due to mushy language in contracts written before wildfires were such a threat. And the lack of a reliable standard lab test for smoke taint bedevils wineries and growers alike.

“The more real data is out there, the more people can expect to have precise language in contracts,” said Anita Oberholster, University of California, Davis extension specialist in enology, at the Unified Wine and Grape Symposium held in Sacramento in late January.

She and other scientists are hustling to discover how to protect grapes and predict smoke risk well before wine is made, but many answers are years away — and in the meantime, growers need to protect their vines and their businesses. Oberholster and her fellow panelists offered growers advice on how to approach testing, contracts and crop insurance while the science catches up.

State of the smoke science

First, a chemistry lesson: Smoke taint comes from volatile phenols, or VPs, released by burning wood. These “free VPs” get into grapes through their skins, Oberholster said, and some bind to sugars to create compounds called glycosides.

Free VPs, such as guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol, are primarily responsible for the bad taste initially, but bound VPs matter because they break down into free VPs during fermentation. So, labs may test for either, both or total volatile phenols. Oberholster’s advice:

—Stick to the same lab for comparable results; methods can vary. And note the fine print: Labs will typically report a range of acceptable standard deviation for a compound’s test results. Within that range, results can be considered equivalent.

—Where there’s smoke, do microfermentations. Because the smoke expression changes with fermentation, microfermentation is a tool wineries can use to make quick decisions about whether to pick or not, especially if labs are backlogged. Oberholster recommends that for any smoke exposure, save 300-gram berry samples, ideally before and after exposure, and freeze some for future reference.

Then, do small-lot fermentations of 30–40 clusters, one per vine. It’s easier to taste smoke impact over 23 Brix, and larger samples will be more representative. Smoke impacts may take six to nine months to show up in finished wines, and sometimes quality is affected without specific smoke characters emerging. But a microfermentation will often reveal problems within a few days.

Establish a process for evaluating wine. Focus on just the palate, because the nose is too sensitive to other things. “Ashtray, campfire, cigarettes, tar — it has to be smoke-related, not just random bitterness,” Oberholster said.

(Read more on how to do microfermentations, from the West Coast Smoke Exposure Task Force, at: bit.ly/microfermentation-protocol.)

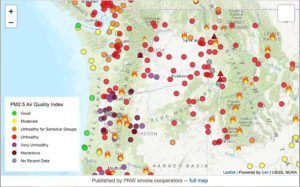

—Which grapes are at risk isn’t easy to tell. Neither your nose nor the air quality index focused on human health risks offer a good measure of the risk smoke poses to grapes. Fresh, dense smoke is by far the worst, but smoke events are so variable that there’s no such thing as a standard safe distance from a fire, she said. And ash can release volatile phenols for up to a week.

To complicate matters further, berries may be susceptible at any stage of growth, and some cultivars appear more sensitive to smoke exposure than others.

—Sprays may help. But which ones? Kaolin clay has shown mixed results in trials, and it may depend on bunch structure and coverage — as well as whether the coating, which absorbs the smoke volatiles, is washed off before fermentation, according to Washington State University wine science professor Tom Collins. Biofilms used to keep other fruits from cracking helped some when sprayed a week before exposure, but less so when applied a day before it. Some sprays may make grapes more vulnerable to smoke — that’s what one British Columbia study found with a fungicide.

Oberholster is analyzing results from a trial in which she dipped grape bunches in 12 different spray solutions, exposed them to smoke and waited a week.

“I don’t think we’re going to have a golden bullet,” she said. “We will have things we can do to reduce the impact of the problem — and we will be able to make a decent wine even with some smoke impact.”

Know your contract

On the business side, Napa-based wine industry lawyer John Trinidad recommended ways to prevent disputes over grape contracts.

“At the heart of contracts is an allocation of risk,” Trinidad said. “This is definitely much more than just how and when you’re going to get paid.”

His tips for grape growers:

—Examine grape quality provisions. Older contracts that predate wildfire risks often aren’t specific enough. Agreements should consider smoke taint explicitly, separate from MOG-type (material other than grapes) defects. Contracts should set out a clear process and standards for rejection and, ideally, include a price adjustment mechanism short of flat-out rejection. They can also allow for delayed inspection and determination on acceptance, which gives growers a chance to show their grapes are good and wineries a chance to get some wine out of that harvest.

—Examine force majeure provisions, which triggered many disputes in recent years. These provisions allow a party to walk away with no damages in extreme situations beyond their control and that prevent them from fulfilling the contract. What situation is germane depends on each party’s role in the contract. For a winery, force majeure might be invoked if evacuation orders prevent it from accepting or processing fruit; for a grower, it would include being unable to harvest the fruit or provide the agreed-upon quality of fruit.

—Negotiate amendments for smoke risks, if you’re already in a multiyear contract that doesn’t include them.

—Prepare a backup plan through the bulk market, in case grapes are rejected, and consider who covers the crush costs.

—Maintain good communication with your buyers. “The better relations you have with your contract partner, the more likely that there will at least be an agreeable outcome in tough situations,” Trinidad said.

Know your crop insurance

Since crop insurance is the main recourse for growers with smoky grapes and winery rejections, get to know your policy before a plume arrives, said insurance agent Kristine Fox of Pan American Insurance. Her advice:

—Not all carriers are equal. Although crop insurance is federally regulated and the premiums cost the same no matter where you get it, the details can differ. There’s no federally designated numeric standard for exposure; the current term is “elevated,” and it’s up to the carrier to define it.

“Make sure you’re working with a carrier that’s grape grower-friendly,” Fox said.

—Act quickly. When smoke comes, err on the side of filing a claim — within 72 hours of damage, Fox said. Like Oberholster, she recommended collecting grapes, clearly labeling them and testing immediately. Both grape and wine samples are accepted, which is useful since wine will sometimes reveal smoke problems that grapes did not.

Once a claim is submitted, a claims adjuster will count bunches at the vineyard. Unharvested tonnage may result in a lower payment. Since grapes are insured for tonnage, not value, the adjuster may apply a “quality adjustment factor” to convert the loss of income from smoke taint into a tonnage loss.

Fox noted that U.S. Department of Agriculture Risk Management Agency staff are working on smoke-related updates. They’re reevaluating the unharvested cost deduction and distinguishing between machine-harvest versus by hand. They’re also creating a smoke endorsement modeled on hurricane coverage.

Growers can also consider Whole Farm Revenue Protection, a form of crop insurance that, as the name implies, insures by average revenue, not yield. Under this approach, growers can insure against market price loss. It is often useful for those who grow both white and red grapes, Fox said. And Congress recently poured another $10 billion into the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program Plus, a fund that helps farmers offset the cost of natural disasters. Winegrowers who can prove losses for 2020 and 2021 can get up to $125,000.

A cautionary tale

Grower Mike Boer had a story about that. After the Mendocino Complex Fire ripped through a vineyard he leases in the Ukiah-area, in 2018, smothering his grapes in fresh smoke, his lab tests were suspect and his winery handed him a rejection letter.

Instead of filing a crop insurance claim, Boer experimented with some microfermentation. At first it seemed promising, so he made bulk wine. But by April 2019, the wine tasted “funky,” he said. “It didn’t have smoke problems, but it wasn’t good.”

WHIP+ rescued him, he said.

“I got $125,000 to make me whole and cover me for being an idiot,” he said, urging growers to learn from his experience. Looking back, he said, “the smart thing would have been to file a claim.”

—by Kate Golden

Leave A Comment