Stop in any American grocery store and you can expect to find the usual apple suspects: Honeycrisp, Gala, Fuji. But visit a Safeway in Yakima, Washington, and you’ll also find promotions for Envy, Cheekie and Rockit. Across town at Walmart, there’s Koru and Jazz. And for a few weeks at Costco: WildTwist.

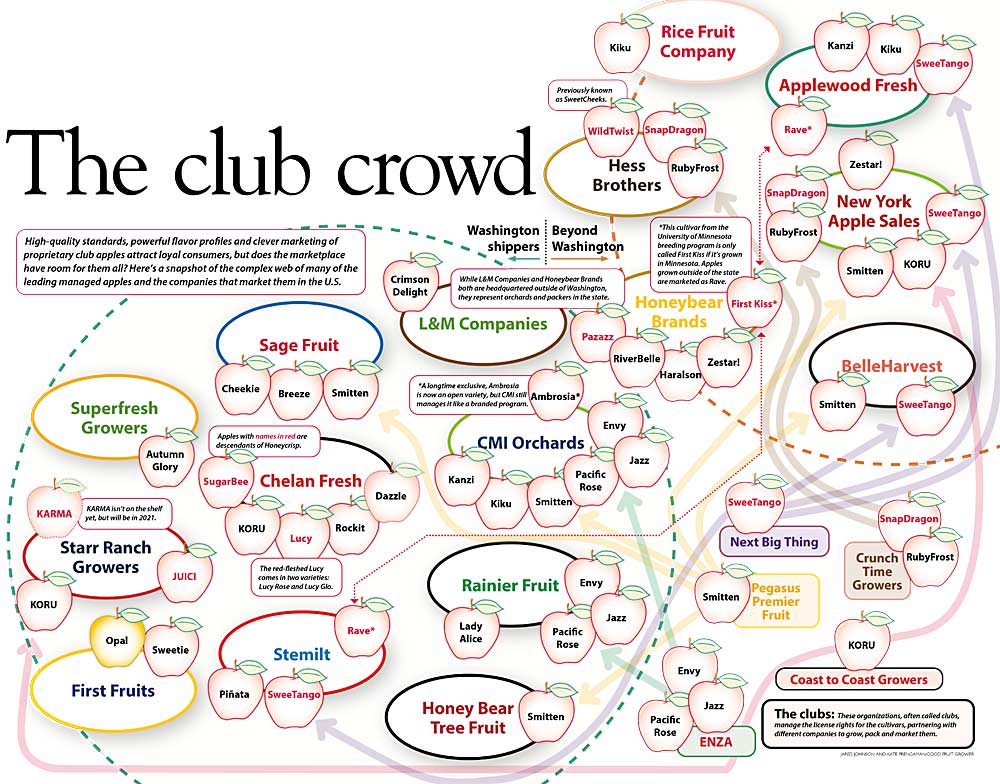

Major retailers pushed for new, high-quality varieties as a top priority a decade ago, and apple shippers more than delivered. Today, dozens of managed brands compete for the small slice of premium purchasing in the apple category — a blur of brand-named, bicolored apples grocers say confuse them and their customers.

For growers, it can be hard to look at this landscape and know what to plant. There’s both risk in planting a speculative variety and risk in sticking with the commodity apples. But to make the best decisions, growers should look beyond the orchard and learn how the shippers they work with (or want to work with) plan to position and promote their apple brands for success over the coming decade that is expected to bring more competition and consolidation.

“There’s definitely going to be some shakeout going on with the managed varieties,” said Bob Mast, president of CMI Orchards. But at the same time, “the real growth in the apple category at retail is really coming from managed varieties, organics and Honeycrisp.”

“In virtually every consumable product category, over time the quality goes up and prices go down. In the apple category, we are going to produce better and better apples and the price of those will get commoditized over time.”

—Steve Lutz, Category Partners

The next few years may mark a turning point in the trend of variety proliferation that began as the Washington Apple Commission’s domestic marketing program dismantled in 2003, after which each marketing desk sought to differentiate. Add to the crowded retail shelf a new heavyweight in Cosmic Crisp, declining prices and pandemic-driven recession, and many companies now say they are treading cautiously when it comes to building volume for existing brands. They’re also heavily scrutinizing apples of the future — those already under observation in variety trials.

“We’ve probably hit the breaking point in terms of the number of SKUs or apple varieties that a retailer is going to carry,” said John Onstad, director of sales for Sage Fruit Co. “I think there are too many: Most will go by the wayside or become a niche, and the winners will become an everyday apple, displacing something else.”

But Sage is also cautiously investing in a new apple, the Cheekie, already grown and marketed by its partner, New Zealand-based Freshco, Onstad said.

That’s the paradox: There may be pushback from retailers on variety proliferation, but new varieties represent the industry’s primary path to growing better apples and bigger returns.

Some industry observers predict that pressure from those large retailers will force further consolidation among Washington sales desks. An August report from investment bank Cascadia Capital predicts that the 10 or so major players may be down to just four or five in coming years — a prediction Cascadia co-founder Michael Butler shared at the U.S. Apple Association’s annual meeting.

—Desmond O’Rourke, Belrose Inc.

Of managed apples and mergers

The strategy of managed scarcity and tightly controlled quality to keep prices high worked better when there were just a handful of managed apples, not several dozen competing for the same sliver of shelf space, said Steve Lutz, senior vice president at consulting firm Category Partners.

“The winners will be those with the strongest marketing, because it’s not like any of these are bad apples,” Lutz said.

Apple industry economic analyst Desmond O’Rourke likened the current retail environment to survival of the fittest for both the varieties and the desks that sell them. Retail consolidation pushes supplier consolidation, he said.

“The marketers are very much at the mercy of the retailers,” he said, because they now have so many good apple options. For example, he recently saw WildTwist apples, packed by Hess Bros. Fruit Co. in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in a Pacific Northwest Costco.

That program is growing, with orchards in Pennsylvania, New York and, soon, Washington, thanks to a partnership with Rainier Fruit, said Hess Bros. marketing director Chris Sandwick. Such cooperation marks a “smart move,” Sandwick said, in that the parties can work together and cater to large national retailers.

More mergers could pare down the industry’s managed apple portfolio. Similar consolidation trends across the food industry appear to drop weaker-performing brands, O’Rourke said, but for apples it gets complicated.

“It’s easy for Coca-Cola to simply stop buying sugar, but when you are an apple marketer and you have a bunch of growers growing all these varieties, you can’t ditch them; you are stuck with them for years to come,” he said. “That’s something the retailers don’t understand or choose not to understand: There is enormous investment in these new varieties. The ingredients are already in the ground.”

“There’s a lot of chatter out there that as a state we’ve oversaturated the market with all of these bicolored red apples. But we’re all still looking for that next great thing.”

—Jim Hazen, First Fruits

The Honeycrisp high

Honeycrisp, of course, first proved that consumers would pay more for a better apple, giving rise to the premium apple push.

But Honeycrisp cannibalized its own, said Fred Wescott, president of Wescott Agri Products and Honeybear Brands, who helped pioneer Honeycrisp’s expansion beyond its Minnesota roots. The profitability inspired more and more people to plant it, even in places not well-suited to growing the notoriously finicky fruit, and now oversupply and variable quality are depressing prices.

Managed apple programs aim to avoid that fate, but Honeycrisp has long served as the gold standard for premium apple prices, proof that the investment in development, production and promotion of new apples could pay off, Wescott said. Marketers used the Honeycrisp price ceiling to introduce another variety by offering consumers a chance to try something new for a little less, Lutz said.

“As the Honeycrisp market declines, it puts that model in jeopardy,” Wescott said, adding that Honeybear is being more cautious about commercializing potential new varieties, “because a lower price point per pound of fruit changes the model.”

Declining Honeycrisp prices also offer premium varieties an opportunity, said Mast of CMI. The core varieties can’t make up retailers’ lost returns on Honeycrisp dollars, so they need more high-priced managed varieties that can, he said. To wit, CMI is investing in more organic Kanzi and organic Envy next season.

All apple varieties are sensitive to supply and demand, said Jim Hazen, CEO of First Fruits, which markets the Opal. Demand is strong for the yellow apple that stands out among the bicolored brands, so First Fruits is looking to partner with outside growers to increase the volume, albeit carefully.

“That is a huge advantage in a managed program, so you have the opportunity to walk that fine line of supply and demand and keep a price point at a premium level,” Hazen said.

For ENZA, the global club that manages Envy, Jazz and Pacific Rose on behalf of owners T&G Global of New Zealand, the market pressures mean U.S. growth is strategic, said Rick Derrey, director of horticulture for North America.

“We’re obviously not immune to the marketplace,” Derrey said, adding that the club does benefit from strong brand recognition. “We see challenges in the apple category for the next few years, however we’re well positioned to maintain a premium spot, especially with Envy.”

“Whenever you have an apple as massive as Cosmic Crisp, it will have a cannibalizing effect, but what varieties will it displace the most?”

—Bob Mast, CMI Orchards

On Cosmics and critical mass

Now, Cosmic Crisp orchards are coming into production at unprecedented volume. Eventually, the apple will likely take shelf space from Washington mainstays such as Red Delicious and Gala — but with a significant marketing budget behind it, Washington growers will also compete for promotional space with their own premium apple brands, Mast said.

“Cosmic Crisp is a huge disruptor on an order of magnitude I don’t even want to put a number to,” said West Mathison, president of Stemilt Growers, citing its quality and productivity. “Cosmic Crisp has forced us to reconsider success. If you have a lot of Cosmic Crisp, it’s going to be fun, but it’s going to be a hard time to introduce a new variety.”

To navigate around that, Stemilt bet on early apples, Rave and SweeTango, which hit the market in a less competitive window, he said, while another program, Piñata, is winding down.

Other marketers are similarly seeking a lasting niche where they can stand out from the crowd, be it with color, flavor or regional resonance.

Wescott said that having both national and regional programs bolsters his company’s growing and marketing programs. Honeybear markets Pazazz (which it grows in multiple regions) nationally, but it promotes RiverBelle, a regionally grown proprietary variety, in the upper Midwest.

A sense-of-place promotional approach also works for New York exclusives SnapDragon and RubyFrost, said Kaari Stannard, president of New York Apple Sales, which markets them nationally. Every retailer has a different definition of “local,” she said, but New York-grown apples appeal to people who have ties to the state but now live across the country.

Clubs or partnerships help to increase production — ensuring the volume necessary to keep consumers’ attention — and spread out risk inherent in planting something unproven, Stannard said.

“We’re finding our way,” she said. “We are spending a lot of money behind marketing to help our retailers sell more apples.”

“When we look at growers, we need to maintain diversification. Everything is risk and reward. You have to have some of your acreage in the higher f.o.b. — it’s about balancing your portfolio.”

—Kaari Stannard, New York Apple Sales

The ever-higher bar

The high and increasingly risky odds haven’t deterred the hunt for the next great apples. Rather, they’ve raised the bar for what’s worth the risk.

“The marketplace today is different than when each one of us said, ‘Yes, I want to bring this new apple to market,’” Mathison said, pointing out that most new apples spend a decade or more in commercial development. “The challenge is that I have so much invested, but I have so much more to invest to potentially become successful. That question is being pondered by every major marketer and breeding program around the world.”

Flavor rules, but price deflation puts a greater emphasis on productivity and packouts than the model Honeycrisp inspired, Wescott said.

“Cosmics can be commercially viable at a lower price point because of the productivity,” Wescott said. “The perfect pot of gold is can you find that next Honeycrisp that’s got great ease of production and low cost of productivity.”

Catherine Gipe-Stewart of Superfresh Growers agreed, saying that for an apple to be successful today it needs to be easy to grow and offer high packouts, in addition to standout flavor, mouth feel and shelf life. The company’s Autumn Glory program checks all those boxes, justifying its ongoing expansion, she added.

Starr Ranch Growers plans to introduce a new apple, KARMA, next season. In addition to an appealing flavor, its consistent, grower-friendly production is part of the allure, said Jeff Cleveringa, head of research and development for the company.

“Other industries bring new products in and take away old ones, but we are asking the market to choose for us. The fact that we are changing is good, but we need to change faster. If we want these new varieties to succeed, we need to give them more runway and more shelf space.”

—Chris Sandwick, Hess Bros. Fruit Co.

“We have to make money at the grower level,” he said.

Despite the much-discussed competition, he points to retail data showing that most managed varieties are seeing double-digit growth, not signs of saturation. “The big-picture data shows us consumers are willing to keep trying new things, then when they find one they like, they stick with it,” Cleveringa said.

It’s not just apple genetics that face a higher bar; orchard execution must excel, too.

“We made some mistakes and learned a lot in the first few years of SweeTango. We got forgiven because it was 2010 and there were a handful of varieties that were new, but there would be zero tolerance today,” said nursery owner and SweeTango grower Dale Goldy. “To me, for the new variety that’s going to be introduced, we have to really look at what our execution level is going to be and make sure it is absolutely stellar.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment