Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

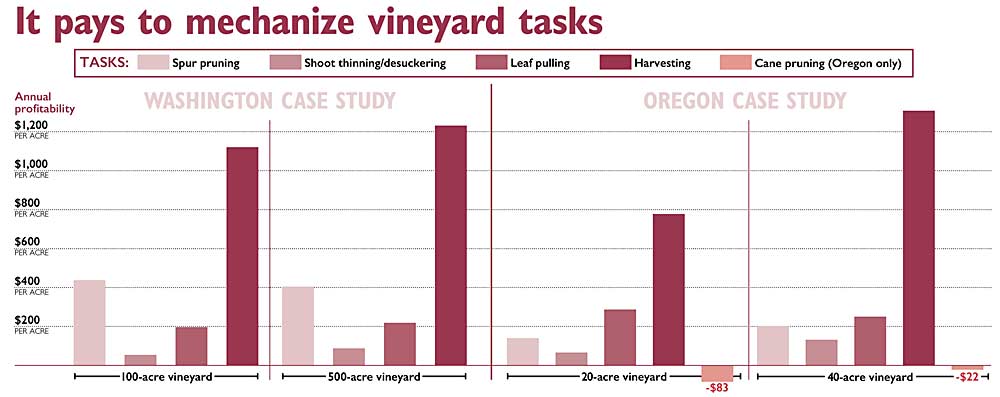

No matter the chore, no matter the state, whether large or small. It nearly always pays off to mechanize vineyards these days.

That’s the conclusion from Clark Seavert, an Oregon State University agricultural economist, who recently crunched the numbers in a study comparing the profitability of mechanizing routine vineyard tasks with using hand labor on vineyards of varying sizes in Oregon and Washington.

In almost every case — cane pruning was the only exception — net cash flow per acre per year ended up higher with mechanization. The results prove to him that growers must look beyond the sticker shock of expensive equipment when making decisions, evaluating profitability as much as financial feasibility, Seavert said.

“Everybody says, I can’t afford to do it,” Seavert said. “That’s all you hear.”

Seavert advocates a different way of looking at the financial outlay for expensive equipment, rather than focusing only on how long it takes to pay it off.

Seavert compared projected net returns of tasks over 10 years on case-study vineyards of 20 acres and 40 acres in Oregon and 100 acres and 500 acres in Washington. Oregon viticulturists typically work on a smaller scale than their neighbors to the north, where mechanization already has made a bigger impact.

To determine profitability, Seavert calculated the “net present value” of mechanizing each vineyard task, which is the difference between cash inflows and cash outflows over a period of time. “Cash flow is king,” he said.

Seavert did not dismiss the cost of paying off an expensive piece of equipment. He tracked it as part of the outflow and labeled it as the “payback period,” right next to his profitability conclusions.

He analyzed equipment ranging in price from $30,000 for a leaf puller towed behind a routine $75,000 tractor to a Pellenc tractor, harvester and precision pruner combination worth $470,000. Seavert only calculated profitability of that expensive choice for the 500-acre Washington vineyard. Payoff times ranged from less than a year to 25 years, depending on the size of the vineyard operation.

In spite of the payback period, however, all but one of the chores he compared showed profitability each year when mechanized, even if the machine wasn’t paid off by then.

The project was funded by $30,000 in grants from the Washington State Wine Commission and the Erath Family Foundation, a Portland, Oregon, research and education nonprofit named after the Dundee, Oregon, winery. It’s the first project to receive direct funding from the Wine Commission, said Melissa Hansen, research program director. Normally, the commission sends money to a statewide grape and wine research program that funds competitive grants.

Seavert has been giving presentations of his work and will share details in an upcoming webinar.

He has plans for follow-up studies to run similar economic assessments of leasing equipment, as well as gauging the financial implications for a business’ liquidity, solvency and repayment capacity when purchasing, leasing, custom hiring or perhaps sharing equipment purchases and maintenance with neighboring growers.

His work is similar to what some vendors do for customers, said Grant De Vries, a sales representative for Vine Tech Equipment in Prosser, Washington. De Vries, one of several industry collaborators on Seavert’s work, has his own spreadsheet to calculate costs for clients.

The results are informative, but each grower is a little different because each grower uses machines slightly differently, De Vries said.

Among Seavert’s findings:

—Mechanization would not be profitable for a vineyard using cane pruning as a training system in Oregon, where cane pruning is more common than in Washington.

—For growers of either 20 acres and 40 acres in Oregon, hiring custom operators would be more profitable than purchasing equipment for almost all tasks. Only for harvesting on a 40-acre vineyard would purchasing their own equipment show more profitability.

—In Washington, mechanization of all but one vineyard task would be more profitable than using hand labor, with less than two years to pay back the equipment. Shoot thinning and desuckering would have a six-year payback period for a 100-acre vineyard. •

—by Ross Courtney

Webinar

Visit bit.ly/mech-webinar for instructions on how to participate in Clark Seavert’s vineyard mechanization webinar, “Developing economic and financial benchmarks for mechanizing Northwest vineyards,” slated for 11:45 a.m. to 12:45 p.m. June 11. A phone-in only option is available.

Related: Should you spend now to save later?

Leave A Comment