There’s probably not much worse for an apple grower than putting a fine-looking crop of Honeycrisp into storage, only to find it so riddled with bitter pit a couple of months later that it can’t be sold.

Honeycrisp is notorious for its bitter pit problems but is too profitable for growers to give up. They need an accurate way to predict which blocks will yield unacceptable levels of bitter pit, so they can make their storage and marketing decisions accordingly.

Or, as Joel Crist, a grower and packer in New York’s Hudson Valley, put it: “I don’t want to put one of those 50-percent bitter pit time bombs on a truck headed to a grocery store.”

Researchers have developed a variety of prediction models for the postharvest disorder but are still gauging their accuracy. There’s Penn State University’s predictive model, Michigan State University’s leaf nutrient prediction method, and a couple of Cornell University approaches: peel sap analysis and passive prediction. All four methods have shown some degree of efficacy, but results can vary by region and year, said MSU apple production specialist Anna Wallis, who’s studying the methods in Michigan.

While none of these tools is perfect, Cornell horticulturist Terence Robinson is urging growers to layer several approaches, including the passive prediction method and the peel sap test, to make the best decisions. Last year, he and Cornell colleagues collected samples from hundreds of orchards to make the case to growers that the tools are worth using. The Cornell team plans to gather data again this year, and to work more closely with storage and packing operations to segregate fruit, he said.

Cornell research associate Yosef Al Shoffe, a member of professor Chris Watkins’ postharvest physiology program, has been trialing the passive prediction model for a few years, as part of the program’s efforts to create comprehensive bitter pit management recommendations for growers. Funding for his studies was provided by the New York State Apple Research Development Program and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Using the passive prediction model, a sample of apples (100 fruit from at least 10 trees in a block) are picked about three weeks before anticipated harvest and kept at 68 degrees Fahrenheit. One or two days before the block is slated for harvest, the sample is evaluated for bitter pit. The percentage of bitter pit in the sample should indicate the percentage of bitter pit that will emerge in the block it came from, Al Shoffe said.

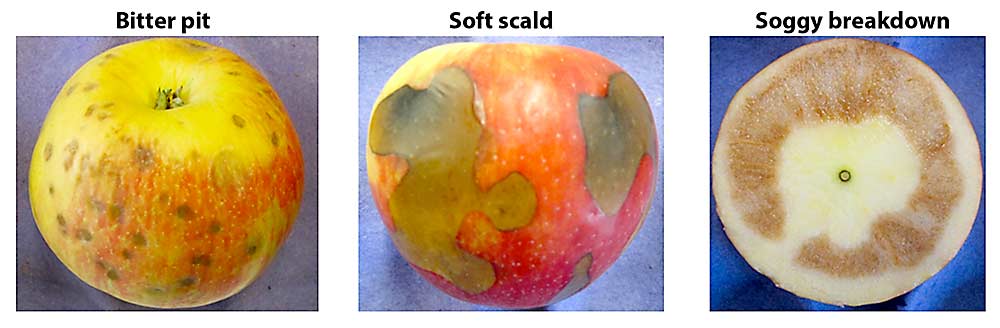

Fruit with a predicted bitter pit risk of less than 10 percent can be stored long-term or marketed immediately. If the predicted risk is greater than 30 percent, fruit should skip the conditioning step and instead move to rapid cooling and storage at 38 degrees. Honeycrisp is typically kept at 50 degrees for a week (conditioning) to reduce the risk of soft scald and soggy breakdown, but waiting to cool the fruit can contribute to bitter pit development. It’s a tricky balance, Al Shoffe said.

Results of passive prediction model trials have varied from state to state. Washington state trials haven’t been predictable, in line with a review of other methods by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which found that none of the predictive approaches works well enough for Washington-grown fruit. But Pennsylvania results have been extremely precise, Al Shoffe said. In the second year of New York trials, the passive model underestimated the final percentage of bitter pit, but plant growth regulators applied to the blocks after samples were picked might have exacerbated incidence of the disorder, he said.

Crist, the Hudson Valley grower, has tested the passive prediction model at his storage facility. Honeycrisp is the only variety he grows that has major bitter pit issues, but he doesn’t have a lot of experience with its long-term storage because he sells most of his Honeycrisp the first few weeks after harvest. He anticipates a greater need for long-term Honeycrisp storage in the future, however, and said he wants to know which prediction method will work best in his region.

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment