A new bitter pit prediction strategy developed at Cornell University aims to give New York Honeycrisp growers insight early enough to adapt their management or marketing plans to mitigate that risk.

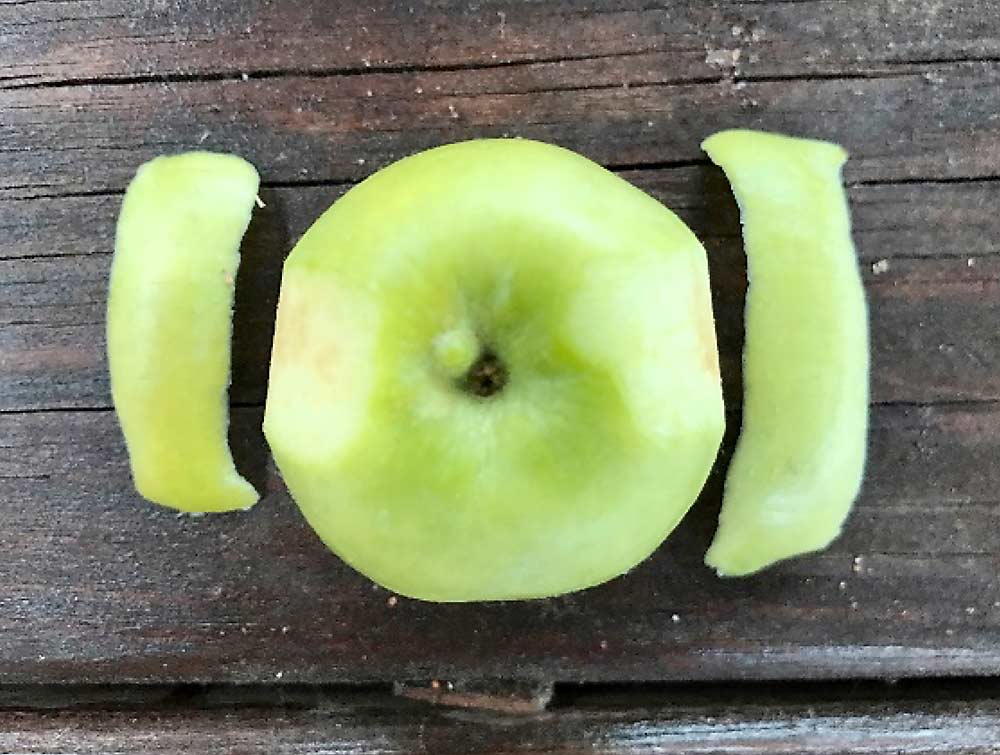

By taking peel samples from golf-ball-sized fruit in early July and measuring nutrient levels in the juice squeezed from that peel, scientists can measure the levels of key nutrients, including calcium, potassium and magnesium, and return results more quickly than existing nutrient analysis approaches, said Cornell Cooperative Extension fruit specialist Mario Miranda Sazo.

The new method marks a “breakthrough because of its simplicity,” according to Cornell postharvest physiologist Chris Watkins, who also studies bitter pit but was not involved in developing this approach.

Calcium levels, and more specifically the ratio of calcium to other nutrients that compete with it, has been the focus of bitter pit research for years. It is also a key component of other prediction approaches, such as one introduced by Penn State University a few years ago that relies on dried peel samples from fruit picked three weeks before anticipated harvest.

“The advantage of this over traditional dried peel tests is you can get the information to growers two months before harvest,” said Lailiang Cheng, the Cornell physiologist leading the peel sap project. The researchers use a technique known as inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectrometry to directly measure the nutrient content of the juice more quickly than traditional techniques that require samples to be dried and digested before nutrient analysis, he said.

“If a block is identified as high risk, they can implement more calcium sprays (during the season), or at harvest time, the growers may not want to apply Harvista or ReTain because those may exacerbate the bitter pit risk,” Cheng said.

The peel sap push

Cheng and Miranda Sazo began working together on bitter pit research in 2015, and in 2017, Miranda Sazo began his doctoral project in Cheng’s lab, assessing Honeycrisp’s unique nutrient requirements. Building on that work, they partnered with Western New York’s largest packer, Lake Ontario Fruit, and Mike Rutzke, director of the Cornell Nutrient Analysis Laboratory, to examine how best to test Honeycrisp to predict bitter pit.

After three years of trials, it was clear the peel sap method offered the most robust results, and in 2020 the Cornell tree fruit extension team encouraged growers across Western New York to send in samples. They tested over 200 blocks and found that a ratio of potassium to calcium over 25 indicated higher risk of bitter pit.

Cheng said that with this peel sap approach, that ratio seems to explain about 70 percent of the variation in bitter pit. Adding other nutrients, such as magnesium, can inch that a few percentage points closer, but it still doesn’t explain all the variation. He hopes that a new technique for assessing fruit nitrogen content from the same juice samples will provide even more prediction power.

Nitrogen matters in two ways, he said. First, trees with high nitrogen levels grow with more vigor, which pulls more calcium into shoots and leaves and away from the fruit where it’s needed to stabilize cell walls. Second, too much nitrogen in the fruit itself can make it more susceptible to bitter pit and other disorders.

Growing conditions play a role in bitter pit as well, so historically, risk assessment approaches developed in one region haven’t always translated well to other regions.

In 2019, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission shared results of trials comparing several prediction methods on fruit picked two weeks before harvest and found that none adequately predicted bitter pit incidence in storage.

Washington State University extension specialist Bernardita Sallato and Michigan State University extension specialist Anna Wallis said they both hope to test this peel sap method in their regions this season.

Sallato cautioned growers not to confuse this method, which uses the juice from the peel for analysis, with another form of sap analysis offered by some commercial labs looking at leaves.

The approach may need calibration to reflect Washington conditions, she said, but if that works, then researchers also need to develop guidance to help growers act on the information. By July, the fruit showing bitter pit risk is probably too late to be saved with foliar calcium applications, Sallato said, but irrigation and pruning changes might help — as might merely making more informed decisions about what to do with the block.

A piece of the puzzle

Having that bitter pit insight early is the key, according to Scott Henning, vice president of business development at Lake Ontario Fruit Inc., a Western New York packer who worked with Cornell scientists to develop the peel sap approach.

“Bitter pit can lead to some very major losses, so we need a method to predict it so we can mitigate losses and our risk in storing the fruit,” he said. “We just need to be able to evaluate fruit before the harvest date.”

Even though it may be too late for growers to avert bitter pit in fruit showing risky nutrient ratios, having that information can help them make better economic decisions about how to handle all the variables that play into what to do with the block, Henning said.

Henning also now uses the passive prediction method, which involves taking 100 fruit samples, picked three weeks before harvest, and leaving them at room temperature to look for the development of bitter pit.

When it comes to Honeycrisp, storage operators must balance the risk of both bitter pit and soft scald, but the temperature conditioning that reduces risk of soft scald exacerbates bitter pit, Watkins said in a presentation during the New York Tree Fruit Conference in February. He’s been evaluating the passive prediction approach to provide data on the risk of developing bitter pit; more data could help to identify the storage sweet spot for each lot of fruit.

Like every bitter pit method, the approach doesn’t offer a complete picture, Watkins said, and he’s still studying how other variables such as climate and use of stop-drop products can influence the outcome.

The prediction tools aren’t perfect, but it’s time to start using them, said Cornell horticulture professor Terence Robinson. As New York’s Honeycrisp crop has grown, more fruit is heading into long-term storage, raising the risk of expensive losses due to bitter pit.

Yes, the disorder is notoriously difficult to predict and variable from season to season, but Robinson believes that gathering as many relevant pieces of information as possible — crop load, tree vigor and rootstock, along with the peel sap and passive prediction approaches developed by Cornell scientists — can go a long way toward improving packouts.

“It’s time to put together what we know as a package and advise growers and packers,” Robinson said at the New York Tree Fruit Conference in February, introducing a concept he calls the Bitter Pit Passport. He hopes to assemble the relevant data for 500 Honeycrisp blocks across the state this year to help producers make decisions, while the Cornell team will evaluate how well it works.

“Whether a grower and packer decide to gamble and put that fruit in CA storage is up to them,” he said. “But if we do this year after year, that should help you get an idea of which blocks are safest.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment