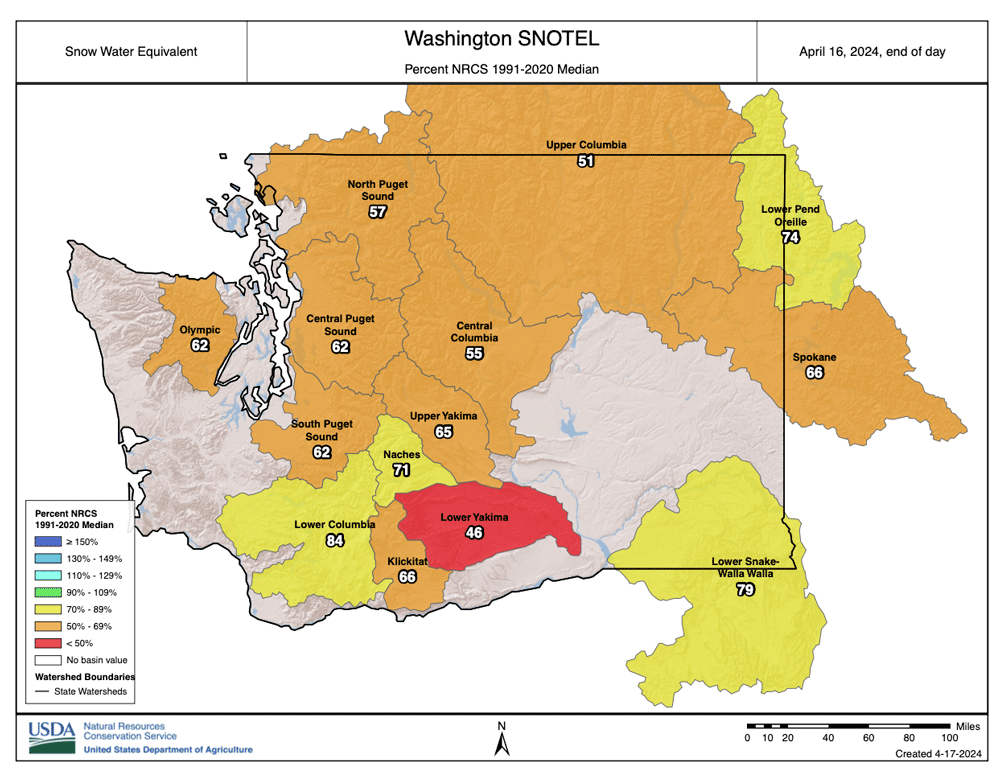

On April 16, the state of Washington declared a drought emergency for almost the entire state, citing snowpack at 68 percent of normal and warm, dry conditions in the forecast.

“There is simply not enough water contained in mountain snow and reservoirs to prevent serious impacts for water users in the months ahead,” according to a news release from the Washington State Department of Ecology.

A drought declaration opens the door for the state to offer financial assistance to respond to the drought conditions, such as helping irrigation districts lease water. A $4.5 million fund is available.

“By moving quickly to declare a drought, we can begin delivering financial support to water systems with drought impacts and work with water users to find solutions to challenges before they become a crisis,” said Laura Watson, the department’s director.

Leasing water is a critical part of the plan for the Roza Irrigation District, which serves tree fruit and wine grape growers in the Yakima Valley and has junior water rights subject to rationing during a drought. In April, the water supply forecast for the junior irrigators in the region was 63 percent, with a low-end estimate of 51 percent, said district manager Scott Revell.

Looking at the weather and the snowpack, he’s not optimistic the May estimate will be an improvement.

Revell shared how the district was preparing for a potential drought back in November in a talk presented to the Washington State Grape Society. He emphasized how the district has learned from its management of the 2015 drought, which saw just 47 percent of normal water, and invested over $20 million in water-saving infrastructure in the decade since.

Over 70 percent of the district’s acreage is in permanent crops that need water in September, so a midseason shutdown may be needed to stretch the supply. In 2015, they shut down for three weeks, but that was hard for annual crop producers, Revell said.

“If we do shut down, it will be 10 to 12 days,” he said.

The decisions will be made after the May water supply report.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment