The fruit industry uses the term “quality” all the time, but it means different things to different people.

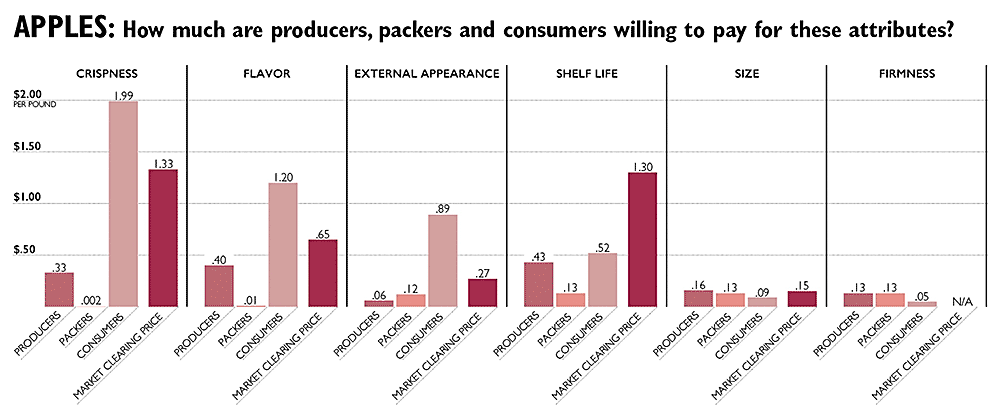

When it comes to apples, for example, shoppers value crispness, while packers think highly of, say, shelf life.

Source: Karina Gallardo, Washington State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

Karina Gallardo and some fellow economists have figured out a way to measure those variances, thus quantifying something otherwise usually dismissed as subjective.

Karina Gallardo

Through surveys of packers, growers and consumers, Gallardo, a Washington State University associate professor of economics, and a nationwide team of researchers have assigned monetary values to the importance the different groups placed on a variety of quality attributes of apples, sweet cherries, peaches, strawberries and tart cherries.

Their most surprising result — “the one that made us jump to the ceiling, the whole team,” said Gallardo at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association annual meeting in December in Wenatchee, Washington — was that the preferences of growers and consumers lined up, while the packers were the odd man out.

The end result of the project, besides just general industry education, also yielded monetary figures for each attribute for breeders to keep in mind as they develop new cultivars.

Breeders, especially those hired by universities, typically hear requests from producers and packers through advisory boards, but knowing the wishes of shoppers is important, too, since they pay the bills, said Kate Evans, WSU’s apple breeder.

“We, of course, have to take the priorities of all three into account when making selections, so it is useful to see where they converge,” said Evans, who attended Gallardo’s presentation at the annual meeting.

“Ultimately though, the willingness to pay of the consumer has to be the driving factor, as that is the only point that funds come in to the production chain.”

Methods

The survey and analysis represented a $332,000 slice of the first stage of RosBREED, the broad $7 million federal Specialty Crop Research Initiative project aimed at using genetic markers to improve breeding of new fruit cultivars.

Chengan Yue, an associate professor and Bachman Endowed Chair in horticultural marketing at the University of Minnesota, led a socioeconomics research team on the project, though Gallardo, who works at WSU’s Puyallup Extension center, supervised portions of the research.

Other collaborators were Vicki McCracken and James McFerson from WSU and James Luby from Minnesota.

The first stage of RosBREED ended in 2014. A second round expanding the genetic marker research to include disease resistance is ongoing. Gallardo’s team is part of that, too.

Likewise, Evans was and still is one of about 134 collaborators on the entire RosBREED project.

Gallardo and the team started by interviewing breeders to narrow down a long list of quality attributes to six for each type of fruit.

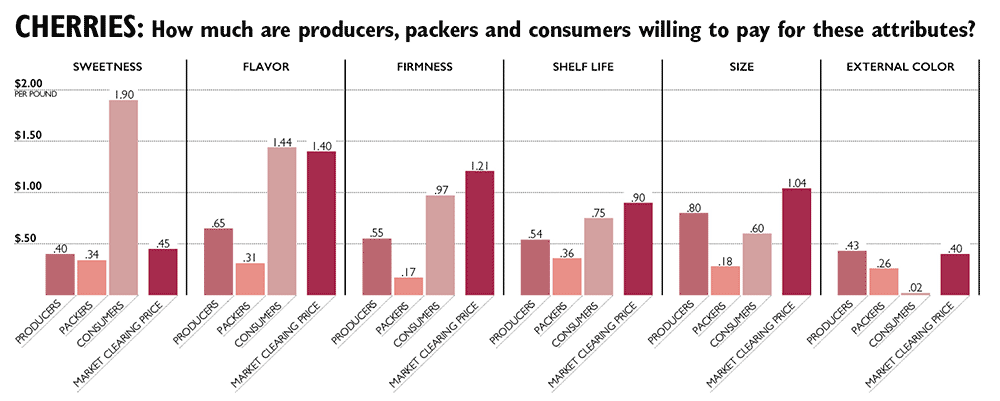

For apples, they settled on crispness, flavor, external appearance, shelf life, size and firmness. Sweet cherry attributes were sweetness, flavor, firmness, shelf life, size and external color.

Then, they sent surveys to people in three categories — packers, producers and consumers — asking them how much money they would spend to get the six different attributes in fruit.

In August 2011, they sent out mail surveys for packers, or “market intermediaries,” a category that included some marketing agencies and brokers. Forty of the 146 apple surveys were returned from nine states, a response rate of 27 percent. For cherries, 33 of 97 surveys — or 34 percent — were returned from five states.

The producers, or growers, were surveyed by mail in June 2012, with 321 out of 1,000 surveyed about apples responding from five states, for a 32 percent rate. For cherry growers, 215 of 648, or 33 percent, responded from five states.

The researchers surveyed consumers in October 2013 nationally through online surveys, through a research company named Qualatrics, which delivered 1,000 completed responses from shoppers who purchased the fresh fruits in question within the past three months. The contract with Qualtrics called for a demographic mix of ages, gender, ethnic background and geography representative of the population.

Results

Source: Karina Gallardo, Washington State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

As for that magic number for the breeders, Gallardo calls it the “market clearing price,” the point at which the consumer’s willingness to pay for an attribute in the checkout line intersects with the grower’s willingness to pay to grow fruit with that attribute.

“That’s the money number,” Gallardo said.

With apple crispness, for example, that figure is $1.33 per pound. She and her team compared only grower and consumer survey responses for the market clearing prices.

Meanwhile, the researchers were surprised at how well growers and consumers spoke the same language of quality. “Producers are getting to understand consumers, so that’s great,” Gallardo said.

For apples, for example, consumers said they would spend the most money, $1.99 per pound, on crispness, followed by flavor and external appearance.

Growers shared crispness and flavor in their top three, while packers said they would invest the most for shelf life, size and firmness.

Growers and consumers also lined up on cherry quality priorities compared to packers, but to a lesser extent.

Gallardo speculated packers simply have a broader array of responsibilities than growers, such as shipping efficiency and grade inspectors, and therefore may be less willing to spend money on attributes such as flavor.

Naches, Washington, grower Morgan Rowe had a similar guess.

“Maybe it’s the fact that a grower and consumer are more alike,” said Rowe, who does not pack or ship fruit. “They appreciate the same attributes, specifically eating. A packer does, too, but (packers) have to receive the fruit, store it, run it, and box/ship it. So there are possibly different concerns to worry about.”

Packers appear to have selected the attributes that directly affect their reputation and efficiency, said Tim Welsh, general manager of new variety and orchard development for Columbia Fruit Packers in Wenatchee.

“(The) grower pays all cost of repack, but packer/shippers do not make money on repacked fruit and suffer consequences like a stinging rebuke when fruit is rejected at delivery,” he said.

Welsh and Rowe did not attend Gallardo’s presentation, but commented after the Good Fruit Grower shared some of her research results with them.

Gallardo shared only results for apples and sweet cherries at the conference. Her team is still crunching numbers for peaches. Also, because many packers also own orchards, the team collected data about such packers, but not enough to parse out any conclusions about them, she said.

Portions of their research have been published in the journals HortScience, Agribusiness, Agricultural Resources and Economics Review and International Food and Agribusiness Management Review. •

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment