For the record—since this could be an event of historic significance—the harvest took place about two o’clock on the afternoon of July 11 in the orchard of Ed and Phyllis Oxley and their son, Chris, near Marcellus, Michigan.

In 12 minutes, the Korvan 9000 Vertirotor, with Chris at the helm, gathered two-thirds of a tank of cherries, clean and undamaged, from two rows with 180 trees. The trees were small, the crop was light, and hail damage made the fruit unsuitable for normal pitting and processing, Oxley said. Instead, the cherries went to a winery that makes cherry wine.

The machine traveled at 1.3 miles per hour, the shaker frequency was set at 850 vibrations per minute, and the ethephon-treated cherries were removed with a pull force of 180 grams. The significance of all this becomes clear when one realizes how far from “normal” this process was.

Michigan State University horticulturist Dr. Ron Perry was there to explain it to the 20 or so people who came to watch the harvest.

Mechanical harvest

by Richard Lehnert

Tart cherry harvest was mechanized more than 50 years ago, first with limb shakers, later with trunk shakers. Since then, tart cherry trees have typically been grown on a spacing of about 19 feet square.

They are harvested with trunk shakers and inclined-plane catching frames. To get a trunk robust enough to be shaken takes six years, during which time no fruit is harvested. The trees grow tall, sitting atop four-foot-high trunks, and it takes a lot of alley space to move the shakers, catching frames, conveyors, and water-filled receiving tanks.

Waiting six years for first fruit doesn’t make economic sense, Perry said, especially since trunk shaking damages trees and shortens the life of orchards. The productive life of tart cherry orchards is clipped at both ends.

Supported by Michigan’s cherry producers and Michigan State University’s Project GREEEN, Perry began looking at alternatives in 2008 with initial trials conducted on tart cherry seedlings in Dr. Amy Iezzoni’s tart cherry breeding program.

He had also been following work in Poland on that country’s smaller Schattenmorelle tart cherry trees, on which researchers had been trying over-the-row harvesters since 1994.

Then, in 2011, Perry and a team of MSU researchers established a trial for over-the-row harvesting at the Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center in Traverse City, using trees that included naturally compact varieties as well as Montmorency, and also pruning and training treatments.

The trial included varieties from the breeding programs of Iezzoni and Dr. Bob Bors at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, who had already been doing work with dwarf tart cherries and machine harvest.

In the cold environment of Saskatchewan, Bors found that bush-like cherries survived the hard winters better and could be harvested with equipment already in use to harvest haskaps (honeyberries) and saskastoons. Adding cherries would expand the use of the machine into a new season.

In 2008, Perry set up a machine harvesting demonstration using a blueberry harvester on an experimental orchard that Iezzoni developed. The orchard contained trees of all sizes and varying genetics, so it was a good way to test a new concept and see how the trees responded to it.

“Lucky” hailstorm

In April of 2010, a severe hailstorm devastated 50 acres of young tart cherries that grower Ed Oxley had planted. He sought advice from local extension educator Mark Longstroth, who contacted Perry.

Oxley, who was very familiar with over-the-row harvesting because he used it for his juice grapes, was interested in trying a grand experiment. He had been following the MSU research team and observing their preliminary trials conducted in 2009 and 2010.

He decided to restart 20 acres of those three-year-old hail-damaged trees by heading the trunks back to 18 inches high and letting new limbs develop.

Some trees developed multiple trunks and are bush-like; others have single leaders, but all are bushy looking, with branches originated at 12 to 18 inches.

The next spring, in 2011, Oxley interplanted two new trees between each of the old ones, converting the orchard to a 6- by 19-foot planting. “The goal was to develop bush-form trees in a hedge pattern,” Perry said. The new trees were special-ordered, since nurseries routinely remove lower branches from young tart cherry trees, and he and Oxley didn’t want that done.

Both Oxley and Perry seemed quite sure the new orchard could be harvested with a blueberry harvester.

“We’re concerned now about keeping these trees under control,” Perry said. The trees were planted on traditional Mahaleb rootstocks, so they have the capacity to grow large.

More experiments

Working with Michigan State University horticulturist Dr. Jim Flore, they devised pruning experiments in Oxley’s new orchard. Using a hedger, they narrowed the canopies to three feet and five feet thick in two tests.

In a third, they hedged and topped to remove half of all new growth. In one, they removed half the new growth in the top only. And in a fifth, they employed renewal pruning techniques, in which large branches are cut back to 8- to 10-inch stubs to generate new, smaller growth and discourage development of permanent scaffold branches.

Flore conducted hedging research on traditional large trees more than 20 years ago at MSU and believes that hedging away new growth will not only narrow the tree but will stimulate new flower buds. Flower buds for the next year’s crop form about mid-June, so they hedged 45 days after bloom.

MSU agricultural engineer Dr. Dan Guyer is evaluating technical aspects of the tree-machine interactions and fruit quality. He thinks using the new harvester will improve quality because it will require less fruit removal force, do less tearing where fruit is removed from the stems, and greatly reduce the accelerated speed at which cherries end their trip from tree top to catching surface. Cherries now fall 20 and more feet, through a canopy, on their way to a catching frame.

The throat of the Korvan harvester is five feet wide and eight feet tall, so the maximum fall to the folding fish-scale plates is eight feet.

“This potentially revolutionary production concept, which is developing under synergistic horticultural and mechanical optimization simultaneously, addresses multiple issues within the cherry industry from trunk damage, fruit damage associated with tall drops, spray containment, and overall economic returns over the life of an orchard,” Guyer said.

Ken Engle, a cherry grower from Traverse City, 200 miles north of Oxley, came to see the harvest because he’s planted new orchards in the hedgerow manner and plans to harvest over the row in about two years. He carried double handfuls of the fruit, admiring the lack of damage. He, like Guyer, thinks fruit quality will be better with this new method.

Roger Bell, an engineer from Oxbow (which owns the Korvan brand), said the machine is quite adjustable for both shake frequency and amplitude.

The shaking action is transmitted to 750 fiberglass tines on a spindle that turns as the tree moves through the harvester throat. The tines reach into the tree, and the shaking is done inside the canopy, rather than from a trunk movement that whips the upper branches.

“The harvester is working efficiently even without any changes in components on the blueberry harvester,” Perry said.

It is virtually unmodified from its blueberry harvest design. Engineers, of course, love to torch new machines and make them better. They were already contemplating conveyors to move cherries into more conveniently located bins for faster bin changing. And Chris Oxley wants to go faster. “I spray at 15 miles per hour,” he quipped.

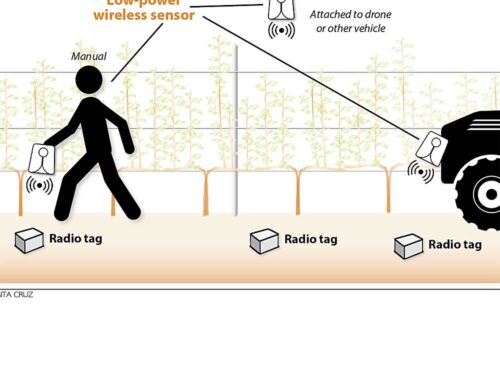

[…] To address this issue, alternative methods, such as the use of precocious dwarfing rootstocks and over-the-row harvesting systems, are being explored for both young orchards and high-density […]