All in all, the cherry industry performed well in 2020 amid challenges and rapidly changing market dynamics, many of which likely will continue this year.

That was the message from marketing officials at the 78th annual Cherry Institute, held virtually on Jan. 21. Northwest Cherry Growers, the Yakima, Washington-based organization that collectively markets sweet cherries for the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Utah, combined its winter event with Washington State University’s annual Northwest Stone Fruit Day, as a series of webinars.

Shopping habits altered by the coronavirus pandemic, loss of acreage due to little cherry disease and bad early season weather threw the industry some curveballs in 2020, but growers produced large, quality fruit and demand went through the roof, said B.J. Thurlby, president of Northwest Cherries.

“I would say that the demand from start to finish was the strongest we’ve seen in the past decade,” Thurlby said.

Meanwhile, 84 percent of Northwest cherries shipped in 2020 were 10.5 row size or larger, tied for the 2016 record.

“It just tells the story that the growers did an excellent job growing the fruit this year,” Thurlby said.

Volume wise, 2020 was average, he said. Northwest companies shipped 19.8 million 20-pound equivalent boxes. The largest volume was 26.4 million in 2017. California’s crop came in at roughly average with 5.9 million equivalents, giving the Pacific Coast a 25.7 million box haul.

“Kind of a normal-sized crop,” Thurlby called it.

Acreage removed due to X disease and little cherry disease caused up to a 2.5-million-box dip in volume, Thurlby said.

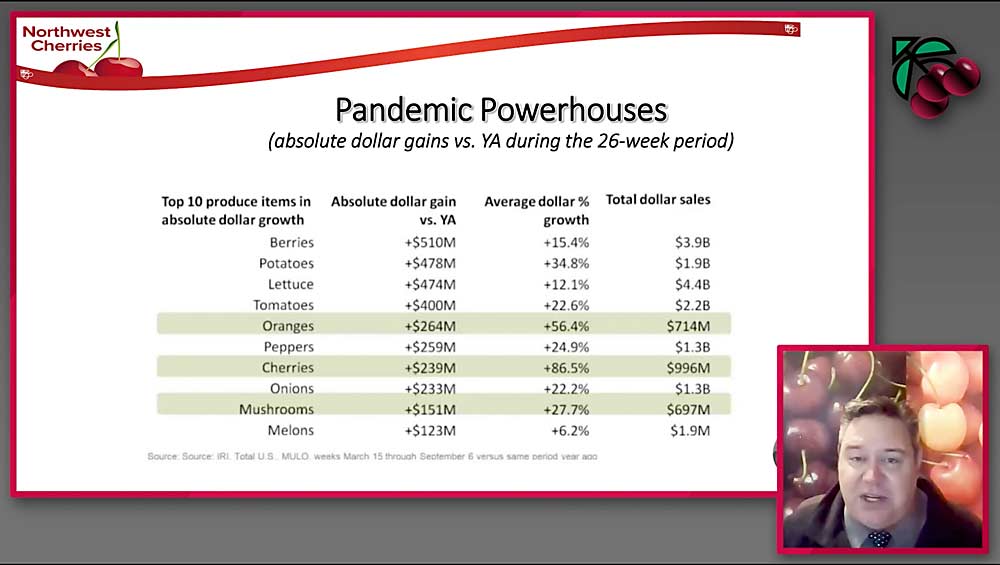

Meanwhile, as the coronavirus closed restaurants and made meetings with retailers more difficult, shoppers flocked to produce, whether online or in stores, especially cherries, said Thurlby and James Michael, Northwest Cherries’ vice president of marketing for North America.

Online grocery store sales jumped 500 percent between August 2019 and June 2020, so Michael and his marketing colleague pivoted to convince retailers to use cherries prominently in online advertising. Costco posted cooking videos using cherries to help replace their well-known store demos. Other stores shared videos of dieticians discussing cherry health benefits.

Walmart handed out 405,000 free sample bags to curbside pickup customers and reported an increase of 425 percent in online red cherry sales and 700 percent in blush cherries.

In Northwest Cherries’ surveys, 39 percent of shoppers said they learned about cherries from online promotions, compared to 30 percent who simply saw them in stores — which had long been one of the most impactful ways to market cherries.

A total of 42 percent of cherry buyers purchased cherries online last year, while 10 percent only used online shopping for cherries.

Meanwhile, the industry’s long-running health messages seemed to gain more traction with shoppers this year, Michael said; 59 percent of survey respondents cited health concerns as a factor in their cherry purchases.

Michael expects many of the shopping trends — online sales and health motives — to continue in 2021.

Little cherry focus

The meeting’s morning session focused on management of X phytoplasma and little cherry virus, the two pathogens that result in small, distasteful fruit.

Often lumped together under the umbrella term “little cherry disease,” since the pathogens cause similar symptoms and require similar strategies for control — scout for symptoms, get trees tested and remove infected trees — it’s X disease that’s the primary threat to Northwest growers at the moment, said Scott Harper, a pathologist at Washington State University.

The phytoplasma with causes X disease is vectored by leafhoppers that tend to proliferate in orchards after harvest, feeding on both broad leaf weeds and trees. WSU entomologists Tobin Northfield and Louis Nottingham shared their findings on insecticide efficacy and deterrents such as kaolin clay on the trees or using reflective mulch to cover the orchard floor.

To monitor for leafhoppers, Northfield recommended growers set up sticky traps relatively low in the canopy, because they are coming from the groundcover.

“Right now, we are focused on presence,” he said in response to a question about trap thresholds. “Bottom line: If they are there, you should be treating.”

Tianna DuPont with WSU extension shared findings about the best strategies for tree removal, including how and when to use herbicides to check whether the pathogens could be spreading via root-grafting.

For more on X disease and little cherry disease, see upcoming stories in Good Fruit Grower’s Feb. 15 issue on disease management and March 1 pest management issue.

Other webinars include a presentation on using blue orchard bees for cherry pollination, the latest research on cherry orchard systems, the biology for flowering and fruit set, cold damage mitigation, and managing the emerging fungicide resistance in cherry powdery mildew. All the presentations are available to watch on demand at http://treefruit.wsu.edu/article/cherry-institute-2021-presentations/

—by Ross Courtney and Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment