Mike Omeg reminds growers not to get too hung up on the specifics.

Photo by Geraldine Warner

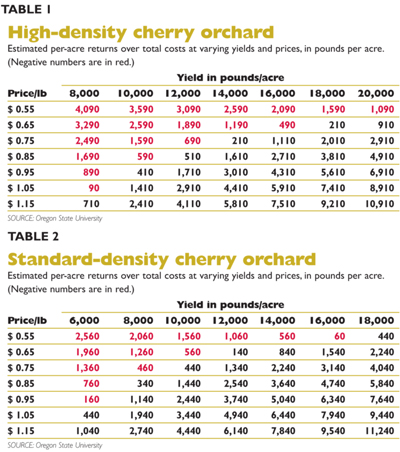

Oregon State University agricultural economists recently updated enterprise budgets for both standard and high-density sweet cherry orchard systems. Enterprise budgets are designed to help growers estimate actual costs and review individual production costs against industry averages.

The budgets are developed from analyzing the costs of typical orchard practices shared by a participating team of growers. The individual costs are then averaged to estimate per-acre costs associated with the particular crop or orchard system under study. Budgets are a guide and not meant to be representative of any particular farm.

The two updated enterprise budgets reflect the typical costs associated with standard and high-density, fresh-market sweet cherry production in Wasco County, Oregon. Authors of the reports are OSU’s agricultural economist Clark Seavert, instructor Rebecca Sullivan, student Tyler West, and extension horticulturist Lynn Long.

For the standard-density orchard, the budget is based on 60 acres (with 136 trees per acre) on Mazzard rootstock, planted on a spacing of 16 by 20 feet. Trees are mature, 15 to 25 years old, with establishment costs fully amortized prior to the budget. Production is 12,000 pounds (6 tons) per acre, at a gross price to the grower of 85 cents per pound.

The high-density orchard budget is based on 25 acres with 340 trees per acre on Gisela 6 rootstocks and planted on a 10- by 16-foot spacing. The trees range in age from 8 to 15 years with establishment costs amortized over a 25-year period. Average production is 14,000 pounds (7 tons) per acre at a gross price to the grower of $0.85 per pound.

Cherry grower Mike Omeg of The Dalles, Oregon, who’s provided data in previous enterprise budgets, reminds growers not to get too hung up on the specifics. He explains that it’s difficult to compile a set of figures reflecting the diversity of individual production practices that are followed by growers.

For example, some growers put a lot of effort and cost up-front in planting and training orchards, while others less so. “That’s always been the criticism of enterprise budgets—how to balance different management styles and practices of the growers providing the data,” he said.

In the latest cherry enterprise budgets, Omeg thinks the average production of six tons used in the standard-density enterprise budget is on the “high” side. “Most standard-density blocks in The Dalles are less than six tons,” he said, noting that the countywide average is around four tons.

Also, he believes the seven-ton average for high-density blocks is on the low side and that most high-density orchards are yielding higher than 14,000 pounds per acre.

Additionally, he has not found input costs to be much different between his family’s standard-density and high-density orchard systems. The OSU enterprise budgets showed about $685 per acre more in variable cash costs for the high-density system compared to the standard, but $600 of that was higher harvest costs because of the higher tonnage picked (12,000 pounds versus 14,000 pounds).

When looking at the costs involved in producing a pound of fruit, the higher density system was more efficient, with fruit costing $0.50 per pound to produce compared to $0.53 for standard density.

Price, production, labor costs

Price, production, labor costs

What Omeg zeroes in on when reviewing an enterprise budget are price, production, and labor costs. He pays particular attention to harvest costs.

“I look at the production

Omeg says he tends to spend more per acre on inputs than those shown in the enterprise budgets. “Sometimes I spend twice as much on pruning as the enterprise budget, but then I might receive 15 cents more per pound for my fruit than the budget’s.”

During harvest, he pays close attention to harvest management and labor costs because slight changes—up or down—can have a substantial impact on the bottom line. “If workers are shorting fruit in the buckets by two pounds, the financial impact can be substantial over the course of the season. If the workers can pick faster and bring in more fruit per picker because of the orchard system—like we’ve seen in high-density plantings—that makes a big difference in spreading out labor overhead over more pounds of fruit picked.”

Minimizer or maximizer?

“I heard Clark Seavert say once there are two ways to approach farming. Growers can be cost minimizers, looking for ways to reduce their costs, or they can be profit maximizers and seek ways to increase their profit,” Omeg said. He believes that most growers are cost minimizers, and approach a budget by looking for places to shave off their input costs. “In the past, growers have done really well with that approach.”

But he describes himself as a profit maximizer. “I’m willing to spend more per acre for things like pruning and such if it will make $800 more in fruit.” However, he admits that risk is greater for profit maximizers if there’s a problem, say rain at harvest, because more resources are exposed.

Omeg likens his focus on price, production, and labor to sitting on a three-legged stool. “If any one of the legs is off kilter, then you fall off the stool.” He finds the enterprise budgets valuable in comparing his input costs to industry averages and identifying orchard practices that warrant further review to understand why costs are above or below industry averages.

Leave A Comment