Wherever there is wood, you can find wood-rotting fungi.

A wide range of relatively weak, wood-decaying fungi can cause cankers and dieback over time in stone fruit. They’re often referred to by genus — Eutypa, Cytospora, Calosphaeria, Botryosphaeria — and not to be confused with bacterial canker caused, not surprisingly, by bacterial infection.

Recently, scouts have seen more signs of these fungal canker pathogens in some Washington stone fruit orchards, sightings that raise questions about which pathogens are causing the dieback and what growers can do about it.

“Most likely, we’re seeing this because we are scouting so much more in cherry blocks,” said Garrett Bishop of G.S. Long Co. “We had some (weak) young trees and were trying to figure out what was going on.”

To be clear, the symptoms Bishop saw — leaders dying back, decaying wood revealed when branches were cut back — were not widespread or spreading rapidly. “It’s not like fire blight,” he said. But cutting out the damage does cost growers production.

“Most of the fungi that cause cankers are relatively weak pathogens,” said Gary Grove, a Washington State University pathologist who last studied such canker-causing fungi in the early 2000s, before returning his attention to the much more pressing challenge of powdery mildew.

He recalls outbreaks of cytospora canker following droughts and deep freeze events over his nearly 40 years at WSU. But other stresses, from climate to dwarfing rootstocks to other diseases, could create new opportunities for these typically secondary pathogens.

Most of the local research was done back in the 1990s, Grove said, and things change.

“Our industry has changed, our climate has changed, varieties have changed, cultural practices have changed,” he said. “We need to go back and take a second look.”

The Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission agreed, funding Grove to work with Bishop to start collecting pathogen samples from orchards in Washington and Oregon this season. Grove will culture and identify the pathogens he finds, then catalogue the samples for further study.

Prescribing control practices depends on better understanding which pathogens are driving symptoms, he said. While Bishop sent samples to a lab that uses DNA marker tests to identify pathogens, and found many symptomatic samples tested positive for Eutypa species, Grove believes it may be more complicated.

“I grew up in Ohio, lived in a house my parents built — until 1972. If there was a murder in that house right now, they could probably still detect my DNA there. Doesn’t mean I committed the crime,” Grove said. Similarly, DNA marker tests — at this stage — can’t tell the full story.

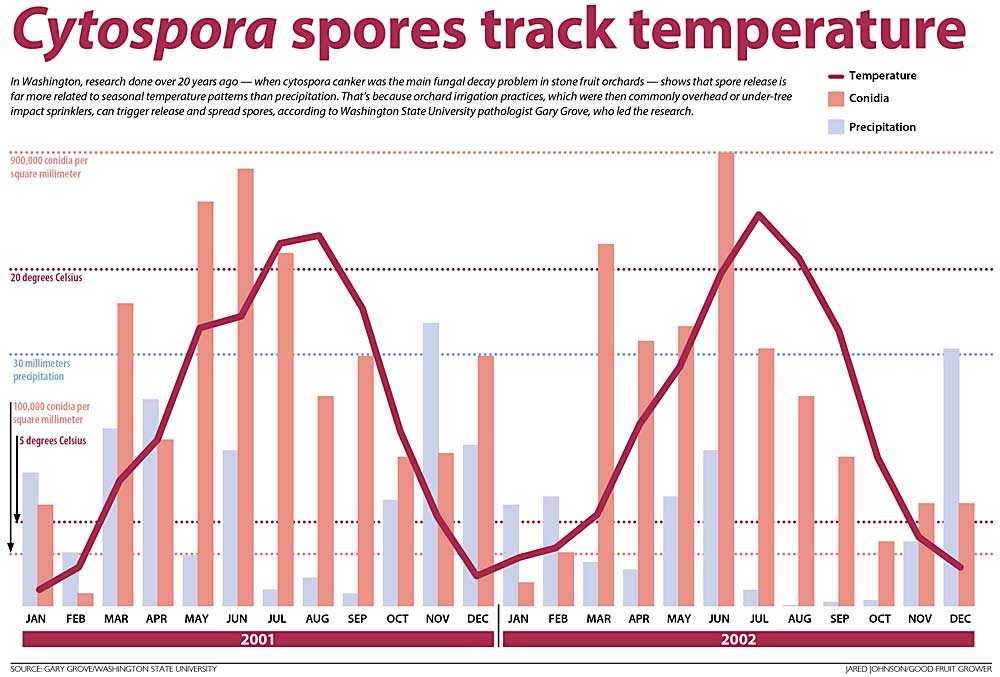

Thirty years ago, surveys found that Cytospora species were the most common canker-causing fungi in Washington’s peach and cherry orchards, Grove said. Research from California suggested the highest risk for infection would be in the wet winter season, but when Grove and his colleagues set out spore traps, they found the highest pressure in the summer.

In research on cytospora canker, specifically, he found that irrigation water from overhead and under-tree impact sprinklers effectively spread the spores, also called conidia. That finding in the early 2000s bolstered growers switching to microsprinklers or lowering the angle of their under-tree sprinklers to avoid splashing spores into a canopy with vulnerable pruning wounds.

Grove said no one in the region had studied the impact of irrigation for Eutypa species, but that will likely be an important piece of the puzzle as well.

“This is a very arid area, and these canker fungi require water. They don’t care whether it comes from a pipe or a cloud,” he said. “That’s the biggest thing — our irrigation is going to affect it.”

In March, Bishop organized a meeting and invited researchers from California, where there’s been more recent research into these pathogens, to address a Washington audience.

Almost all the participants who responded to a survey said they had experience with one or another type of fungal canker disease, considered it a cause of economic impact and supported further research on the topic.

During the meeting, Florent Trouillas, a pathologist with University of California, Davis, based at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center, shared insights from a recent project examining the seasonal susceptibility of pruning wounds in sweet cherry with three common pathogens: Calosphaeria pulchella, Cytospora sorbicola and Eutypa lata. Trees affected by all three show branch dieback as the fungal growth in the woody tissue stops sap flow, he said.

He found that for Calosphaeria, pruning in the winter, when temperatures were too cold for spore germination, was highly protective. But for Eutypa and Cytospora, California’s winter temperatures did not halt spore production. Washington’s winters may be a whole different story, however.

His studies, funded by the California Cherry Board, also show that pruning wounds are the primary pathway to infection for all three species, but fruit scars created during harvest can also be an entry point.

He recommends growers watch the weather forecast before pruning.

“Before we think temperature, we want to think rain. If there is a two-week forecast of no rain, then prune,” he said.

While Trouillas’s work shows some fungicides, such as Topsin M (thiophanate-methyl), protect against Cytospora and Eutypa infections, the logistics of spraying these products right after pruning, when branches litter the block, is a challenge, Bishop said. Moreover, Topsin M is not yet labeled for this use in Washington orchards.

The planned survey should boost understanding of which species are driving symptoms and help to identify disease pressure peaks and effective protective practices.

Until then, Bishop suspects that the timing of pruning matters. Pruning during Washington’s winters, when few fungal spores are active, is probably protective, even though the pruning wounds take longer to heal. The risk likely increases when growers stretch the work into spring, when it’s warmer and rainier.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment