It’s easy to get overwhelmed with the plant growth regulator options on the market, but when it comes to improving cherry fruit quality, gibberellic acid (GA3) ticks all the boxes: size, firmness, defect reduction, uniform color and maturity, good stem condition and taste.

Byron Phillips, a crop consultant with Valent USA, offered tips on best practices for using the hormone, also known as Gibberellin A3, in cherries at the Cherry Fruit School, hosted by Washington State University and Oregon State University in March.

Gibberellins are a group of plant hormones that influence a wide variety of development processes, including shoot growth, flower development and senescence. GA3 plays a particular role in cell expansion, division, ripening, flowering and cell wall strength, which is what matters most to cherry growers, Phillips said.

While the most powerful plant growth regulators available to cherry growers remain chain saws and loppers, he said, GA3 can be used to delay maturity as a harvest management tool and shows an increase in fruit quality metrics of firmness, size, soluble solids, luster, stem color and storage life.

“GA is not a substitute for good farming and harvesting practices,” he said. “It’s a cherry on top, but you’ve got to do those things right.”

Using plant growth regulators is an art as well as a science, since their effect is influenced by cultivar, vigor, crop load, environmental conditions, timing, rate and coverage. Self-fertile cultivars tend to need higher doses and may benefit from split applications.

There are some downsides, including somewhat increased susceptibility to rain splits, Phillips said, especially if the rain happens in the few days after application. It also seems to increase the severity of those splits.

Expect repercussions if you overapply, however.

“You can reduce or delay red blush on blonde cherries if you overdose,” he said. “I’ve seen very severe cases of overdosing; we’ve created blind wood, we’ve killed off the fruiting wood in lateral branches.”

It can also reduce return bloom, especially on young fruiting wood, which actually could be a benefit in some cases.

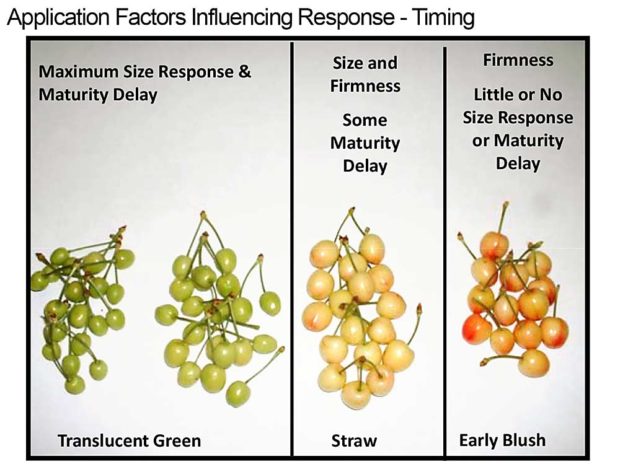

The response you get depends on the timing of application and the rate. Phillips recommended spraying at the end of the pit hardening phase, before the rapid period of fruit cell enlargement that follows.

“That’s really critical to understand that pit hardening is a process that happens over a two- to three-week period. It’s not a finite time,” he said. Straw color is sometimes used as an indicator, but it’s not accurate for all varieties, so he recommends the knife approach. “When you can’t slice through a cherry pit without cutting your thumb off, that’s the end of pit hardening.”

Apply too early, and it won’t have any effect. Apply late and it might have some positive effect on firmness, but that’s it, so Phillips doesn’t recommend it. Splitting applications can be helpful for some varieties, such as Chelans, which have a staggered bloom and uneven maturity.

The dosing — in rate per acre, not parts per million — depends on the variety and the crop load. Lightly cropped trees show the best response, but also run the risk of overdosing. Overcropped trees, on the other hand, likely show little response.

“There’s no magic answer,” Phillips said. “So, for example, if you’ve got Bing on Mazzard, looking at 4 to 5 tons per acre, that’s when I look at 16 grams per acre. If you have a really heavy crop load and you are pushing 10 tons per acre on Bing, you’re looking at 32 grams per acre.”

To get a consistent response, good coverage is critical, and Phillips recommends slowing down the sprayer to 2 mph or less. In older systems, full dilute sprays at 400 gallons per acre get the best coverage but minimize risk; in newer, higher-density plantings, growers can spray at 80 to 200 gallons per acre, but this does increase the risk of overdose impacts and decreasing return bloom.

Coverage matters because studies have shown that on big, open-vase tree canopies, only about 10 percent of any PGR applied makes it to the intended destination on the cellular level, he said, and GA3 has even worse odds.

“For something like GA, where the target is the fruit, and there’s no translation in the tree, that number is closer to 4 percent,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons coverage is tremendously critical.”

Applying GA3 tank-mixed with calcium shows added firmness benefits, since calcium plays an important role in cell wall structure, but that’s also shown to limit fruit size somewhat. Surfactants can help with coverage and absorption — but never use a silicone surfactant with GA3, Phillips said.

The optimum temperature for absorption is around 80 degrees Fahrenheit, but anywhere from 60 to 90 degrees will work. Spraying at night is actually a mistake, he said. Hot, windy growing conditions that stress trees will also reduce the response, compared to cool growing seasons that delay maturation.

“I get a lot of questions about rain, but if you’ve got two hours of drying time, you’ve got enough absorption to do what you need to do,” he said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment